A few weeks ago, I posted this on the West Bend Vegetation Project, and asked the question “why was this successful?”

Matthew asked the question “could it be because the Deschutes was willing to negotiate with the objectors during the objection process?”

He compared it to the Colt Summit collaborative project, that we’ve discussed many times on this blog. Here’s exactly what he said:

This compares to some other high-profile CFLRP projects, such as the Colt Summit Timber Sale on the Lolo National Forest, in which the Forest Service was completely unwilling to make any modifications or remain flexible even going so far as the Lolo Supervisor telling conservation groups during the appeal resolution meeting “We’re fully funded for this project and we’re not making any changes.” The result was the first timber sale lawsuit on the Lolo National Forest in over 5 years.

So I went back to the record and asked the question.. had the Colt Summit folks changed the proposal based on public feedback?

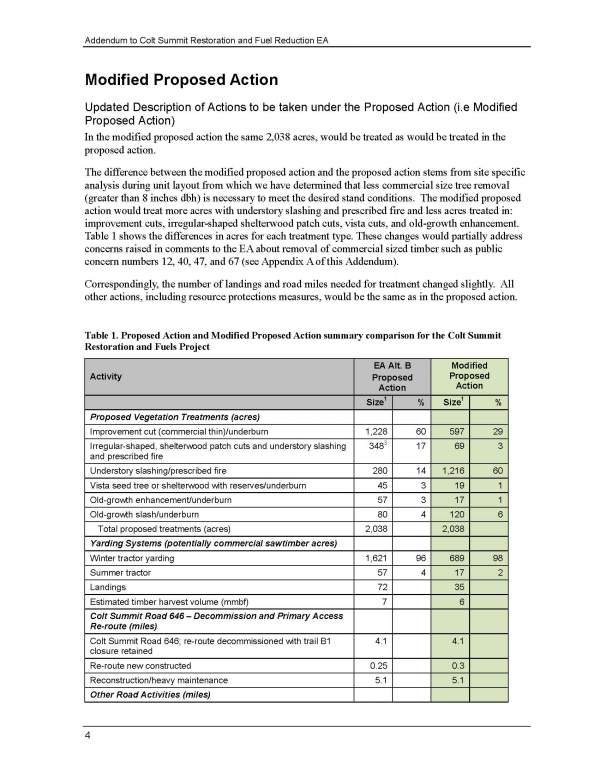

I had a vague memory of a table that showed changes.. and sure enough, in this link there it was!

But it looks like it was based on public input and not on the result of an appeal resolution meeting. So here’s what appears to have happened (FS people invited to chime in):

The Forest Service initially proposed 1228 acres of commercial thinning when they first presented the project to the public. The Proposed Action was first presented to the public on February 6, 2010 in an official scoping notice (legal advertisement published in the Missoulian newspaper of record). Later, in response to public comment and field findings, the Forest Service developed the modified proposed action, which reduced the commercially thinned acres down to 597 acres.

So it sounds as if, based on what Matthew said, the appellants on Colt Summit might have been satisfied and not litigated if the acres had been reduced still further. I like this because it is honest.. it’s not really about the FS breaking the law, it’s about having power over the outcome.

But the public can’t know for sure, since Mr. Garrity pointedly refused to say what outcomes he wanted, when I asked in this email exchange.

Here’s what Mr. Garrity said:

We do think is is odd that the Forest Service was non-responsive to our comments and appeal and yet we are supposed to believe that if we debate this on a blog site it will bring changes to the project.

So it didn’t seem important to him to inform the public (whose land it is) about his concerns. The FS worked with the public, though, as required by law and regulation.

Here’s the process for Colt Summit was as follows (steps of official public input in bold):

1. Proposed Action Developed by Forest Service considering collaborative input from previous projects

2. Scoping – Proposed Action provided to public for review and comment

3. Public concerns and issues identified and alternatives developed to respond to public’s scoping comments

4. EA Prepared to analyze effects of the proposed action and the alternatives and to display this analysis for public consideration

5. Public Notice – Legal Notice published on December 10, 2010 to inform public that EA and Draft Finding of No Significance (FONSI) is available for public comment.

6. Comment Period – public provided comments on EA during 30 day comment period

7. Modified proposed action prepared and analyzed to respond to public comment. Acreage of commercial thinning reduced from 1228 to 597 acres.

8. Decision Notice and FONSI signed on March 25, 2011 selected the Modified Proposed action

9. Appeal Period – 45 day appeal period begins day of decision

With Colt Summit, there were three additional comment periods with reaffirmation of the original March 25, 2011 decision. None of these decisions were subject to appeal because the Forest Service did not change the original decision.

So Mr. Garrity’s (secret) opinions should count more than the other members of the public because…if the FS doesn’t do the (secret) thing that his group wants, then the project will be delayed in years of litigation. Kind of quasi-extortional. Just some kind of formal mediation process, prior to litigation, would help this kind of thing, in my view, or at least should be tried. Congress.. this would be a simple pilot to try out and not invoke “rolling back environmental laws.”