SPOILER ALERT: The answer is clearcut.

Make sure to check out this latest piece of solid investigative journalism by Rob Davis of the Oregonian and Tony Schick, a reporter for Oregon Public Radio. Rob Davis is an investigative reporter covering the environment for The Oregonian/OregonLive. Meanwhile, Tony Schick is a reporter for OPB. He’s been covering the environment in his home state of Oregon for the past seven years.

This article covers so many issues we’ve discussed and debated here at The Smokey Wire over the past decade or so. I have to admit that It will be fun to watch the usual suspects and predictable timber industry apologists dance their way around this one. I’d encourage readers of The Smokey Wire to read the actual investigative piece for themselves and then compare what’s in the piece with the predicable comments that are sure to follow in the comment section below. Will people attack the reporters? Will people attack the people interviewed in the article? Will people gloss over the findings from the investigation? Will people offer any evidence or proof to refute the findings of this investigation? I guess we are about to find out.

UPDATE: Just saw this Action Alert from Oregon Wild, titled “Defund the Oregon Forest Resources Institute.” The FB post had this text with it: “Undermining science, threatening a journalism project, and coordinating logging lobby days with industry are just a few of the incidents uncovered in a new investigation of the Oregon Forest Resources Institute. It’s time to defund them.”

What Happened When a Public Institute Became a De Facto Lobbying Arm of the Timber Industry

Internal emails show a tax-funded agency created to educate people about forestry has acted as a public-relations agency and lobbying arm for Oregon’s timber industry, in some cases skirting legal constraints that forbid it from doing so.

by Rob Davis, The Oregonian/OregonLive, and Tony Schick, OPB, August 4, 2020

As Oregon Gov. Kate Brown crafted a bill in 2018 to enact sweeping limits on greenhouse gas emissions, leaders at an obscure state agency worked behind the scenes to discredit research they feared would persuade her to target one of the state’s most powerful industries.

The research, published that March, calculated for the first time how much carbon was lost to the atmosphere as a result of cutting trees in Oregon. It concluded that logging, once thought to have no negative effect on global warming, was among the state’s biggest climate polluters.

Researchers led by Oregon State University forest ecologist Beverly Law found that the state could dramatically shrink its carbon footprint if trees on private land were cut less frequently, a recommendation that pushed against the approach of Wall Street real estate trusts and investment funds that cut trees at a younger age to maximize profits.

The findings alarmed forest industry leaders in Oregon, who quickly assembled scientists and lobbyists to challenge the study and its authors. Among the groups leading the fight was the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, a quasi-governmental state agency funded with tax dollars that is, by law, restricted from influencing or attempting to influence policy.

Leaders at the institute worked behind the scenes for months to persuade lawmakers and the dean of Oregon State’s College of Forestry that the research was flawed, informing timber lobbyists of their efforts along the way, according to an investigation by The Oregonian/OregonLive, OPB and ProPublica.

The institute needs to “develop a swift, fairly immediate, response so that this study doesn’t drive all of the initial narrative and so that it doesn’t drive early attempts at the state level to develop carbon policy based on what appears to me to be faulty science,” Timm Locke, the agency’s forest products director at the time, wrote in a May 2018 email with the subject line “Bev Law carbon BS.” “One reason I feel this way is that the Governor’s office is noticing.”

Then, Locke, a public employee, offered to help a timber lobbyist draft a counterargument “those of us in the industry can use.”

The email is one of thousands obtained as part of an investigation by The Oregonian/OregonLive, OPB and ProPublica, which found that the Oregon Forest Resources Institute, created in the early 1990s to educate residents about forestry, has acted as a public-relations agency and lobbying arm for the timber industry, in some cases skirting legal constraints that forbid it from doing so.

Oregon’s biggest forest owners have eliminated thousands of jobs, shrinking their contribution to the state’s economy while receiving an estimated $3 billion in tax cuts since 1991, a June story that is part of the yearlong investigation by OPB, The Oregonian/OregonLive and ProPublica revealed. The timber industry has maintained outsized influence in the state, thwarting attempts to restrict logging with the help of a decades long public opinion campaign. And through the institute, the timber industry executed that campaign from behind the veneer of the state government.

The tax-funded institute spends $1 million annually on advertising that for years promoted Oregon’s logging laws as strong, even as many became weaker than in neighboring states, a review by the news organizations found. It worked to undercut university research, challenging the validity of studies and the credibility of professors. Its executive directors sat through private industry deliberations about dark money attack ads that opposed Brown’s 2018 reelection. And, in 2019, its board discussed rushing a report in an attempt to stop ballot measures that targeted logging, the news organizations found.

Erin Isselmann, the institute’s executive director since July 2018, defended the agency. Isselmann said she has operated “under the highest ethical standards.” After the news organizations obtained the emails, Isselmann told board members she had solicited an opinion from the Oregon Department of Justice about the institute’s legal constraints. She declined to make it public, citing attorney-client privilege.

Locke said in an interview that the line between lobbying and educating at the institute was unclear. He said his pushback against Law’s study wasn’t an attempt to sway Brown’s carbon policy, “so much as to ensure that the policy was based on sound information.”

Charles Boyle, a spokesman for the governor, called the news organizations’ findings “deeply troubling.” He said they merited “at the very least an investigation by the Oregon Government Ethics Commission or the secretary of state’s office, and perhaps an audit to bring more facts to light.”

“It is clear that they have openly disregarded the idea that OFRI is a public entity that should serve the interests of Oregonians,” Boyle said.

The institute, created by state lawmakers in 1991, was granted the ability to support the timber industry by educating the public about forests and wood products, and by helping private landowners manage their forests in ways that protect the environment.

But the law bars the institute from attempting to influence the actions of any other state agency, which could make the pushback against the Oregon State University study a violation, said William Funk, an emeritus law professor at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland.

“Even if lawful, it’s just wrong,” Funk said. “The academy should rule itself. It should not be strong-armed by industry in league with a government agency.”

After the carbon study was released, Paul Barnum, who served as the institute’s executive director at the time, told representatives of a national trade group, the American Wood Council, that he would work with state lobbyists to respond, calling the research “of grave concern to all of us in Oregon.”

“These are folks who likely believe that the planet would be better off without humans,” Barnum wrote in a May 2018 email.

Barnum offered to use the institute’s press release distribution service to circulate an analysis written by a former U.S. Forest Service employee who ran an online publication partly funded by timber industry groups. The analysis claimed the study underestimated emissions from wildfires and didn’t account for increased logging in other states or countries if Oregon cut fewer trees.

He also sent the analysis to a Republican state representative who was a supporter of the timber industry and later became vice chairman of the legislative committee negotiating the governor’s climate bill. In his email, Barnum said the analysis refuted the Oregon State University research, which had undergone peer review from fellow scientists. He later emailed the dean of Law’s college, objecting to a scheduled public radio appearance of hers.

“That’s not the way science works,” Law said in an interview. “It’s attacking academic freedom.”

Barnum, who retired as executive director in 2018 but continued working under contract through June, said it was not wrong for him to question the Oregon State University study or any other academic research. But he acknowledged making inappropriate comments, including some that questioned the researchers’ motives.

“My comments demeaned me, and more importantly, the organization I professed to represent,” Barnum said. “I regret my words and offer sincere apologies to those I discredited.”

“Too Sophisticated to Be Fooled by Propaganda”

Reeling from protests and lawsuits over cutting trees that were hundreds of years old, the state’s largest timber lobbying group in 1991 asked for help selling the benefits of forestry to Oregonians.

A year earlier, federal protections for the northern spotted owl had suddenly put millions of acres of Oregon’s national forests off-limits to logging.

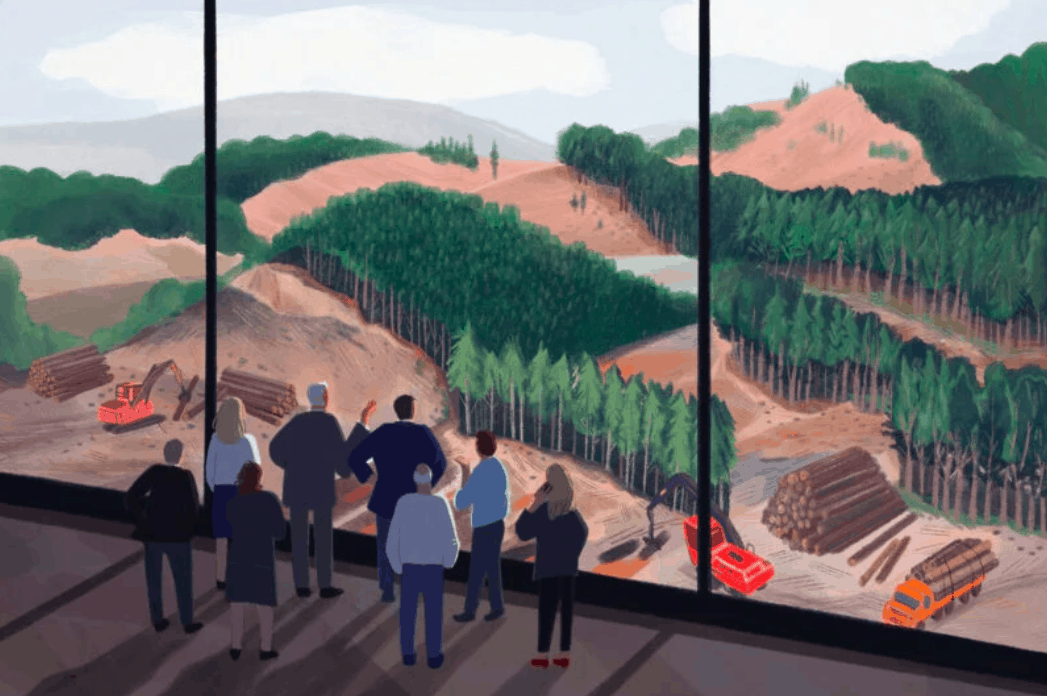

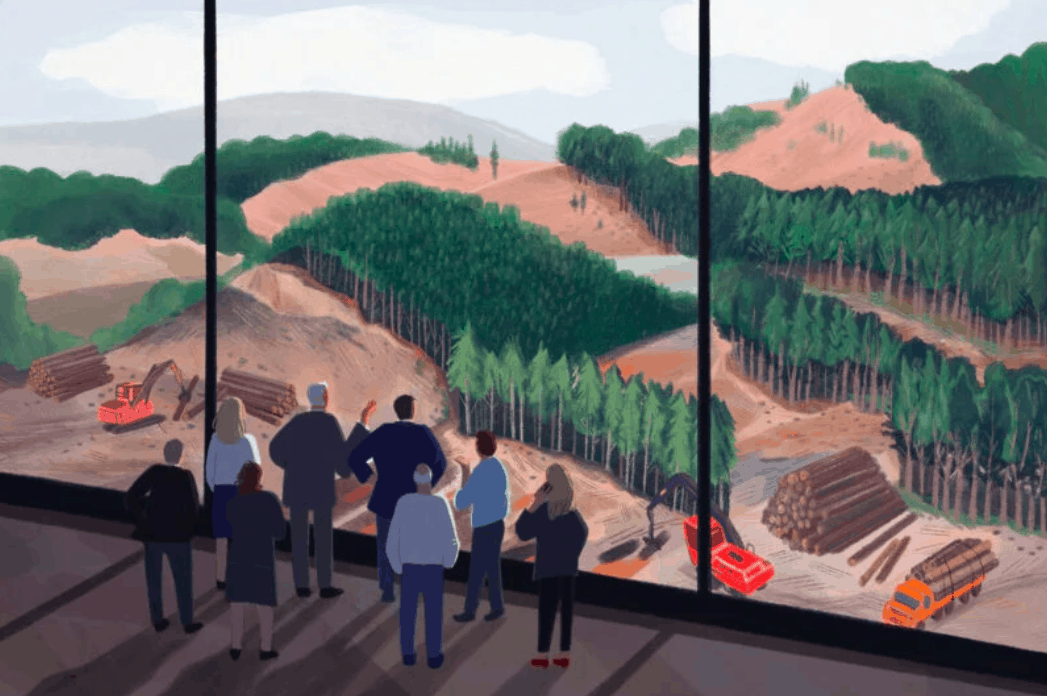

With national news showing images of vast stretches of ancient forests that had been clear-cut, a practice in which thousands of trees are leveled at once, representatives of Oregon’s biggest timber companies attended a hearing in the state Capitol. They urged lawmakers to create an agency that would provide credible public education based on documented facts and reliable science.

The proposed agency would not rely “on wishful myths and clever slogans,” said John Hampton, then president of the Oregon Forest & Industries Council, an association representing the state’s biggest timber owners and manufacturers.

“There are those who have asked, why should the state sanction a propaganda machine for the forest industries?” Hampton told lawmakers in 1991. “The answer is, the people of Oregon are too sophisticated to be fooled by propaganda and, frankly, people like me who will pay for this program would not stand for it.”

That year, the state’s Legislature approved the creation of the Oregon Forest Resources Institute.

As lawmakers raised taxes on logging to fund the institute, they cut millions of dollars in taxes that timber owners paid to fund schools and county governments. They also gave control of the institute’s tax rate to its board.

Today, with an annual budget of about $4 million, the institute creates television, radio and digital advertising campaigns, educational materials for classrooms, reports, workshops and illustrated manuals. It describes itself as “a centralized gateway of shared ideas and collaborative dialogue.”

The line between the timber industry’s lobbying work and the institute’s actions has often been blurred.

Many of the companies represented on the institute’s board are also members of the Oregon Forest & Industries Council, the industry’s primary lobbying group, according to the trade association’s website and tax filings.

Lawmakers gave timber companies control of the institute with nine of the 11 voting board seats. The other two voting positions are a small forest landowner and a representative for timber workers. The board also has one public member who cannot vote and is prohibited from belonging to an environmental advocacy group. The position has been vacant for all but a month since the January 2019 resignation of Chris Edwards, a former state senator who became a lobbyist for the timber industry.

Emails show institute employees routinely participated in the industry council’s public affairs and legislative strategy meetings. At one, Barnum and Isselmann got a sneak peek at political attack ads against Brown from Priority Oregon, a business group that opposed her reelection in 2018. Acknowledging in an interview that it was inappropriate, Barnum said they should have left.

Public employees at the institute helped timber industry groups plan a lobbying day at the state capitol, then asked the lobbyists not to include the institute’s name as a sponsor on the agenda, suggesting that they did not want the institute listed as a group that advocates with legislators.

They also coordinated a demonstration of aerial pesticide spraying and invited elected officials, singling out for special attention a lawmaker who’d tried to tighten spraying rules.

A spokeswoman for the timber industry council didn’t respond to specific questions about its relationship with the institute. Instead, she sent a statement praising the institute for 30 years of providing “valuable, foundational public understanding of one of our state’s greatest resources and cornerstone industries.”

The institute operates in near anonymity. Its own surveys show that few who see its advertisements remember who’s behind them.

In 2018, a potential recruit to lead the institute asked whether its board was open to new approaches. Barnum responded in an email, cautioning that there were limits to how much change would be tolerated.

Large industrial landowners provide roughly 75% to 80% of the institute’s funding, Barnum told the recruit.

“You can’t get too far ahead of those who pay the majority of the tax,” Barnum wrote, “at least not if you want to stay employed.”

“That’s Not the Way Science Works”

Hours before Beverly Law was scheduled to be interviewed on a Southern Oregon public radio station to discuss her research in June 2018, the dean of the Oregon State College of Forestry, Anthony Davis, received an email from Barnum suggesting her study was built on faulty assumptions.

“I understand academic freedom,” he told Davis in an email. But given criticisms from industry scientists and a timber-backed publication, “this seems like policy advocacy based on a heavily flawed study.”

In an interview, Barnum said the institute got involved because “historically, we have not felt it our role to be silent when we believe research to be biased, nonobjective or opaque.” He demurred when asked to identify mistakes in the report.

He said he was not trying to keep Law from appearing on Jefferson Public Radio. “I just was drawing it to his attention,” he said.

The suggestion that the study was flawed was nothing less than an attempt to stifle research, said William Schlesinger, the former dean of the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. Schlesinger led the study’s peer review as an editor for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which published the work.

“That’s one of the most stringent journals in the world,” Schlesinger said. The fact the scientists “were able to put together an analysis that survived the scrutiny of peer review speaks strongly to how solid that work is.”

Barnum continued criticizing Law’s research, sending a draft of a letter from the institute’s board to Davis on July 6, 2018, requesting that he quickly commission a separate review because “unfortunately, media and policymakers are already using the Law et. al. study to promote anti-logging agendas.”

Davis responded later that day to tell Barnum it would be inappropriate for him to comment on a draft letter.

“I was confident in the findings of the researchers and of the process used to publish the paper, which follows the process used by scientists all around the country and the world,” Davis said in an interview.

Barnum eventually withdrew the letter. Not because it upset the academics at Oregon State, but because the Oregon Forest & Industries Council’s executive director, Kristina McNitt, was displeased, telling Barnum she was “shocked” he forwarded the draft to the university without her group’s approval.

In another case, the institute spent multiple years discussing a response to a forthcoming study with potentially negative effects on industry, even as Barnum privately acknowledged the validity of the research.

Mark Needham, a professor in Oregon State’s forestry school, began planning a survey in 2017 to gauge public perceptions of herbicide spraying in private forests. Timber companies apply herbicides from helicopters to kill vegetation that sprouts in the bare earth of clear-cuts and competes for water and sunlight with newly planted tree seedlings.

Needham’s survey included questions about whether residents trusted private timber companies to provide truthful information about the issue and whether they would vote for or against aerial spraying if asked at the ballot.

Internal research by the timber industry has shown Oregonians are worried about the practice, which has become increasingly common as the state’s forests have been logged more frequently.

“The research project sounds legit, but also fairly dangerous,” Barnum wrote in a July 19, 2017, email. “We already know what the public perception about chemical use is, so to have something in the public domain, especially from the College of Forestry, that confirms it, would not be a good thing in my estimation.”

The survey was eventually distributed to more than 5,000 Oregon households in April 2019. Two months later, after a timber company alerted the institute about the survey progress, Isselmann emailed Davis, the forestry school’s dean, challenging the validity of the questions.

In a separate email to a timber executive, Isselmann said most peer-reviewed journals wouldn’t accept survey results unless they were high enough quality, but that “none of this will stop the researchers from promoting their work with the media and in OSU publications. I think we need to be prepared for this outcome and start now to educate policy makers and other influencers about the reliability and validity of survey research.”

She suggested in the email that the institute could prepare for the results by spending $60,000 on its own study.

“I don’t think my actions indicate that I was attacking science, and I think my actions reflect that I wanted to learn more about the survey and how its results would be used,” Isselmann said in an interview. The institute has not conducted its own survey, she said, and has no plans to.

Needham said that his survey responses are still being analyzed, and that Isselmann was incorrect to suggest the questions might be invalid.

“I live and die by the university’s tenets of academic freedom and the external scientific peer-review process,” Needham said. “It’ll be rigorous peer review, conducted by respected scientific journals in our field, that will judge the methods and results of our study.”

When professors at the University of Oregon produced a video critical of logging during a research project, the institute tried to kill the work. Barnum helped lead the pushback in May 2017.

As part of a study on how new 360-degree virtual reality videos affected viewer behavior, students and professors created a video for an environmental group that urged people to join the fight to update Oregon’s logging laws. Strategic communications professor Donna Davis, who studies virtual reality, wanted to know whether an immersive video would make viewers more likely to participate in a cause.

Objecting to the involvement of journalism professor Wes Pope in the video’s creation, Barnum joined a contingent of industry lawyers and lobbyists who alerted timber executives on the university’s board of trustees about the research, then met with school officials and threatened to pull timber donor funding if the university didn’t “extricate” itself from the project.

Barnum said the institute got involved because he saw it as an advocacy project using the university to disseminate negative information about forest practices.

Pope said the university allowed him and his colleagues to continue their work. But the professors, who lacked tenure, let it die. In part, Pope said they said they were worried about angering the timber industry.

“If anybody’s doing anything that possibly threatens or questions logging practices in the state of Oregon, they’re going to swoop in and crush that message really quickly and really thoroughly,” said Pope, now tenured.

Muddying the Waters

In 2013, residents in the tiny coastal town of Rockaway Beach received alerts about cancer-causing contamination in their drinking water after timber companies logged most of the hills around the creek that supplies the town.

The same year, state health officials released a study about the communities around Triangle Lake in Oregon’s Coast Range, the dominant timber-producing region, which found low levels of toxic herbicides in the drinking water, air and in residents’ urine. The state said it was possible timber spraying was the source. Residents in the area called for statewide restrictions on spraying within 2 miles of schools and homes, a request that reached then-Gov. John Kitzhaber’s office, though he didn’t grant it.

Pete Sikora, CEO of Giustina Resources, a large timber company operating in the same county, emailed Barnum to urge him to pay attention to the issue.

“I think drinking water is going to be our biggest public perception issue,” Sikora told Barnum. “As you know public perception often leads to public policy.”

Tens of thousands of residents in towns throughout Oregon’s heavily logged coastal mountains draw their drinking water from industrial forests. Industrial clear-cutting can reduce both the quality and quantity of drinking water, according to state regulators and recent research from Oregon State University.

For years, the institute has helped timber executives who worried about the threat that new drinking water protections would pose to their ability to log. The message that Oregon’s forests produced clean water was a central theme.

Two months after Sikora’s email, a commercial was released featuring two loggers, a father and son, standing creekside in a forest and pouring a glass of crystal clear water.

“This is Oregon water,” says the father, a third-generation logger.

“Oregon has strong laws that help protect our watersheds,” he says. “And besides, it’s the right thing to do.”

“You’ve got to have clean water,” his son says.

The commercial is part of the institute’s advertising campaign, which over the years has grown to be its single largest expenditure at $1 million annually. The campaign has reached Oregonians more than 300 million times since 2013, according to institute documents, with a key message: Oregonians live in a state with strong logging laws.

The commercials don’t acknowledge significant problems caused by industrial logging. The federal government withholds more than $1 million from Oregon each year because its laws don’t do enough to protect coastal rivers from logging pollution. Federal regulators have also faulted Oregon’s logging laws for pushing coastal salmon populations toward extinction.

“There’s only so many messages you can get into in a 30-second commercial,” Isselmann said. “We use the medium of television advertising to educate the public generally, and we direct them to our website and all of our materials if they would like to take a deeper dive and learn more information.”

Records show the institute’s employees have avoided publishing information on the website that could make Oregon’s laws look inadequate.

In 2016, a new employee, Inka Bajandas, faced resistance when she suggested writing a blog post comparing Oregon’s logging laws with California and Washington. Bajandas, the institute’s public outreach manager, told other institute leaders she wanted to address concerns that forest protection laws in Oregon were weaker than in other West Coast states.

“I’m also just genuinely curious about this,” she wrote.

Locke, who no longer works for the institute, told Bajandas that he believed the comparison was a bad idea.

“Certain elements (some that enviros think are most important)” of Oregon’s logging laws, he said, “are not quite as strong” as in Washington or California.

If his understanding was correct, Locke said, “then comparing the three could be a slippery slope. It’s not really about having the absolutely most stringent laws there are.”

Barnum, the institute’s director at the time, responded that Locke was “right on” with his response.

“We do not want to promote a regulatory ‘arms race’ among the three western states, which is where the enviros would like to take us,” Barnum wrote.

Asked about the exchange, Bajandas said the emails speak for themselves but don’t reflect the institute’s current management. Under Isselmann’s leadership, the institute has removed the phrase “strong laws” from advertisements, instead saying that forests are managed responsibly and protect drinking water.

“Because I don’t think a law is something that you can quantify,” Isselmann said. “It’s a fact. You either have a law or you don’t have a law.”

As lawmakers and environmental groups continued to press the issue of water protections, the institute spent $120,000 for Oregon State researchers to study the connections between logging and drinking water contamination.

In November 2019, with a ballot box fight looming over Oregon’s logging practices, the institute’s board discussed whether to speed up the release of the study.

Frustrated by years of legislative inaction, environmental advocates had proposed ballot measures to increase protections for communities that drew their drinking water from forests.

Oregon State’s report, which the institute initially hoped to time for the 2019 Legislature, was a year overdue.

Citing the ballot measures, Casey Roscoe, a board member and executive with Seneca Jones Timber Co., one of Oregon’s biggest logging companies, suggested accelerating the research during a public meeting, on a conference call that happened with nearly no one else outside the organization listening.

“I get if it’s not ready for prime time, but will people be able to access it in order to use that science in conversations and so forth?” Roscoe asked.

“Sometimes, you can stop things before they start,” Roscoe told board members.

Roscoe, whose company gave more than $100,000 to the industry campaign against the measures, said in an interview that she wanted both sides to have the best information available.

Timber companies and environmental advocates ultimately struck an agreement in February to negotiate new logging rules, eliminating the urgency for a report that could help contest ballot measures.

In June, the institute released a draft of the Oregon State study along with its own summary of the scientists’ work. The institute hired Barnum to write the 24-page summary, which downplays some of the more critical aspects of the 321-page study.

The science review says Oregon’s forest practices laws are insufficient to protect some aspects of water quality. It highlights survey results in which dozens of municipal drinking water providers in Oregon said logging was their biggest concern.

It concludes with a list of recommendations, including changes to the state’s logging laws, mandatory reporting of chemical use in forests, increased pesticide sampling and more tree buffers along small streams to prevent chemicals from getting into the water.

The institute’s summary, however, focuses on how forests provide higher-quality water than cities or farms.

It makes no mention of deficiencies in Oregon’s logging laws and says they “help safeguard drinking water sources.”

It doesn’t list any of the scientists’ recommendations. Instead, it ends by saying: “As Oregonians in 2020, this is where we find ourselves: with high-quality water, significantly improved forest practices and the ability to continue improving. And that, I believe, is worth a toast, not only to our forests that supply the raw water, but to those who keep the water safe – from trees to tap.”

“Why Wouldn’t You Want to Know What the Science Is Saying?”

A year after the Oregon State University carbon study was published, the climate bill that had worried the institute came before the state Legislature.

It was 2019, and Democrats had gained a supermajority in both chambers, promising to make Oregon the second state in the nation behind California with a cap on carbon emissions by targeting pollution from fuel consumption and manufacturing. Republicans said they’d do everything they could to stop the bill.

Law, the lead researcher, said she heard state senators citing not her study, but the talking points undermining it that the institute had circulated months before.

“That’s unfortunate because honestly, really, why wouldn’t you want to know what the science is saying?” Law said.

The industry had been concerned that Law’s study would prompt the governor to target logging in the climate bill. But she and lawmakers not only excluded logging, they added an amendment to ensure the measure would avoid any reductions in logging.

The bill died after 11 Senate Republicans walked out of the capitol and went into hiding, denying Democrats the quorum they needed for passage.

The institute was absent during the carbon debate. Its leaders were defending their budget from a longtime Democratic lawmaker, state Rep. Paul Holvey, who said the institute’s advertisements were a disturbing use of money that could be better spent fighting wildfires. His bill died after the timber industry opposed defunding the institute. Rather than shrinking by 60% as Holvey had proposed, the institute’s budget grew after its board approved an increase in logging taxes that spring.

Oregon State’s forestry college also wanted an increase to fund new research. But the lawmakers kept the college’s funding flat after the timber industry opposed the increase.

By the time the Legislature adjourned, the institute had begun its own research report to study carbon in Oregon’s forests.

To write it, the institute recruited the same consultant that industry lobbyists used to refute Law’s study.