Many thanks to Jon for finding and linking to this interesting document that describes the Mexican Spotted Owl Leadership Forum notes. First.. who’s at the table. Looks like CBD, the FS, the USFWS, representatives of Eastern Arizona counties, timber industry, and I’m not sure of the affiliation of the others. Maybe this is “the room where it happens,” in terms of decisions being made, in the words of the Hamilton musical. The group identified some “systemic issues.” I picked the first 13 to post here. Some of them sound very familiar from other NEPA and collaborative discussions. It’s not clear how much of that is due to the use of CBM (or condition-based management). My comments and questions are in bold.

The “Systemic Issues” section identifies issues to be addressed to prevent future projects from being challenged. Critical among others:

1. There is a disconnect between the broader scope public documents readily available for review and what actually happens on the ground during implementation. (<em>I’m not sure whether this is a contracting/marking kind of problem, or related to CBM, or ???).

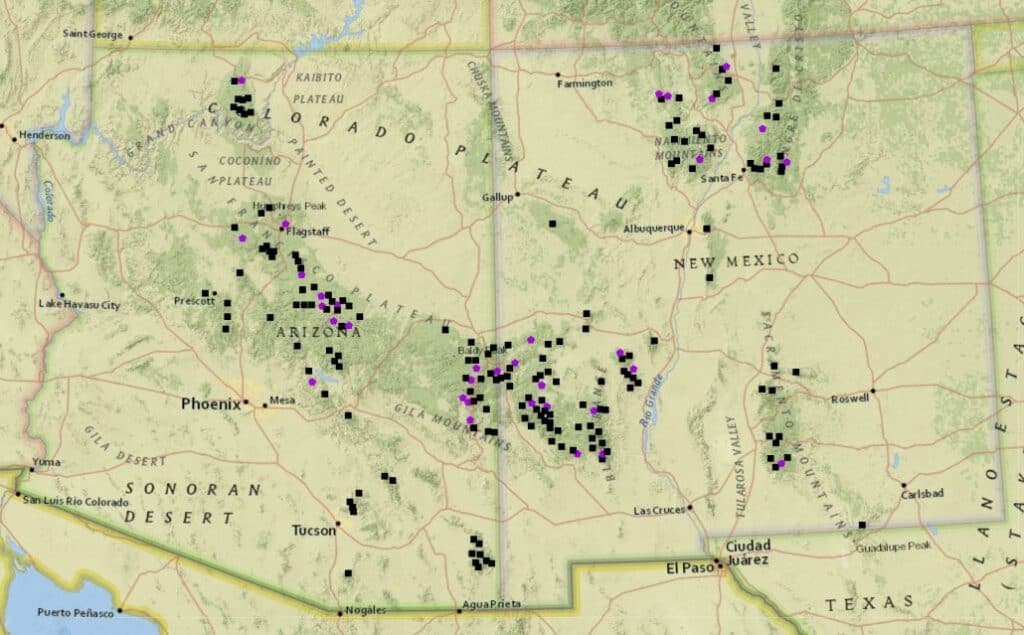

2. Site specific MSO field data necessary to select Recovery Plan recommended treatments is generally not available prior to NEPA analyses. This is likely due to cost constraints, workforce limitations and slow pace of technology deployment (e.g. LiDAR) at a time of accelerated landscape scale restoration. (I wonder whether this matters if the field data is developed prior to design of projects?)

3. Consistent/standardized templates across projects are not used for data analysis and presentation. (The idea of templates has been popular with NEPA improvement efforts for years, but has met with resistance from (some) practitioners. This group has a good point IMHO, that individuality and creativity by each unit works for many things, but perhaps not when folks are trying to implement projects across ownerships at the landscape scale.)

4. Data requirement interpretation varies across project (e.g. post treatment data inclusive or not of post treatment fire).

5. Generally, the NEPA process does not analyze actual stand treatments for the MSO projects but broad ranges of allowable treatments. Actual treatments are decided during field trips prior to project implementation. NEPA analyzes actions at a broad scale and in some cases (e.g. Hassayampa) appears insufficient.

6. Project level documents such as BA, BO, stand inventories, etc. are difficult for the public to access; and data that should be readily available such as project shapefiles are near impossible to obtain. Further, interagency documentations of changes are generally not accessible to the public. Such documents are, with very few exceptions, public documents that must be made available to the public. There is no ‘one-stop-shop’ location for documentation of specific projects. (This seems relatively easy to do on the FS site for the project..at the same time for many projects in many parts of the country, there is not this level of interest (e.g. shapefiles) by most of “the public”).

7. Documents tiering across agencies (from USFS to USFWS) and processes (from NEPA to consultation to implementation), combined with difficult documents access complicates

public understanding of treatments and monitoring that are implemented. For example, one project referring to another project’s monitoring plan is confusing to those not familiar with the other project.8. Monitoring as a reasonable and prudent measure often lacks clarity and specificity at the NEPA stage and the final plan is not always appended to the BO.

9. There is no clear tool or method in place to account for the cumulative effect across various projects’ actual treatments, and to reconcile the distribution of treatments along the spectrum of intensities (including no treatment) within the landscape, as recommended in the Recovery Plan, to establish an environmental baseline among neighboring projects. (I don’t really understand what this would look like “reconcile the distribution of treatments”? but it’s probably clear in the Recovery Plan).

10. The current management practice of relying on post NEPA field trips by a few select individuals to decide upon actual treatments is not scalable to landscape scale restoration.(This probably is also relevant to other CBM protocols, we’ve discussed this about programmatic kinds of CE’s).

11. Current MSO management appears to be a precursor of the proposed general “Condition Based Management” (CBM) in the on-going NEPA Revision. Lessons learned in the MSO Workshop are likely applicable to CBM at-large, as relates to communicating to the public the treatments and monitoring that are actually implemented.

12. The lack of succession plans and depth of bench for critical resource personnel with unique projects knowledge, compromises the robustness of the USFS and USFWS processes. (I just ran across an old NEPA review in my files that said access to specialists was a problem (at least for one forest, about 20 years ago).

13. A workshop or series of workshops is needed to address the systemic issues.