The Senate had a hearing that I missed.. here is a link to the testimony. Anyone watch it and have observations?

Fire and Fuels

Closure and Rehabilitation of Temporary Roads

Here is a view of a temporary road used in a fire salvage portion of a green timber sale, on the Sequoia National Forest. The McNally Fire burned over 100,000 acres. Since this location is so remote, worries about vehicular entry are minimal. At the time, the logger and I thought these rocks would be adequate to block the road. I don’t think so, today. This was a temporary road before the fire, and there were some hydrological issues with re-using it. Of course, after a wildfire, the water table is recharged and new springs have popped up. It was very important that we laid out the restrictions and mitigations of its use. This is the result.

This view looks back down the road. You can see the waterbars and slash spread in between them. Even if the road is compacted, the water never gets a chance to gain erosive power. I’d bet that the road could be re-used again, when needed. The original road design wasn’t perfect but, I think there are very few impacts from us using it.

Forest Red Zone Report.. Link to Bob Berwyn Post

Bob Berwyn has a nice post on the new Red Zone Report.

Here is a link to his post.

Below is an excerpt.

Here is a link to the report. It is a GTR from the Rocky Mountain Research Station.

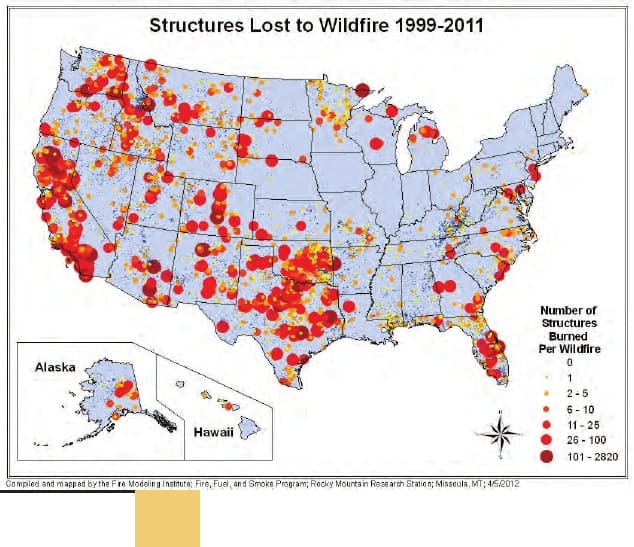

According to the report, about 32 percent of U.S. housing units and 10 percent of all land with housing are the wildland-urban interface. The growth of residential zones around fire-prone forests has resulted in huge budget challenges for the Forest Service. Between 2001 and 2010, fire suppression costs doubled to about $1.2 billion. Read the full report here.

Other costs include restoration, lost tax and business revenues, property damage and costs to human health and lives. As and example, the report cites the 1996 Buffalo Creek Fire, which resulted in more than $2 million in flood damage and $20 million in damage to Denver Water’s supply system.

From the report:

In 2000, nearly a third of U.S. homes (37 million) were located in the WUI.

More than two-thirds of all land in Connecticut is identified as WUI.

California has more homes in WUI than any other State—3.8 million.

Between 1990 and 2000, more than 1 million homes were added to WUI in California, Oregon, and Washington combined.

WUI is especially prevalent in areas with natural amenities, such as the northern Great Lakes, the Missouri Ozarks, and northern Georgia.

In the Rocky Mountains and the Southwest, virtually every urban area has a large ring of WUI, as a result of persistent population growth in the region that has generated medium and low-density housing in low- elevation forested areas.“The Wildfire, Wildlands and People report reminds us that people can and should take steps to protect their homes from wildfires,” said U.S. Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell. “Communities with robust wildfire prevention programs are likely to have fewer human-caused wildfires. In addition, fire intensity is dramatically reduced in areas where restoration work has occurred.”

Between 2006 and 2011, some 600 assessments were completed on wildfires that burned into areas where restoration work had taken place. In most of these cases, fire intensity was reduced dramatically in treated areas. Residents can reduce excess vegetation within and around a community to reduce the intensity and growth of future fires and create a relatively safe place for firefighters to work to contain a wildfire, should one occur.

Spruce Beetle- Beetle Without Drama and With FS Research

One thing I noticed when panels of scientists came to talk to us about our bark beetle response (from CU particularly) is that they kept talking about our “going into the backcountry and doing fuel treatments” and why this was a bad idea. We would tell them we weren’t actually doing that, but I don’t think they believed us. I have found in general, that people at universities tend to think that a great deal more management is possible on the landscape than actually ever happens. The fact that Colorado has few sawmills means we aren’t cutting many trees for wood..

Anyway, in my efforts to convey this “there isn’t much we really can/can afford to do in these places”, I ran across this story.. It just seems so common-sensical and drama free. Perhaps that is the culture of the San Luis Valley, reflected in its press coverage.

Note: Dan Dallas, the Forest Supervisor of the Rio Grande National Forests (and former Manager of the San Luis Valley Public Lands Center, a joint FS/BLM operation, ended for unclear reasons) is a fire guy, so has practitioner knowledge of fires, fire behavior and suppression.

A beetle epidemic in the forest will have ramifications for generations to come.

Addressing the Rio Grande Roundtable on Tuesday, Rio Grande National Forest staff including Forest Supervisor Dan Dallas talked about how the current spruce beetle epidemic is affecting the forest presently and how it could potentially affect the landscape and watershed in the future. They also talked about what the Forest Service and other agencies are doing about the problem.

We’ve got a large scale outbreak that we haven’t seen at this scale ever, Dallas said.

SLV Interagency Fire Management Officer Jim Jaminet added the infestation and disease outbreak in the entire forest is pretty significant with at least 70 percent of the spruce either dead or dying “just oceans of dead standing naked canopy, just skeletons standing out there.”

Dallas said unless something changes, and he and his staff do not think it will, all the spruce will be dead in a few years.

As far as effects on wildlife, Dallas said the elk and deer would probably do fine, but this would have a huge impact on the lynx habitat.

He also expected impacts on the Rio Grande watershed all the way down to the New Mexico line. For example, the snowpack runoff would peak earlier.

However, Dallas added, “All that said, it is a natural event.”

He said the beetle epidemic destroying the Rio Grande National Forest spread significantly in just a few years. He attributed the epidemic to a combination of factors including “blow down” of trees where the beetles concentrated on the downed trees, as well as drought stressing the trees so they were more susceptible to the bugs, which are always present in the forest but because of triggering factors like drought have really taken over in recent years.

“There’s places up there now where every tree across the board is gone, dead,” Dallas said. “It’s gone clear up to timberline.”

He said the beetle infestation could be seen all the way up the Rocky Mountain range into Canada.

Safety first

To date, the U.S. Forest Service’s response has focused on health and safety both of the public and staff, Dallas explained. Trees have been taken out of areas like Big Meadows and Trujillo Meadows campgrounds where they could pose a danger to visitors, for example.

“Everybody hiking or whatever needs to be aware of this. All your old habitats, camping out underneath dead trees, that’s bad business,” Dallas said.

He said trail crews can hardly keep up with the debris, and by the time they have cleaned up a trail, they have to clear it again on their way back out.

Another way the Forest Service is responding to the beetle epidemic is through large-scale planning, Dallas added.

For example, the Forest Service has 10 years worth of timber sales ready to go at any point in time, which was unheard of a few years ago.

……….

Forest research

Dallas said a group of researchers from the Forest Service will be looking at different scenarios for the forest such as what might happen if the Forest Service does nothing and lets nature take its course or what might happen if some intervention occurs like starting a fire in the heat of summer on purpose.

The researchers are expected to visit the upper Rio Grande on June 17. They are compiling a synthesis before their trip. They will then undertake some modeling exercises to look at what might happen in the forest and what it will look like under different scenarios.

“We have the opportunity now to do some things to change the trajectory of the forest that comes back,” Dallas said. “We want to understand that, not to say that’s something we really want to do.”

He added, “We would have to involve the public, because we are talking about what the forest is going to look like when we are long dead and gone and our kids are long dead and gone.”

If the Forest Service is going to do something, however, now is the time, he added.

Fire risks

Jaminet talked with the roundtable members about fire risks in the forest.

Fire danger depends on the weather and the environment, he said.

If the conditions were such that the weather was hot, dry and windy, “We could have a large fire event in the San Luis Valley,” Jaminet said.

He added that fortunately the Valley does not have many human-caused fires in the forests. The Valley is also fortunate not to have many lightning-caused fires, he added.

“Will there be an increase in fires?” he asked. “Probably not. Will there be an increase in severity? Probably not now but probably later. The fire events are going to be largely weather driven.”

He said some fire could be good for an ecosystem as long as it does not threaten structures and people

One has to wonder whether the reviewers of the NSF studies (in this post) knew that the FS was doing what appears to be addressing the same problem, only with different tools. Seems to me like some folks who study the past, assume that the past is somehow relevant to the best way forward today. I am not against the study of history, but, to use a farming analogy, we don’t need to review the history of the Great Plains before every planting season.

Maybe there should be financial incentives for those who find duplicative research, with a percentage of the savings targeted for National Forest and BLM recreation programs ;)?

Wisconsin wildfire started by logging operations destroys 17 homes

From the Associated Press:

MADISON — Prosecutors announced Thursday they won’t file charges against loggers whose equipment apparently started a massive wildfire in northwestern Wisconsin, concluding there was no criminal intent or negligence.

The fire began Tuesday afternoon in the woods near Simms Lake in Douglas County, about 40 miles southeast of Duluth, Minn. It consumed 8,131 acres, destroyed 17 homes and forced dozens of people to evacuate before firefighters contained it late Wednesday evening. No injuries have been reported.

The state Department of Natural Resources released a statement Thursday saying logging equipment started the fire.

A logger was operating a large machine similar to an end loader with a circular saw that cuts groups of trees, DNR Fire Law Enforcement Specialist Gary Bibow said. The operator noticed smoke coming from under the cutting head, jumped out of the cab and saw the grass under the machine was burning.

The operator nearly had extinguished the fire when it leaped 40 yards into the trees and raced out of control, Bibow said.

“He thought he had it out, and it took off,” Bibow said. “It climbed into the top of the trees.”

Another member of the logger’s crew immediately called 911, according to the DNR’s statement.

It’s still unclear whether the machine caught fire or created sparks as it was cutting, DNR spokeswoman Catherine Koele said. Neither she nor Bibow knew the name of the loggers’ company.

The DNR said in its statement that Douglas County prosecutors had decided there was no criminal intent or negligence and they had declined to issue any charges.

Douglas County Assistant District Attorney Ruth Kressel said in an email to The Associated Press nothing suggests the fire was started intentionally.

“We realize how tragic this fire has been and the devastation to homes, buildings and to our north woods, but … the origin and cause of the fire lack the requisite intent for criminal charges,” she said.

The fire was one of the worst to strike northern Wisconsin in three decades.

Western Caucus Field Hearing May 2

I have a set of notes, which I have been unable to locate, however here is some information about the hearing I attended last week. In general, the dialogue among Coloradans was more focused on specific practices than the generalized partisan nature of some D.C. hearings. The point of the hearing, after all, was to find out what Coloradans are thinking and doing. But I will give my impressions after I find my notes.

The first panel was Gale Norton and Mike King..Mike is the Director of Natural Resources for the State of Colorado, in the Hickenlooper Administration (D). He started off by saying that that forest health and wildfire issues are beyond partisanship (or similar words).

Here’s a link to his testimony as well as others. Below is an excerpt from Mike’s testimony here.

Recovery From 2012 Wildfires

As the Committee is likely aware, Colorado had an intense fire season in 2012. It started uncharacteristically early and led to a great deal of damage. The Lower North Fork, the High Park, and the Waldo Canyon fires all occurred along the highly populated metropolitan corridor from north of Fort Collins down south to Colorado Springs. Collectively, those fires resulted in six fatalities, scorched 110,368 acres, and destroyed 744 structures.

Recovery efforts began before the fire season was over last summer, and has continued. Federal support in the form of increased funding for the Emergency Watershed Projection program was recently included in the Continuing Resolution for the FY13 federal budget, and will be instrumental in helping our local governments. Nearly $20 million is expected to come to the state as a result of this measure, and treatments will include mulching, seeding, channel stabilization, and contour tree felling. However, with so many resource values in need of attention – water quality, erosion, road corridors, revegetation – even this robust federal support is insufficient to meet the need completely.

Local governments began meeting a few months ago to coordinate their fire recovery efforts, share information about funding, and learn from each other’s experiences. As a part of those conversations, entities that have been engaged in the range of recovery activities have tracked those expenditures. To date, state and local public funds spent on recovery from the Waldo Canyon fire in Colorado Springs has totaled $10.5 million; recovery from the High Park fire in Fort Collins has totaled $9 million. Those funds don’t include the millions that were lost in private property and insurance claims. It is with

this damage in mind that Colorado has worked to elevate forest health and wildfire risk reduction to the highest policy levels.

Federal Role

Authorities

Governor Hickenlooper, in sync with other Western Governors, has identified two federal authorities that have played a key role in Colorado as we work to find a private market for forest products, enhance the health of our forests, and reduce the risk from wildfire. Those provisions are Stewardship Contracting and Good Neighbor Authority.Stewardship Contracting allows the USFS to focus on goods (trees and other woody biomass) for services (removal of this material), and helps the agency make forest treatment projects more economical. Individuals who seek to build a business that requires a reliable supply of timber have consistently reported that long term Stewardship Contracts provide them with the security they need to secure investments. We support permanent authorization for stewardship contracting.

Good Neighbor Authority allows states, including our own Colorado State Forest Service, to perform forest treatments on national forest land when they are treating neighboring non-federal land. This landscape-scale approach is essential for achieving landscape-scale forest health. Fires don’t respect ownership boundaries. We support permanent authorization for Good Neighbor Authority.

Fire Suppression

Early response to wildfires is essential to ensure public safety, reduce costs, and minimize damage to natural resources. Western Governors have repeatedly noted their concern with the ongoing pattern whereby land management agencies exhaust the funds available for firefighting and are forced to redirect monies from other programs, including, ironically, fire mitigation work. Raiding the budgets for recreation in order to pay for fire suppression presents a significant problem in Colorado, where our outdoor recreation opportunities on public land are unparalleled. We support minimizing fire transfer within the federal land management agencies, and more fully funding existing suppression accounts.

As far as I can tell, there were no professional journalists at the hearing.If you see news stories that were generated from a journalist attending, please let me know.

Hooray for Transparency!

Here is Region Five’s “Ecological Restoration Implementation Plan”. It is definitely worth a browse, especially if you are a local within or near any of these National Forests. Each Forest spells out what it is doing and what it is planning.

http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5411383.pdf

(The picture is an old one, from fall of 2000. I had been here, salvaging bug-killed trees, in 1991. There was obviously additional mortality after that.)

From the Eldorado NF entry:

Goals include:

Maintain healthy and well-distributed populations of native species through sustaining habitats associated with those species

Use ecological strategies for post-fire restoration

Apply best science to make restoration decisions

Involve the public through collaborative partnerships that build trust among diverse interest groups

Create additional funding sources through partnerships

Incorporate the “Triple Bottom Line” into our restoration strategy: emphasizing social, economic and ecological objectives

Implement an “All lands approach” for restoring landscapes

Establish a sustainable level of recreational activities and restore landscapes affected by unmanaged recreation

Implement an effective conservation education and interpretation program that promotes understanding the value of healthy watersheds and ecosystem services they deliver and support for restoration actions.

Improve the function of streams and meadows

Restore resilience of the Forests to wildfire, insects and disease

Integrate program funding and priorities to create effective and efficient implementation of restoration activities

Reduce the spread of non-native invasive species

New Study: Wildfires can burn hot without ruining soil

Here’s a link to a short article (and video) about the new study, “Hot fire, cool soil,” with a brief excerpt below. The American Geophysical Union demanded that we remove a copy of the actual study, which they provided me earlier in the day, from our website….so I’ve done that. Sorry folks.

When scientists torched an entire 22-acre watershed in Portugal in a recent experiment, their research yielded a counterintuitive result: Large, hot fires do not necessarily beget hot, scorched soil.

It’s well known that wildfires can leave surface soil burned and barren, which increases the risk of erosion and hinders a landscape’s ability to recover. But the scientists’ fiery test found that the hotter the fire—and the denser the vegetation feeding the flames—the less the underlying soil heated up, an inverse effect which runs contrary to previous studies and conventional wisdom.

Rather, the soil temperature was most affected by the fire’s speed, the direction of heat travel and the landscape’s initial moisture content.

And here’s the abstract:

Abstract

Wildfires greatly increase a landscape’s vulnerability to flooding and erosion events by removing vegetation and changing soils. Fire damage to soil increases with increasing soil temperature and, for fires where smoldering combustion is absent, the current understanding is that soil temperatures increase as fuel load and fire intensity increase. Here, however, we show that this understanding that is based on experiments under homogeneous conditions does not necessarily apply at the more relevant larger scale where soils, vegetation and fire characteristics are heterogeneous. In a catchment-scale fire experiment, soils were surprisingly cool where fuel load was high and fire was hot and, conversely, soils were hot where expected to be cooler. This indicates that the greatest fire damage to soil can occur where fuel load and fire intensity are low rather than high, and has important implications for management of fire-prone areas prior to, during and after fire events.

Forest Service Cutting Suppression by 37% in 2014? And Responding to Climate Change?

I picked this up from a Colorado Springs news clip..

Here is the link to the story, below is an excerpt.

Colorado Sen. Mark Udall, chair of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, questioned U.S. Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell Tuesday about how the agency plans to grapple with budget cuts that could impact its ability to fight fire this season.

The forest service expects to add next generation, or modernized air tankers, to its fleet this month, but will still have to deal with cuts to its fire suppression programs. In short, although it has yet to get seriously underway, wildfire season 2013 could be an expensive endeavor for the agency.

As of last week, the 2014 budget was a done deal–and the forest service announced that it will be cutting funds to its fire suppression program by 37 percent. For the committee of senators from Oregon, Alaska, Wyoming, Colorado and Minnesota, that will come as big blow, particularly as the country gears up for another potentially record-breaking wildfire season.

Both fire suppression and preparedness funds were cut, Tidwell told the committee. There are about 87 million acres of forest lands that need fuel treatment–the cutting down of trees, and thinning of forests to make them less of a breeding ground for megafires–but the forest service’s hazardous fuel reduction budget will be focused entirely on red zones, where people live.

That doesn’t mean that other forest lands won’t get the treatment they need, Tidwell said; instead, those projects will be funded by other projects besides hazardous fuels reduction.

The sequester will also impact the agencies wildfire fighting resources–it has cut 500 firefighters and between 50 and 70 engines from its pool, Tidwell said.

“We’ll start off the season with less resources,” Tidwell told the committee. “Because of the sequester it will probably just cost us more money when it comes to fire.”

Watch the two-hour committee hearing and read Tidwell’s witness statement by clicking here.

My other question would be that if the President said that climate change is a priority as in story here, and fires are worse, in some part, due to climate change, then wouldn’t it be logical to increase what you spend on fire?

But as Bob Berwyn points out here. at the same time, the Park Service is getting an increase in the 2014 budget. According to Bob, these increases include:

Key increases include $5.2 million to control exotic and invasive species such as quagga and zebra mussels, $2.0 million to enhance sustainable and accessible infrastructure across the national park system, and $1.0 million to foster the engagement of youth in the great outdoors. These increases are partially offset by programmatic decreases to park operations and related programs totaling $20.6 million.

If we are working on climate change, and the budget is the “policy made real” then WTH??? Is climate change only about helping energy industries go low carbon, or is it also about mitigating impacts? We could easily spend more bucks studying potential future impacts than dealing with today’s impacts. Seems to me you gotta pick a lane.. either fires are worse due (partially) to CC or they are not. If they are, they should be part of the Climate Change budget and actions.

The Fire Policy in Plain English- High Country News

Another nice job by Marshall Swearingen..of the High Country News.. again, it sounds pretty commonsensical (to me), so I continue to wonder what all the brouhaha (discussed in previous posts as a “Wildfire in a Chiminea”) about fire policy was really about? I hope if a fire is close to me, people are managing it on some practical principles and not the conceptual “buddy system”. Just sayin’..

Thanks to Marshall, for taking the time to ask someone who knows and explaining it in ways that people can understand.

Here’s the link, and below is an excerpt. Any potential clarifications by people on the blog would be appreciated.

1) Was the fire human-caused?

If so, the Forest Service will work to immediately put it out. The agency doesn’t want to encourage folks to light fires willy-nilly, thinking they’re helping the forest. And there are legal liabilities associated with letting a human-caused fire burn. This includes any prescribed burns that jump their lines. Interestingly, the Park Service may allow human-ignited fires to burn because in some of the smaller park units, according to Sexton, “they feel that they have a deficit of fire on the landscape, and they want to take advantage of any start.”

2) Where is the fire?

Certain areas in forests, primarily in wilderness areas, are identified as places where natural fire can safely play a beneficial role in maintaining healthy ecosystems. Fire helps check the spread of insects and disease, and some ecosystems, like ponderosa forest, are adapted to periodic low-intensity burns that clean out the understory. Each individual National Forest decides where fire could serve a restoration purpose, and those areas are identified in that forest’s management plan.

3) When is the fire?

Even if a fire is ignited by lighting in wilderness, it may be a candidate for suppression if it would burn habitat, such as a nesting area, that’s critical during a certain time of the year. Timing during the fire season also factors into other criteria, like risk: a fire started early in the fire season has a greater chance of speading and becoming a danger.

4) What do the locals think?

In 2012, the Forest Service changed its fire policies to emphasize pre-season planning with other agencies, local firefighters and landowners. The agency may have identified an area as being suitable for restoration fire, but if the owner of a private inholding is opposed, for example, that’s a significant factor in the agency’s decision.

5) What are the risks?

This includes danger to public safety and private property, plus risks to fire fighters. Challenging terrain, like steep, rocky slopes and dense forests, could make the fire difficult to manage if it grows.

6) What’s the long-term benefit?

This is basically a cumulative weighing of restoration benefits versus potential risks. If it looks like the fire could be allowed to run a natural course for the remainder of the fire season without getting out of hand, it’s a candidate for “let burn.” But if it looks like it could blow up and get expensive to fight, or move into areas that endanger safety or property, it may be put out.

7) What’s the plan?

Prior to 2009, the Forest Service would decide shortly after a fire started whether to suppress it or manage it for restoration, and the agency was expected to stick to its plan. Changes to federal fire policy in 2009 allow the agency more discretion throughout the whole process, meaning fire-line officials can change their minds as fire conditions change.

Even when the Forest Service is “letting it burn,” the term is a little misleading. “None of these fires are just ‘let burn,'” says Sexton. “Any time we make a decision to allow a wildfire help us achieve a restoration objective, that fire is carefully managed from ignition until it’s out.”