According to ClimateWire, Rep. Ryan Zinke, President Trump’s pick to lead the Interior Department, “has told senators he’s interested in transferring the Forest Service from USDA to Interior, where the forest agency’s predecessor resided before 1905.”

Uncategorized

Seasonals Exempt from Federal Hiring Freeze

According to this article, “”Park rangers and firefighters hired each summer to serve the nation’s public lands appear to be exempt from the freeze, according to a memo issued Tuesday evening by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.”

The memo says this applies to, “Appointment of seasonal employees and short-term temporary employees necessary to meet traditionally recurring seasonal workloads, provided that the agency informs its OMB Resource Management Office in writing in advance of its hiring plans.” And others.

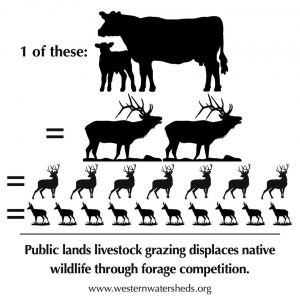

Federal Public Land Grazing Fee Drops 11% , Further Undervaluing Public Lands

According to Western Watersheds Project, yesterday federal public lands management agencies slashed grazing fees by 11% on 220 million acres of America’s public lands – including within some designated Wilderness areas. Below is the WWP press release. – mk

LARAMIE, Wyo. – The public lands management agencies announced the grazing fee for federal allotments today, which the federal government has decreased to a mere $1.87 per cow and her calf (or 5 sheep) per month, known as an Animal Unit Month, or AUM.

“This has got to be the cheapest all-you-can-eat buffet deal in the country,” said Erik Molvar, Executive Director of Western Watersheds Project. “Our public lands are a national treasure that should be protected for future generations with responsible stewardship. It makes no sense to rent them to ranchers for below-market prices to prop up a dying industry that degrades soil productivity, water, wildlife habitat, and the health of the land.”

Two hundred and twenty million acres of public lands in the West are used for private livestock industry profits through the management of approximately 22,000 grazing permits. The low fee leaves the federal program at an overwhelming deficit. This year’s fee is a a decrease of 11 percent from last year’s fee of $2.11 per AUM far less than the average cost for private lands grazing leases. The fee is calculated using a decades-old formula that takes into account the price of fuel and the price of beef, and this year’s fee falls far below the level of $2.31 per AUM that was charged in 1980. Additionally, the fee doesn’t cover the cost to taxpayers of range infrastructure, erosion control, vegetation manipulation, and government predator killing – all indirect subsidies that expand the program’s total deficit.

“The subsidy to public lands livestock grazers just got bigger,” Molvar said. “It’s a totally unjustified handout that persists for purely political reasons, with little or no benefit to Americans.”

###

Transition Shout-out to Career Feds

I’ve worked in DC during a couple of transitions, including the last D to R transition. That one was pre-social media, so scrutinizing every miss-step was more difficult. You had to read the newspapers, and there’s only so much space in newspapers. And there are many, many agencies and departments where things can go wrong.

Anyway, it’s hard to describe what it’s like to have the top people replaced and for them to get hold of the reins. Can you imagine running a company that has thousands of locations and employees and responsibilities, and you and your team have never worked there, nor with each other, before? It’s kind of amazing that transitions work as well as they do. That’s because most career federal employees put aside their own partisan views and follow the Constitution, as in their oath of office. IMHO, they deserve a big shout-out for their work this week and in the coming weeks. It’s invisible, and the glue that helps keep the government running.

Here’s a little flavor of “another day at the office”, transition version..via this Washington Post story.

“The ARS guidance was not issued in coordination with other offices at the USDA, department officials said, and partially contradicted a department-wide memo that went out on the same day. The USDA-wide memo, issued by the department’s acting deputy administrator, Michael Young, was intended to offer guidance on “interim procedures” until a new secretary takes over USDA.

Young stressed during a phone call with reporters Tuesday evening that his guidance does not place a gag order on publication to scientific journals, does not place a blanket freeze on press releases, or prohibit food safety announcements.

“The ARS guidance was not reviewed by me. I would not have put that kind of guidance out. My guidance has to do with policy-related announcement and that sort of thing,” Young said during a phone call with reporters early Tuesday evening. “I had my memo drafted before the ARS memo, I was not a part of it.”

Young’s memo, a copy of which was given to The Washington Post, emphasizes that press releases and policy statements must be routed through the office of the secretary for approval: “In order for the Department to deliver unified, consistent messages, it’s important for the Office of the Secretary to be consulted on media inquiries and proposed response to questions related to legislation, budgets, policy issues, and regulations,” said the memo. “Policy-related statements should not be made to the press without notifying and consulting the Office of the Secretary. That includes press releases and on and off the record conversations.”

Young stressed that he is a “career official,” not a partisan appointee, and said that the memo he issued closely mirrored one sent at the beginning of the Obama administration. He also said he shared the memo with Trump transition official Sam Clovis before issuing it.

“This is really just formalizing again what is fairly standard practice within the department. I just felt like, yeah, I want to be cautious because I don’t want any surprises on my watch. I was trying to avoid any surprises,” he said.”

What is the “best” forest value?

Folks, this is from an op-ed by Andy Geissler, a forester who works for the American Forest Resource Council in Eugene, Oregon. He is writing about a previous op-ed on the recent expansion of a national monument in SW Oregon.

The Jan. 12 guest viewpoint headlined “Expanded monument could benefit economy” offers a strange and disturbing perspective on how economic value is placed on certain commodities, and likewise, how Oregon places value on its economy. The context is the expansion of the Cascade Siskiyou National Monument in Southwest Oregon.

The authors assert that “the economic value of tourism associated with an expanded monument would vastly exceed the value of timber that could be extracted.”

I believe the flaw in this approach is that it assumes that whichever commodity generates the most economic value is inherently the “best” or most useful commodity.

…

I can relate to this, as I live very close to the Mt. Hood National Forest in Oregon, which attracts more than four million visitors annually. Those visitors certainly have an economic impact, but most of the folks in the local communities don’t get much of a benefit in terms of well-paying jobs. We’d be much better off if some of the former jobs in the woods, trucks, and mills were brought back — jobs that pay far more than most the recreation and tourism jobs here. And I think we could have both. For us, a more-diverse local economy would be much better than one so largely tied to tourism.

FWIW, two of the 14 homes along my rural road that sold last year were bought as vacation homes. That makes 5 homes now that sit empty most of the year. It is rare that these new owners spend any money here….

Trump will pick former fertilizer salesman & vet Sonny Perdue to be Sec of Ag (and oversee USFS)

As all of us clearly know, the person who ultimate oversees the U.S. Forest Service is the Secretary of Agriculture. Lots of people seem to assume that the U.S. Forest Service falls under the Secretary of Interior, but nope.

The choice for Sec of Ag is a huge deal if you care about public lands because the U.S. Forest Service manages 193 million acres of federal public lands all across the country (154 national forests and 20 national grasslands). That means that the U.S. Forest Service manages 30% of America’s federal public lands legacy. The USFS also manages 33% of the acreage within America’s 110-million acre National Wilderness Preservation System.

Some background information about Sonny Perdue can be found here.

In 2014, Perdue mocked “the left” and “mainstream media” for its coverage of climate change. Writing in an op-ed published in the National Review, Perdue challenged the connection between climate change and drought, extreme precipitation, and other weather events. He also wrote that climate change has “become a running joke among the public” and “liberals have lost all credibility when it comes to climate science because their arguments have become so ridiculous and so obviously disconnected from reality.”

In 2007, in the midst of an epic drought, Perdue implored residents to pray for rain, holding a prayer vigil outside of the Georgia state Capitol.

His track record on environmental issues is not much better. As governor, he championed the expansion of factory farms, and pushed against gas taxes and EPA efforts to enforce the Clean Air Act.

Perhaps Sonny Perdue will host a prayer vigil or two during wildfire season. Maybe he could also ask the Lord to forgive environmentalists for causing all these wildfires.

No, California’s Forests Aren’t Failing to Regrow After Big Wildfires

The following article, written by George Wuerthner, was originally published at Earth Island Journal. – mk

New study about low conifer regeneration lacks context

By George Wuerthner

Recently researchers at UC Davis and the US Forest Service presented a new scientific study that suggested a dire future for forests in California. The study on conifer establishment after wildfires in California found that 43 percent of their study plots did not have conifer regeneration that met Forest Service Stocking Standards, implying that without additional management we may face a future without forests.

The findings were viewed with alarm by some, with some news reports suggesting that California’s forests were not regenerating after high severity wildfires.

To be fair, the study was not intended to review all the benefits of high-severity blazes, but what it lacked was context. First, even the authors admitted that the paradigm used to determine conifer regeneration is biased towards timber production. Besides, there are many nuances in interpretation that were only mentioned in the body of the study that few bothered to review. As a result, the report has generated undue concern and panic among the public that the state’s forests may be disappearing.

With regards to context, the authors, for one, choose to focus on the increase of wildfires in the past three decades, arguing that blazes during this period were more severe and extensive than wildfires in the past. They attributed this to fire suppression, past logging, and other forest management practices which they alleged have led to this significant increase in large wildfires. While these factors likely contributed to the observed greater tree density and fuel loads in forests to some degree, the report ignores the influence of past, wetter climatic conditions on limiting wildfire, and the ongoing drought that is likely contributing to greater fire occurrence.

Furthermore, the study made statements like “the frequency, size, and severity of wildfires across much of the western United States are increasing” without providing a time factor. Inreasing, compared to what? That’s important because there is ample paleo and even historic evidence of large high-severity blazes that have occurred in the past. For instance, during the Medieval Warm Spell between 800 to 1200 AD there is evidence for extremely large and continuous wildfires across the western US, including in California.

Even more recently there was significant climate variation that influenced wildfire behavior and spread. Between the 1940s and 1980s, for instance, the overall climate around the West was cooler and moister than in the decades past. These moist and cool conditions naturally reduced fire ignitions and fire spread. They also facilitated greater seedling survival and hence led to an increase in tree density.

So was fire suppression as important as commonly assumed or did climatic conditions contribute to the increase in tree densities and a reduction in fires? Likely both are responsible, but almost universally fire suppression is given more credit than is reasonable.

This context is important because most current management, including so-called forest restoration, is justified on the belief that human inference with natural processes has created current forest conditions, and thus requires human intervention, usually in the form of logging.

And while California has experienced some large wildfires with extensive high-severity patches, one shouldn’t ignore the fact that the state has experienced one of the longest and most extreme droughts in the past 1,000 years. Given such historic drought conditions, one would expect there to be significant wildfires.

And when considering the climate change context, it would help to look at wildfires (as well as other natural processes like bark beetles) as helping to thin forests to help them adjust to new climatic parameters. The lack of conifer regeneration may be viewed as a good thing that is balancing the vegetation’s hydrological needs with available soil moisture.

The Forest Service, however, requires a certain amount of conifer regeneration within five years after logging. If there is insufficient natural regeneration, the Forest Service requires timber companies to plant conifers on the site, often creating even-aged, single species plantations that are biological deserts.

But is this silvicultural standard an appropriate way to measure the ecological effects of wildfire? I would argue it is not.

Having ample, rapid, and dense conifer regeneration is only important if your goal is logging for wood products. The focus on conifers skews the report because it gives the impression there was little vegetation on many of the plots. However, on most sites there was vegetation growing including regeneration of many native hardwoods like bigleaf maple, Pacific madrone, and black oak — all of which sprout from root crowns after a fire.

In addition, on many plots, shrubs like those from the ceanothus genus (California lilac, soap bush etc.) colonized burn sites, particularly high severity burn ones. These shrub species control erosion, and are important nitrogen fixers that help restore soil health. Other shrubs common on burn sites, like chokeberry and bitter cherry, are important food sources for wildlife.

In fact, in many instances, it is standard Forest Service practice in the Sierra Nevada and elsewhere to use herbicides on these nitrogen-fixing shrubs to hasten the establishment of conifers, therefore short-circuiting the natural ecological succession, and reducing the replacement of important nutrients in the soils.

In addition to shrubs, the report shows that there was a documented increase in “forbs” or flowering plants. These plants play an important role in forest ecosystems. Oaks, for instance, are an important source of mast (acorns) that many wildlife species from acorn woodpeckers to black bears feast upon. Many bird species utilize the shrub habitat for nesting and feed upon shrub, berries, and fruits. Shrubs are also consumed by deer and other browsing wildlife. And flowers are both consumed by wildlife and provide sources of pollen and honey for insects like bees and wasps.

But none of these ecological values were mentioned in the study.

Using the silvicultural standards for conifer regeneration that requires a certain number of confer seedlings established within five years also ignores the role that climate plays in conifer establishment. (Again, California has been experiencing one of the most severe droughts in history.)

Many conifers only have good seed production every five to ten years. Even in a good cone crop year, seeds require very a precise combination of moisture, temperature, and soil for successful germination and then another set of factors for seedling survival. The likelihood that all these factors would be met in five years is not high. So, expecting plots to have conifer regeneration after such a short period ignores the reality of climatic and tree biology factors required for regeneration.

Furthermore, the researchers own data showed there was less conifer regeneration on drier sites — exactly what one would expect during a severe drought that only exacerbates seedling failures.

Another important value of high-severity blazes that was not mentioned in the report is that they introduce snags and dead wood into forest ecosystems. The post-fire snag forest is some of the rarest and shortest lived habitat in our forest ecosystems. Studies have demonstrated that such snag forests — which include patches of native fire-following shrubs, downed logs, colorful wildflowers, and dense pockets of natural conifer and oak regeneration — are among one of the most biodiverse forest ecosystems. These short-lived forests exist only for a few years until the regeneration process is complete and new trees start taking over the space.

There were other methodological issues with the study. For instance, each study plot was only 1/70 of an acre. Given the natural heterogeneity of wildfires that result in mosaic patch of high, medium, low severity and unburned, small plots are unlikely to capture the diversity of regeneration that might characterize a larger plot. The study authors even acknowledged that much of the variation in conifer regeneration was due to non-fire attributes like slope, aspect (north slopes are moister) elevation, and other abiotic conditions that influenced conifer regeneration.

In addition, they acknowledge later in their paper that perhaps the Forest Service standard for conifer regeneration is too high, especially since most areas that meet such standard require thinning at a later date to reduce forest density. A lower stocking rate requirement would mean more of their plots would meet the Forest Service standards.

What all of this demonstrates is that much of the “problem” is an artifact of the unrealistic Forest Service silvicultural standards both for the number of conifer seedlings expected on a patch of land within five years and the bias towards timber production that ignores the many ecological benefits of high-severity fires. Many studies show it takes 30 to 60 years after a high-severity blaze for forest regeneration to occur under natural conditions. So what’s the rush?

Rather than alarming, lack of conifer regeneration allows other vegetation its “moment in the sun” so to speak, and provides for a much more diverse forest ecosystem. It also may be an important factor that is creating less dense forests that will be better adapted to future and predicted climate warming.

George Wuerthner is an ecologist who has been studying predators for four decades. He serves on the Science Advisory Board of Project Coyote and is the author of 38 books including Welfare Ranching, Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy, Energy: The Delusion of Endless Growth and Overdevelopment, Thrillcraft, and Keeping the Wild.

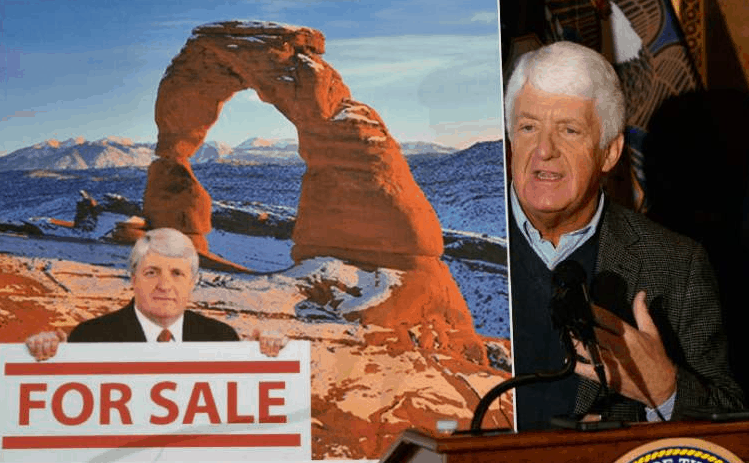

And on the first day of Congress, GOP makes it easier to sell off America’s public lands

The Washington Post has the full story. Unfortunately, the article doesn’t mention the fact that Montana Rep Ryan Zinke – Trump’s Interior Secretary nominee – also voted yes on this provision.

House Republicans, led by Utah’s Rep. Rob Bishop, are preparing to change the way Congress calculates the cost of transferring federal lands to the states and other entities, a move that would make it easier for members of the new Congress to cede federal control of public lands to state officials.

The provision, included as part as a larger rules package the House is slated to vote on this week, has attracted relatively little attention. But it highlights the extent to which some congressional Republicans hope to change the way public land is managed now that the GOP will control both the executive and legislative branch starting Jan. 20.

Under current Congressional Budget Office accounting rules, any transfer of federal land that generates revenue for the U.S. Treasury — whether through energy extraction, logging, grazing or other activities — has a cost. If lawmakers wanted to give land-generating receipts to a given state, local government or tribe, they would have to account for that loss in expected cash flow. If the federal government conveys land where there is no economic activity, such as wilderness, there is no estimated cost associated with it.

But House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Bishop, who backs the idea of providing state and local officials with greater control over federal land, has authored language in the new rules package saying any such transfers “shall not be considered as providing new budget authority, decreasing revenues, increasing mandatory spending or increasing outlays.”

Rep. Raul Grijalva, Ariz., the top Democrat on the Natural Resources Committee, sent a letter Tuesday to fellow Democrats urging them to oppose the rules package on the basis of that proposal.

“The House Republican plan to give away America’s public lands for free is outrageous and absurd,” Grijalva said in a statement. “This proposed rule change would make it easier to implement this plan by allowing the Congress to give away every single piece of property we own, for free, and pretend we have lost nothing of any value. Not only is this fiscally irresponsible, but it is also a flagrant attack on places and resources valued and beloved by the American people.”

“If California wants to secede, let it go”

Interesting viewpoint from High Country News….

If California wants to secede, let it go

By Robert H. Nelson/Writers on the Range

Many Californians woke up the night after the presidential election thinking that they were living in a different country. A few felt so alienated that they publicly raised the possibility of seceding from the United States.

There is no constitutional way, however, to do this. But there is a less radical step that would amount to a limited secession and would require only an act of Congress. Forty-five percent of the land in California is administered by the federal government — including 20 percent of the state in national forests and 15 percent under the Bureau of Land Management. Rather than outright secession, California could try to assert full state sovereignty over all this land.

Until Nov. 8, California wouldn’t have cared about this, but with the prospect of a Donald Trump administration soon managing almost half the land in the state, Californians may want to rethink their traditional stance. Otherwise, they are likely to face more oil and gas drilling, increased timber harvesting and intensive recreational use and development on federal land in the state.

Much of the rest of the West, moreover, might support their cause. In recent years, Utah has been actively seeking a large-scale transfer of federal lands. During the Obama years, Utah’s government has deeply resented the imposition of out-of-state values on the 65 percent of the state that is federally owned — just as California may now come to resent the outside imposition of new land management practices by a Trump administration.

Utah, ironically, may now see a comprehensive land transfer as less urgent. That has happened before: The election of President Reagan in 1980 took the steam out of the Sagebrush Rebellion in Utah and elsewhere in the West. In retrospect, however, that proved to be shortsighted, as future administrations reversed course and asserted even more authority over Western lands.

If California were to lead the charge, and with Trump as president, fundamental changes in the federal ownership of land in the West might become more politically feasible than ever before. There are additional strong arguments, moreover, for a transfer of federal lands (excluding national parks and military facilities) in the West to the states today. Over the region as a whole, the federal government owns almost 50 percent of the land, and higher percentages in many rural areas. When Washington, D.C., imposes policies and values that conflict with the majority views of the residents of whole states, the federal government, in effect, takes on the role of an occupying force. It may not be traditional colonialism, but there are resemblances.

Defenders of federal land management argue that the public lands belong to all Americans. Although advocates of a federal land transfer promise to keep the lands in state ownership, many Westerners fear that the states might privatize the lands outright or administer them for narrowly private interests. The implicit assumption in this is that there are core national values that should govern public-land management in all the Western states and that the federal government is best placed to advance these values. But the reality is that Americans are today deeply divided on many fundamental value questions — and these divisions are often geographically based.

Since at least the 1990s, many Westerners have become convinced that the management of federal lands in the West is dysfunctional no matter what party is in power. This should come as no surprise, since much of Washington itself is dysfunctional.

So I propose the following. Congress should enact a law allowing each state to call a referendum on the question: Do you want the federal government to transfer federal lands in your state (excluding national parks and military lands) to state ownership? If the vote is affirmative, a transfer would follow automatically. You might call it a Scotland solution, adapted to American circumstances.

California could pursue its preservationist values, while Utah could allow wider access to its new lands. With public-land management decentralized to the state level, where there would be greater basic agreement on ends and means, it might finally be possible to overcome the political paralysis of the current federal land management system centered in Washington.

So I say, let Californians decide if they want to secede, at least in this partial way, and the residents of other Western states as well.

Robert H. Nelson is a contributor to Writers on the Range, the opinion service of High Country News (hcn.org). He is a professor in the School of Public Policy of the University of Maryland, and from 1975 to 1993, worked for eight different secretaries of the Interior Department.

10,000 Square Miles: Montana Forests Testing Planning Reforms

Three National Forests, the Flathead, the Helena-Lewis and Clark and the Custer-Gallatin are all writing the basic governing documents that lay out what can and can’t happen, and where, in their vast territories. In January the Helena-Lewis and Clark is holding a series of public input meetings on their new forest plan.

Montana Public Radion interview with Martin Nie, University of Montana Professor of Natural Resource Policy.

10,000 Square Miles: Montana Forests Testing Planning Reforms

Interesting excerpt about potential new laws under the Trump administration:

Whitney: I guess the other option would be for Congress to write more specific laws, do you have concerns about that?

Nie: Oh, absolutely, and it’s a great question. I think that’s what we’re going to see in the next year, a big pivot point. We’ve seen a number of proposed bills that are really radical overhauls of the existing legal structure, in terms of NEPA, in terms of National Forest management, and so that’ll be the question. And I don’t know what to expect in that regard. We’re at such a pivotal crossroads with federal lands management. It goes even beyond the National Forests. We’ve just had one pendulum swing from another for the last 20 years. And you’ve seen our federal land agencies swing between administrations, and so yeah, I think planning does offer that potential of having a very grounded, place-specific sort of direction for an agency that has the potential of a lot of local and national buy-in.