This week, the Ravalli Republic had yet another glowing article about a “thinning” project around the very popular Lake Como Recreation Area of the Bitterroot National Forest. The paper billed the project as “an effort to protect the forest from a mountain pine beetle invasion.” Here’s a snip:

Bob Walker and his small crew have been working to thin out the forest around the Lake Como Recreation Area since last year….“We need to be doing more work to get ahead of the pine beetle. It’s sad to see our forests dying right before our very eyes.” The project his crew is working on now has that focus in mind. Over the past year, Walker’s loggers have removed about 60 percent of the trees from most of the recreational sites in the Lake Como area in order to give the remaining trees a fighting chance when the mountain pine beetle arrives en masse.

And now, for the rest of the story, which the Ravalli Republic reporter has been provided a number of times over the years as the Lake Como “forest health” project does its best Energizer Bunny impersonation and “just keeps going…. and going…and going.”

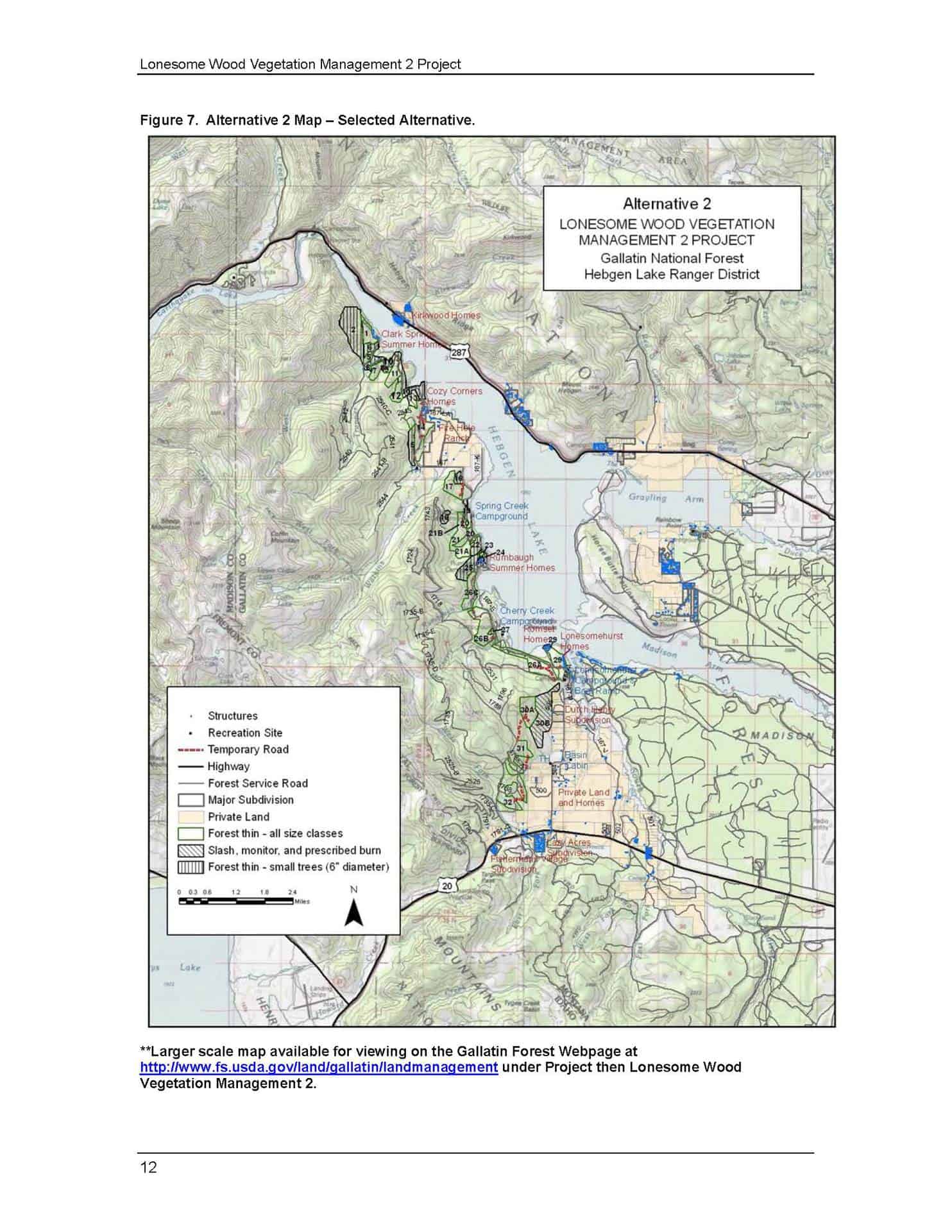

But first, here’s a link to the official 2011 Decision Memo for the “Lake Como Recreation Area Hazard Tree Removal Project.” Yes, this time I was able to rather quickly and easily find a recent decision memo on a Forest Service website. So perhaps this one-time success will develop into a trend of good luck with Forest Service websites. Of course, in order to get to the “Projects” portion of the website I first had to click on the “Land and Resource Management” link, which includes a somewhat idyllic and pastoral picture of horse logging on the Bitterroot National Forest….which must have taken place at least one time in the past, although I must admit I haven’t heard of any horse logging on the Bitterroot National Forest for quite some time. But, hey, why not give the public the impression that horse logging is common-place on the forest, right?

OK, on with the rest of the story, courtesy of the local group Friends of the Bitterroot (which, I should point out, counts former loggers, retired Forest Service district rangers, biologists and even the son of the Bitterroot National Forest Supervisor from 1935 to 1955 in its leadership).

Probably the most popular and well used trail on the Bitterroot National Forest snakes through an old growth stand of big ponderosa pines on the north side of Lake Como. The first half mile of the trail is paved to make it handicap accessible. Benches and interpretive signs have been placed as amenities along the way.

Darby District Ranger Chuck Oliver decided to improve the experience of what was a beautiful old growth pine forest by slashing and burning undergrowth. In April 2004 the area was torched on a hot dry day. The fire erupted out of control and burned many of the prime old growth pines.

Then the Forest Service salvage logged the area and burned the logging slash.

Subsequently pine beetles invaded many of the fire stressed trees and a bunch more big old growth pines died.

This offered the Forest Service another opportunity to salvage log big trees in 2006.

Then the logging slash from that logging was burned.

The end result of the Como fiasco is a handicap accessible paved trail through a thrice burned, twice logged remnant of old growth pine studded with many big stumps.

The new interpretive signs do not tell the reader that the fire was set by the Forest Service and do not point out that the beetle infestation area matches the burned area. The public is given the impression that the events were all natural rather than the results of Forest Service [mis]management activities.

Keep in mind that here we are in 2013 and the Forest Service is still logging trees in the Lake Como Recreation Area, including what appear to be (see photo above) some rather nice looking, green, large-ish ponderosa pines trees. This would all be funny, if it wasn’t so sad and frustrating. And, isn’t it absolutely amazing how none of the timeline or facts above about the Lake Como Fiasco make it into this reporter’s “feel good” story? Equally so, how come none of this history made it into the “background” portion of the Bitterroot National Forest’s 2011 Decision Memo?

But wait…there’s more! The Forest Service now is analyzing yet another project for the area called the “Como Forest Health Project.” Yep, this is truly a logging project that keeps on giving.

Update: The Alliance for Wild Rockies has provided a copy of AWR’s scoping comments on the proposed “Como Forest Health Project.”