The attached Powerpoint Chojnacky–NWSA Wilderness Presentation 10-25-19 includes complete notes on the slides by the authors. This post is longer than usual, as it involves original material. Many thanks to Cindy and Dave for posting here!

The PowerPoint and notes are a presentation we did October 25 at the National Wilderness Stewardship Association (NWSA) in Bend, OR—an ecletic mix of agency wilderness managers, researchers, volunteer stewards (such as “friends” groups interested in trail maintenance for a particular wilderness) and other non-government entities.

Our presentation was based on observations in hiking 60 wilderness areas (including a few other protected designations) in 11 states over past seven years. We found, oddly, that much wilderness is underutilized and unknown—while a few areas with good trails, good information or well-known features are overused and get the most management attention.

I The Wilderness Act- Ends and Means

Policy analysis focused on “legislative intent”—what did Congress intend? Readers can follow my analysis of the Act’s STATEMENT OF POLICY SECTION 2 in more detail in the PowerPoint notes. In paraphrasing 2 (a)—the Act states an intent to “secure for the American people…the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness,” and to designate wilderness areas which “shall be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people.” Therefore, the purpose for wilderness is people’s use and enjoyment—e.g. wilderness experience.

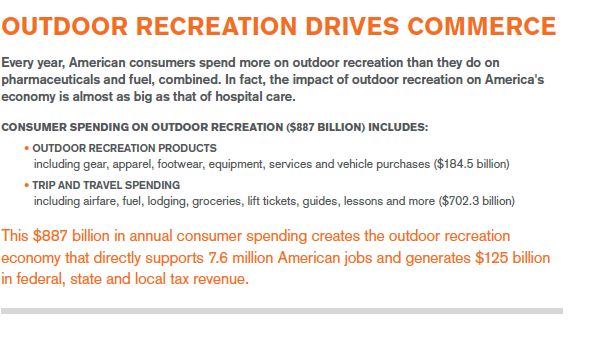

The task of management agencies is also spelled out: “these shall be administered in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness…” Unimpaired could be called wilderness quality. “In such manner” is the job of wilderness administration with wilderness quality the means for achieving the Act’s purpose or end: people’s use and enjoyment of wilderness (experience). Much wilderness research, management and activism have focused on wilderness quality—and particular overused areas have received the most study and management concern. We concluded that focus only on wilderness quality—the means—if ignoring the overall purpose or end—wilderness experience—could treat the wilderness visitor as a threat or nuisance.

The Act’s most repeated word is “use” (32x). SECTION 4 on USE OF WILDERNES AREAS starts with a long paragraph (a) aimed to ensure that wilderness management agencies retain their original mission and authorities along with the new task (b) of “preserving the wilderness character of the area.” This paragraph lists six “public purpose uses”: four we labeled experience (recreational, scenic, educational and historical) and two quality (scientific and conservation).

SECTION 4 (c) lists 10 PROHIBITED USES—probably well known to all—including commercial enterprise, roads, motorized equipment and mechanical transport. An exemption—”except as necessary to meet minimum requirements for the administration of the area for the purpose of this Act”—might be the basis for Forest Service strict “minimum tool” regulations for wilderness management. For example, primitive tools such as cross-cut saws were probably appropriate for trail work in the first decades after the Act was passed because national forest wilderness included a vast legacy trail system that was built for transportation with stock that was still being regularly used for forest management. But today most Forest Service Guard Stations are closed; and long gone most stock and skilled field personnel that regularly cleared trails in course of duty. In addition, 1960-1990 was an era of relatively stable weather, small fires and minimal trail damage. Perhaps we should relook at the Act’s exemption for select use of chainsaws in some areas where 21st century climate-related mega-fires, unprecedented avalanches, and other causes of tree mortality have blocked many trail miles with downfall—if public access is within the Act’s purpose.

Interestingly, the largest “use” word tally (12) is under SPECIAL PROVISIONS (d) is preexisting “prohibited” uses that may be exempted such as grazing, fly-in airstrips, commercial outfitter camps and so forth. The Wilderness Act appears to be a bold experiment in land use management to benefit the public with rather broad exemptions—not a mandate for rarely-visited, off-limits sanctuaries. Perhaps these are needed, but we will need a new law to do this.

II. Wilderness Experience Sample (many great photos of the authors’ experiences are in the Powerpoint)

Finally we attempted to quantify our own wilderness experience in 309 days of hiking about 3,339 miles in 60 wilderness areas in Eastern and Western states—spanning conifer forest, hardwood forest, desert and seashore. We identified six barriers to our experience and then evaluated each wilderness as to which barrier(s) severely impacted our experience—e.g. we would not repeat the trip for “enjoyment.” All but nine areas had at least one show-stopper barrier—most due to trail design or maintenance issues. We closed our presentation with a few ideas on shifting focus to visitor-focused management mainly in brainstorming mode.

III. Studying, Monitoring and Managing Wilderness Experience

Our analysis of words and wilderness experience are somewhat subjective because we began this project with a sense that our wilderness experience had been declining in recent years but were not sure why (furthermore, attempts to fund systematic studies of emerging enviromental issues in wilderness were met with disinterest; so we decided to just “go to the wilderness”). We’d love to see more systematic study of wilderness experience over the entire National Wilderness Preservation System. But, as one speaker pointed out at the NWSA meeting: much funding is spent on getting more wilderness acreage while only “pennies” are spent, relatively, on wilderness stewardship—let alone evaluating the wilderness experience.

Ironically, in the same sentence on wilderness in the 1964 Act SECTION 2. (a) that mandates “the preservation of their wilderness character” is also a mandate for “gathering and dissemination of information regarding their use and enjoyment as wilderness”—a type of report we have never seen. Instead “wilderness character monitoring” seems to be sole emphasis of agencies’ wilderness reporting—even though the Act does not mandate such a report. Nor is the science of wilderness character monitoring developed to the point where consistent indicators (and electronic protocol) would allow scaling up information to evaluate the National Wilderness Preservation System.