I looked this Act up on Wikipedia and it turns out that the same (?) bill seems to have been introduced in 2011 (and dates back to 1993?) by the same folks with testimony by Carole King starting in 1994. Nevertheless, we are assured the New York Times writers, Mike Garrity of Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Carole King, of singing fame, of this op-ed that it’s particularly important to do it now because:

To be fair, the Obama administration also pursued some of those actions. But the current administration’s zealotry threatens the region’s wild landscape and rich biodiversity…

Of course, when the Times writes about the interior West, we can assume that we are dealing with the imperial gaze. There are a couple of interesting points I’d like to draw out, but would like to hear from people who know more about the bill and about the history (and the other Rocky Mountain Front Wilderness additions and how they fit together), and to link to our recent discussions, what are “Wilderness Recovery Areas?”

Big Gulps Mean Big Targets. There is a reason that the FS and partners aren’t usually thrilled about “big gulp” projects or “landscape scale restoration via large projects”. They mean big total numbers that can be used in media campaigns, and attract big attention from folks who are of a litigious bent.

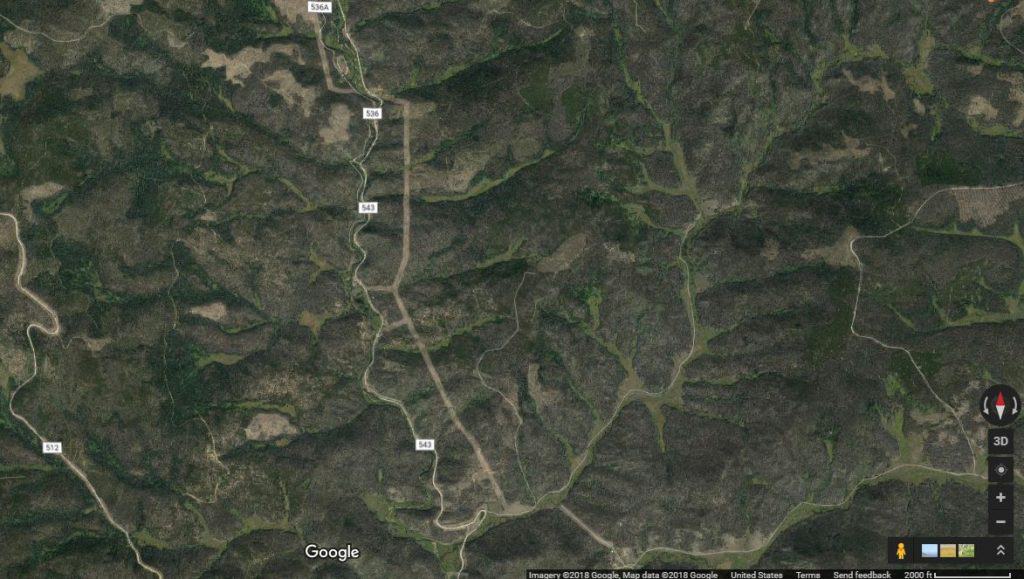

In August, a three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit voted unanimously to halt a planned 125-square-mile logging and burning project in the Payette National Forest in western Idaho. The court concluded that parts of the project ran counter to the forest’s management plan.

Under that project, so many trees would have been cut that the forest would have no longer provided elk or deer with the cover they need. Forest streams would have been filled with sediment from bulldozers building miles of new logging roads — further damaging the native fisheries for which the Northern Rockies are internationally famous.

Without looking at the EIS, I think “the forest no longer providing elk and deer the cover they need” is probably an overstatement.

Forest streams “full of sediment”? Doesn’t the State of Idaho have water quality requirements? Yes, they do, in fact they have audits and a continuous improvement program. I did not get the “full of sediment” feeling from reading the 2016 audit found here.

All Roadless to Wilderness

Under the 2001 Rule, the only things you would be kicking out to change to Wilderness are pre-existing oil and gas leases (before 2001 RR or possibly gap when 2001 RR was enjoined), OHV’s and bikes. But that’s based on reading the Maloney summary linked in the op-ed here and not the whole bill.

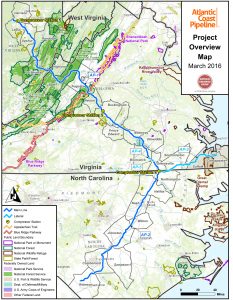

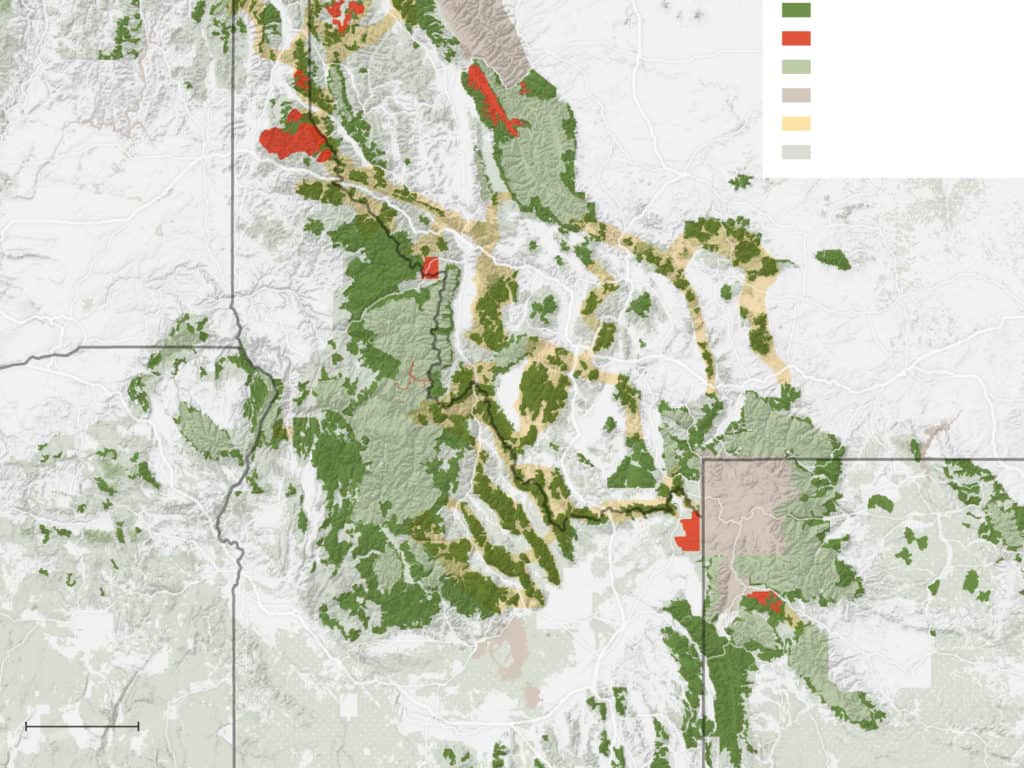

Designate all of the inventoried roadless areas in the Northern Rockies as wilderness, protecting 23 million acres of land that is home to vital ecosystems and watersheds

Establish a system to connect biological corridors, ensuring the continued existence of native plants and animals

Keep water available for ranchers and farmers downstream until later in the season when it is most needed

Allow for historic uses such as hunting, fishing and firewood gathering

Protect forest canopies that absorb greenhouse gases

I don’t know many folks who gather firewood in wilderness, nor in roadless areas… because they gather firewood near roads to get it home.

Et tu Wikipedia?

The entry in Wikipedia says under Opposition to the Legislation here:

Opponents to the NREPA state that there will be a loss of extraction jobs in the northern Rockies; mining, logging, and oil/gas production as a whole account for many of the jobs in the five affected states. [5

But if they’re already Roadless, then how much mining, oil and gas, and logging is going on? This is all very confusing. It would be great if every Wilderness bill or RWA or any special designation, for that matter, would simply have a table of “what’s currently allowed in terms of plans/rules/designations currently” “what will not be allowed under the new designation” “what existing users (actually on site, not potential) will not be allowed to continue their uses” and “what do we know about where those people will go.” IMHO,so much drama and needless carbon -impacting electrons could be saved by a standard Change Of Use Table for every potential change in designations!It also directly would acknowledge that the kicked out folks will go somewhere else and perhaps introduce opportunities and resources for helping them transition as part of the designation process.