Here’s a link and below is an excerpt.

On Monday, the court agreed to referee the dispute pitting environmentalists with the Portland, Ore.-based Pacific Rivers Council against the U.S. Forest Service over decision-making that dates back to the second Bush administration. While the specific case involves 11 Sierra Nevada forests, the eventual outcome could shape everything from who gets to file lawsuits to the scope of future environmental studies.

“Definitely, throughout the West, this could have huge impacts on the moving of projects forward,” Dustin Van Liew, executive director of the conservative Public Lands Council in Washington, D.C., said in an interview Monday.

One key question confronting the court will be whether environmentalists have the “standing” to sue against a general forest plan, as opposed to a specific project proposal, by virtue of their making recreational use of the national forests. To gain standing in federal court, individuals must show they’ve been injured or face imminent injury.

A second major question is how extensively detailed the Forest Service must be when preparing overarching management plans, such as the one governing the 11 Sierra Nevada forests.

“The only role for a court is to insure that the agency has taken a ‘hard look’ at the environmental consequences of its proposed action,” Pacific Rivers Council’s attorneys said in a legal brief, adding that “agencies cannot take a ‘hard look’ unless they have reasonably identified the consequences of their actions.”

Underscoring the case’s potential significance, the Public Lands Council and the affiliated National Cattlemen’s Beef Association secured Supreme Court permission Monday to file a brief opposing the environmental group. Many more briefs, from both sides, are sure to come.

The court’s decision to hear the Sierra Nevada case, sometime during the 2013 term that starts in October, means that at least four of the court’s nine justices agreed to reconsider a 9th Circuit Court of Appeals decision from last year in which environmentalists prevailed.

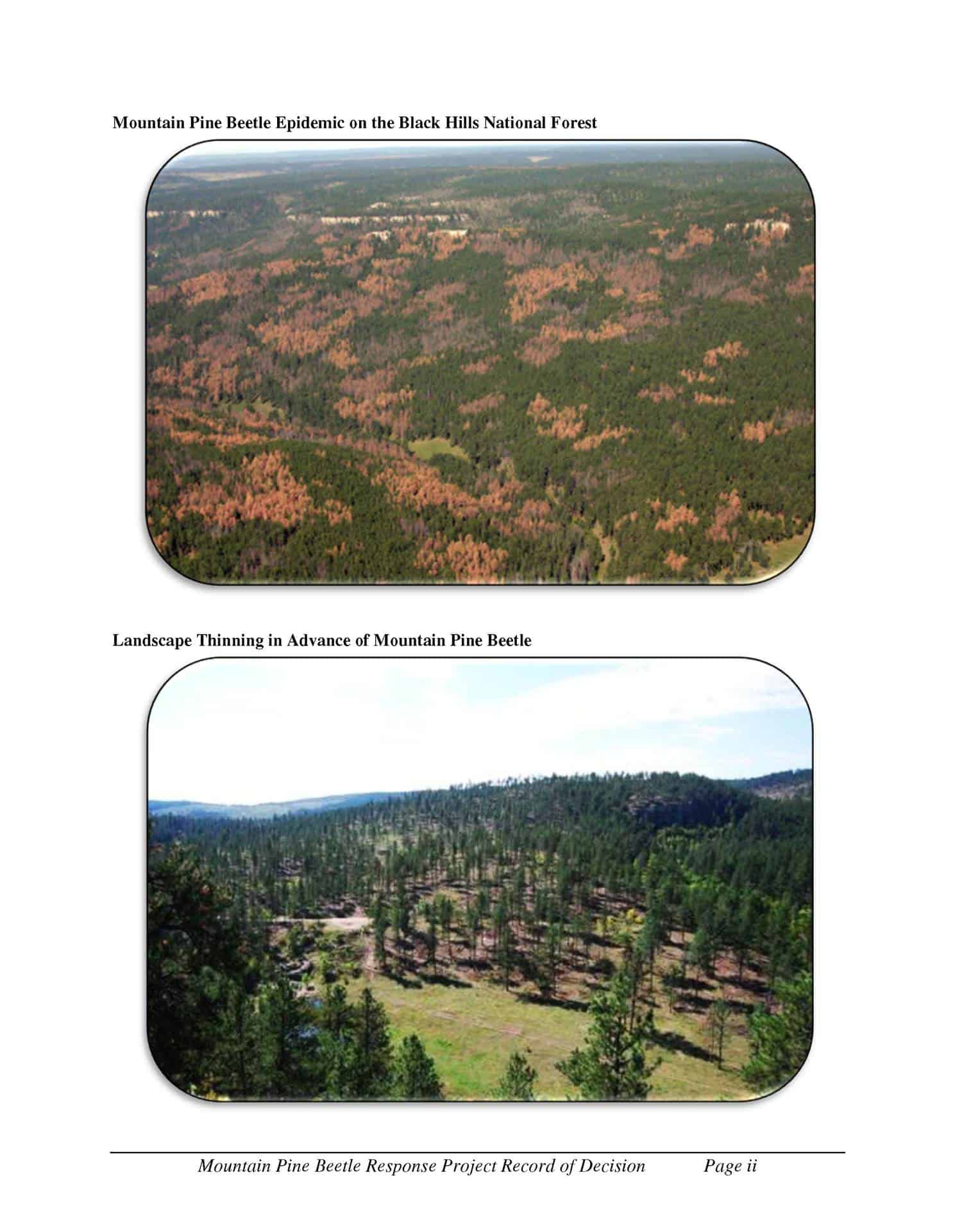

In that 2-1 appellate court decision, the 9th Circuit panel concluded the Forest Service in 2004 failed to adequately study the effect of dramatically revised forest plans on Sierra Nevada fish populations.

“The Forest Service provided no analysis despite the fact that the 2004 (plan) allows much more logging, burning, road construction and grazing,” Judge William A. Fletcher wrote for the appellate panel.

Has anyone actually looked at what they did write about fish? Seems like if they wrote “enough” about everything else in the document they would have also written about fish “enough”.

Funny that Judge Fletcher says that the 2004 plan “allows” more burning, as if that was a bad thing.. prescribed as opposed to wildfires?

Of course, I am not a believer in hypothesized future effects of unknown projects in unknown numbers, of unknown kinds with unknown mitigation requirements in unknown locations…

“My first Sierra Nevada backpacking trip was to the Mineral King area in 2000, during which time I also fished,” Pacific Rivers Council Chairman Bob Anderson, a South Lake Tahoe resident, said in a court declaration used to establish injury and standing. “I plan to continue these activities as long as the management of Sierra Nevada national forests does not prevent me from doing so.”

Of course, forest plans require actual projects to be “management” that could have environmental impacts of the kind Mr. Anderson is concerned about.

This follows a bit of the ocean liner vs. flotillas of dinghies discussions about NEPA documents. As NEPA documents grow in size and area covered, they are increasingly functions of assumptions made about what might happen, and move further from physical reality (“might-could” NEPA). That makes them both easier, and more important, targets for litigation. The idea of humungo-NEPA makes the ultimate disposition dependent on the vagaries of random sets of judges determining what is “enough,” and or small sets of people at DOJ and for groups working to settle. The nexus of decision making moves further from the area impacted, and from those familiar with the actual land and people most impacted by the decisions. I don’t think that that’s a good thing.