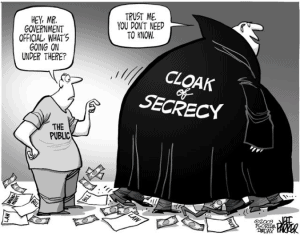

In my experience, there have been lots of controversies where the issue is about what scientific information was considered by an agency but was suppressed or ignored by an administrator, often for allegedly political reasons. It’s not unusual for the results of litigation to turn on documents that show an agency decision being arbitrary and capricious (violating the Administrative Procedure Act) because it is not supported by the record. But do those kinds of documents have to be available to the public, and what if they weren’t? The Supreme Court will be addressing such questions in U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service v. Sierra Club. The case involves the Freedom of Information Act, and its requirement to make government records available subject to exceptions that may cause harm, in particular protection of an agency’s “deliberative process.” (This exception generally lines up with requirements for what must be in an agency’s administrative record for a decision.)

The dispute stems from the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2011 proposal to change how it regulates power plants’ cooling water intake structures, which can crush or boil fish and other aquatic creatures.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service advised the agency on how the plan would affect threatened and endangered species. The services crafted draft opinions that said the EPA’s proposal was likely to harm protected species, but they later changed their conclusion and issued a “no jeopardy” finding.

When the Sierra Club used FOIA to get records related to the consultation process, the agencies withheld the draft opinions. After years of litigation, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 2018 ordered the government to turn over the records.

The Trump administration in October asked the Supreme Court to step in, arguing that the circuit court ignored FOIA Exemption 5, which protects records from an agency’s “deliberative process.” The Sierra Club countered that the documents were labeled drafts but functioned as final opinions.

While this article doesn’t talk about it, the major federal environmental statutes have requirements to use the “best science,” including the Endangered Species Act involved in this case, but also NEPA and the Forest Service Planning Regulations. Agencies must prove they have done this by “showing their work.” This includes disclosing contrary science, and providing the rationale for not relying on it. It seems to me that any changes in the use of science or how it is viewed would be relevant to this requirement and must be explained to the public. This is probably why there are comments like these on this case:

Margaret Townsend, a Center for Biological Diversity attorney who focuses on government transparency, said her group will be watching the case closely, as the Supreme Court “has a crucial opportunity to tell agencies they can’t hide science at the expense of our endangered animals and plants.”

Brett Hartl, government affairs director for the center, noted that expanded use of FOIA’s “deliberative process” exemption could allow the EPA and others to block disclosure of critical documents that explain agency decisions.

Lewis and Clark Law School professor Daniel Rohlf said a win for the government at the Supreme Court could help agency leaders overrule their own scientists and other experts.

Here’s what the government would like us to believe (according to the apparently pro-government-secrecy advocates the Pacific Legal Foundation):

“And here the agencies decided that the draft should not be finalized because further consultation was necessary, and then actually engaged in more consultation before issuing a final opinion.”

Consultation with whom, I wonder. Since the Supreme Court agreed to review the case, the assumption is they would like to reverse in favor of the government. The Sierra Club may decide to fold, also because FOIA has been amended since this case was filed to restrict the use of this FOIA exemption and promote greater disclosure.

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com