They are a little ahead of the Helena-Lewis & Clark discussed on Nov. 29. They are taking comments on their draft plan and EIS. I haven’t read either, but this article provides an overview. Here’s the big picture:

“The purpose and need for revising the forest plan is the changed economic, social, and ecological conditions in the plan area that have occurred since the current forest plan was approved in 1996,” Dallas stated this fall when the draft was released for public review. “These changes include the spruce beetle infestation, closure of mills and timber-related infrastructure in southwest Colorado, changes in communications technology, increased development along the Forest boundary, and the need to shift fire management direction focused on suppression to the use of fire for resource benefit.”

Unlike what we saw on the HLC, this seems to reflect some of the issues that preoccupy this blog (especially the last item recently). Similar to the HLC, there are only two action alternatives, but they are the more traditional left and right of the proposed action (more or less active management).

Alternative B, the draft plan that the Forest is proposing, provides for a balance of multiple uses; Alternative C would increase acreage available for multiple uses and reduce the amount of management areas; and Alternative D would propose less active management of resources and increase semi-primitive, non-motorized opportunities.

I think the planning process can work with a small number of alternatives if they are well-designed to address the relevant issues and impacts and if, as the Rio Grande says here, the parts can be mixed and matched to produce a final preferred alternative that is within the range of what was in the DEIS. Here’s the Forest’s explanation of what their plan does:

Blakeman said the draft plan is broken down into: overarching goals that provide “big picture” guidance such as protecting water resources and terrestrial ecosystems and contributing to economic sustainability; desired conditions representing the vision of what the Forest should look like in the future; concise, measurable objectives, which guide the process and timeline to attain the desired conditions; and standards, guidelines and management approaches that provide constraints and/or site-specific direction. Blakeman said standards and guidelines are harder to change once in place but management approaches can be changed to adapt to changing conditions on the ground.

“Management approaches” are a possible red flag. I’ve seen them used where the standards and guidelines are needed. If the Forest can change or ignore management approaches, this has to be recognized in the effects analysis. And they shouldn’t count towards meeting requirements for plan components (like diversity) because they are not plan components.

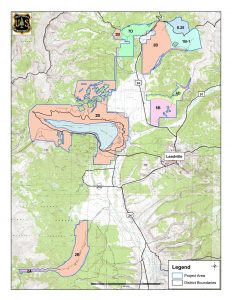

One other pet peeve. Why can’t they use map colors that mean something, like mirroring the active/passive management scheme?