Photo of a scoured stream channel in a roadless area that resulted from a flash flood in a burn area in 2009 in South Fork Salmon River drainage, west central Idaho.

A guest post by Michael Dixon.

I believe the line between science and advocacy is often blurred in natural resource management. I am convinced that often the people doing the science and the advocacy do not know the difference. The public and special interest groups often cite their favorite “science” that supports their point of view, and down play the other views, or worse yet, actively discredit other points of view. To me this is advocacy and politics, using selected science to support your position. This is common and obviously your or my science is better than the opposing positions.

This has been taken a step further by advocacy groups who fund their own science, I’m starting to see more of this or maybe I’m just more aware of it.

Locally where I live the Wilderness Society has their own report on how to deal with fire dependent Ponderosa Pine Ecosystems. They presented this to the FS as science a nice little booklet with glossy photos and citations. I think The Wilderness Society believed that this was state of the art science, and the FS should adopt their recommendations. I skimmed through it and got the impression that the “science” was pretty much what the FS had known for years concerning Ponderosa Pine ecosystems, with the WS’s recommendations on how to manage it was what you would expect from them with the slight admission that thinning stands by logging might be acceptable in some limited cases. I am sure there are cases where the Forest Products Commission does something similar but recommends much more logging as the proper course of management. To me this is just political advocacy with a sprinkling of selected science that the advocates tout as science.

What is more disturbing to me is when researchers and scientists do not appear to know the difference between science and advocacy. An example that I know is as follows: The local Forest Fisheries biologist hired a college professor with a doctorate in fisheries to monitor macro invertebrates in recently burned and unburned drainages to see what effects fire had. Sounds reasonable, he found that the macro invertebrates in the wilderness streams he sampled were more numerous in the burnt drainages. More sunlight and nutrients in the water in the burned drainages, makes sense. Then he sampled some steep gradient streams outside the wilderness. This was the year after the 1997 flood and many of these drainages experienced channel scouring debris torrents. He sampled two of the channel scoured drainages; one had a road in it and was salvaged logged by helicopter after the 1994 fires. The other was in a roadless area. He found only two species of macro invertebrates instead of the five or six species he had found in the other streams. His conclusion was the stream in the roadless area was an anomaly, where as the lack of species in the other stream was due to salvage logging. A better conclusion might have been channel scouring debris torrents remove macro invertebrates. This particular scientist was one of the authors of a widely circulated science paper that sharply criticized salvage logging after fires.

Fisheries biologists, as do many biologists, tend to favor natural conditions as that’s where the species evolved. Roadless and wilderness areas tend to be favored for their pristine/natural conditions. The science report for the ICBEMP (Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Plan?) did a study comparing fish habitat to road density, and they found a correlation between road density and fish habitat, generally the higher the road density the poorer the fish habitat. I can believe this is generally true, the higher road densities probably also correspond to higher levels of development. I believe there were a few drainage basins in the ICBEMP study area with higher road densities and good fish habitat. The fish biologist for the science report was concerned that the high road density/good fish habitat areas are threatened by the road density. A better response may have been to ask why they are different from the other areas. Is there something to be learned in areas where good fish habitat exists in areas with a high road density? I think this would be important to ask when the big emphasis is restoration.

The study has been taken forward into Forest Planning as a watershed condition indicator. This is considered by some as a direct cause and effect. I would tend to favor more stream based indicators such as; stream temperatures, pool riffle ratios, man made fish barriers, bank stability, riparian conditions and large woody debris. The Boise, Payette, and Sawtooth Forests in Idaho adopted road density as one of the watershed condition indicators, however the ESA consultation process with Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries went a step further and added the following descriptions to road densities: less than 0.7 miles per section is functioning properly, 0.7 to 1.7 miles per section as functioning at risk and anything over 1.7 miles per section as functioning at an unacceptable risk. This categorization basically calls all areas that have been developed for timber management in the past an unacceptable risk to listed fish species due to road density.

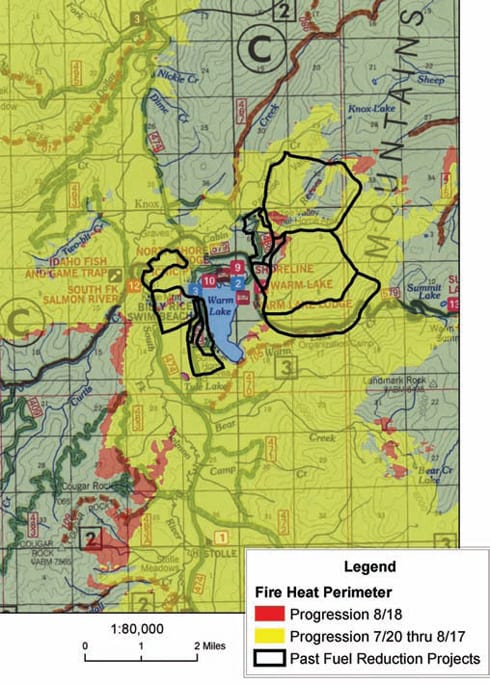

This all seems rather ironic in west central Idaho where wildfire, especially in 2007, primarily in roadless and wilderness areas have had a considerable impact, on both old forest structure and stream channel condition. Hundreds of stream channels have been scoured by flash floods and debris torrents in the burn areas, leaving raw and unstable banks. Hundreds of thousands of acres of old forest have been lost to wildfire. Is ecologic integrity assured in roadless and wilderness areas? Not from what I have seen.

About the Author

Michael Dixon has over 30 years of Forest Service employment, including over 25 years as a member of project level NEPA teams. He has worked on two Forest Plans as well as post plan project level implementation and monitoring. He has been a member on Burn Area Emergency Recovery (BAER) teams on 6 major wildfires.