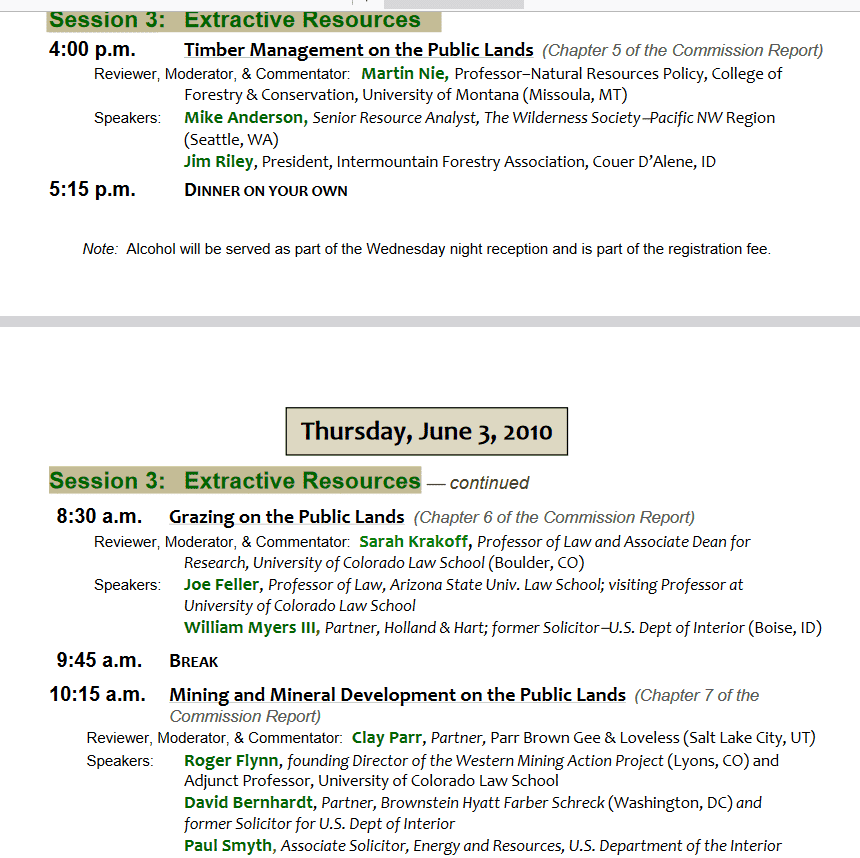

Just a friendly reminder of TSW’s mission:

Dan Farber Weighs in on NEPA Permitting Reform

We had a good discussion here with LM and Jon, but I thought I’d post this one.

UPDATE: I heard back from Dan Farber on the “do these changes apply to NEPA for everything” question.. here is what he said.

So far as I can tell, the NEPA-related provisions are all amendments to NEPA itself and aren’t limited to particular types of projects. Most of the changes seem pretty consistent, however, with caselaw and CEQ regs. So except in a few places, I don’t think they’re going to have substantive impact. The deadlines, page limits, and lead-agency requirements may make a difference at the operational level, however.

Here’s Dan Farber of Berkeley Law’s take .. he seems pretty level-headed on this, which is perhaps to say, I tend to agree with him :).

The original version of NEPA is very brief. It lacks definitions or any indication of the process to be used in deciding whether a project requires an impact statement. Over the years, those gaps have been filled in by a combination of court decisions and guidelines from the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in the White House. In general, the FRA version of the Builder Act writes in the statute the rules worked out by courts and the CEQ.

There are some exceptions, however, where the changes may be more significant. Here are some significant changes that have been identified in discussions by legal scholars:

Extraterritoriality: No environmental review is required for actions or decisions with impacts entirely outside the U.S., such as funding a dam in another country. This appears to be a more rigid standard than courts have applied.

A somewhat more restrictive rule about how much control a federal agency has to have over a project before an environmental review is required.

A government agency considering a project can outsource preparation of the environmental review documents to the project sponsor, though the agency is required to exercise oversight. In practice, this would mean having the project sponsor pay for an independent consulting firm to do the work.

Page limits 150 or 300 pages depending on complexity and deadlines (2 years) for environmental impact statements. (Who uses page limits anymore instead of word counts?) One effect could be to discourage the use of graphics and maps that might actually make the statement much more understandable to the public.

Providing for appointment of a lead agency to be responsible for the impact statement when multiple agencies have jurisdiction over parts of the project. This is probably a good idea, but probably could have been implemented administratively even without a statute.

…..

How significant are the NEPA changes?

On the one hand, the NEPA provisions of the FRA seems fairly innocuous, and it may be helpful to have the rules clarified by statute. That provides a clear anchor point for judicial decisions and puts some limits on how much particular presidential administrations can play games with the statute. Thus, putting the rules into statutory form provides a bit of protection against the likes of Trump or Alito trying to gut longstanding practices.

SF- One person’s “playing games with the statute” or “gut longstanding practices” could be another’s “clarifying” such as BLM’s proposed rule and MUSYA. It’s all in your perspective..

On the other hand, it’s not clear how much the NEPA changes will actually speed up permitting. Deadlines for agencies to act sound good but experience has shown they’re very hard to enforce. The page limit is meaningless, since all the extra stuff will just go into the appendices.

In terms of speeding up permitting, the most promising change may be the ability to get applicants to pay for outside experts to draft the impact statement. The environmental review process is often slow simply because agencies don’t have the budget or staff to get it done faster. Outsourcing could really speed things up, but it will be crucial for agencies to exercise serious oversight. Otherwise, companies will find friendly consultants to paper over any environmental problems.

Overall, the NEPA provisions don’t seem to pose major problems. Or at least, none that we’ve been able to find so far. From an environmental perspective, that’s probably about the best we could expect from the fraught negotiations over the debt ceiling.

****************

My thoughts..

It seems like agency NEPA practitioners were not involved in many of these policy discussions. Wouldn’t they be the first people you would ask for ideas? Oh well.

I agree with Dan that page limits are pretty meaningless.

Don’t we already have the ability to have applicants pay for NEPA? I seem to remember a project (I’m sure Mike remembers) I used to call “Reasonable Access for Unreasonable People” with TetraTech as the contractor. In my mind, and with decades of experience, it’s much easier and less time-consuming to review someone else’s work than to do the initial work yourself. As long as the agency calls the shots on analysis, that should be the determining factor. As I recall, the applicant was not allowed to communicate directly with the contractor.. anyway perhaps someone out there has more experience. My point being 1) maybe that’s not as new as some people think and 2) maybe there are different ways of doing it, some that have worked out better than others.

It’s great to make a lead agency more accountable, if that would actually work.. except that when agencies disagree.. will only the lead agency have skin in the game?

It continues to sound as if these NEPA changes are more general than just energy projects, so I’m trying to find out more.

It also seems to me like OGC and FS NEPA folks have generated something on “what this means for the FS” which would be much better than my ramblings.. so if you run across this, please email me.

Finally.. a bit of cross-agency context.. one agency of DOI, the BOEM, used an EA for a 30 million acre swath of the Gulf of Mexico for wind energy, according to Greenwire.

House Bill and Permitting Reform

Anyone not doing something more enjoyable this weekend might want to take a look at this draft House Bill, specifically for us, “permitting reform”. I couldn’t spend much time on it.. but my first take was 1) it isn’t specific to energy permitting (could be wrong, so many clauses, so little time!) and 2) it’s mostly about getting federal agency practitioners to speed up- not so much about other sources of possible slowness, and 3)

‘SEC. 106. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINATION OF LEVEL OF

11 REVIEW.

12 ‘‘(a) THRESHOLD DETERMINATIONS.—An agency is

13 not required to prepare an environmental document with

14 respect to a proposed agency action if—

15 ‘‘(1) the proposed agency action is not a final

16 agency action within the meaning of such term in

17 chapter 5 of title 5, United States Code;

I wonder whether that might apply to NFMA plans. Hopefully someone will have time to take a gander at all this. Maybe so much has been negotiated that the changes are relatively meaningless (other than shortening NEPA docs and accountability for timelines). I’d appreciate others’ thoughts on this (plus links to others’ analyses).

Questions for Legal Folks on the Fire Retardant Order

Here’s (5-26-2023) a link to the order.. the FS has to work with the EPA and apparently needs to check in with the judge regularly as to how it’s progressing.

Some people have asked questions, to which I do not know the answer. I know that there are highly knowledgeable people (including a/the plaintiff) so hopefully we can get all our questions answered.

1. This is a Forest Service case, so it doesn’t seem to apply to BLM or other federal lands (?). Is it the airplane or the landowner that controls? So States with airplanes/retardant don’t need permits? Or perhaps they will also be incorporated somehow in the new permitting process (if they want to be?). And shared resources over interlocking ownerships (common in many places) sounds like the Nightmare on Checkerboard Street.

2. The ruling only applies to some states (Oregon, California, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and Alaska) also,apparently not Washington nor Utah, and none of the Eastern, Midwestern or Southern states. It seems like this would be very difficult for the FS to keep track of. Perhaps this is an example of lawsuits don’t always lead to coherent policy outcomes.

3. Since some of these releases are accidental, will the EPA just estimate how many accidents have been happening and permit that.. or require some kind of compensatory mitigation? Will the proposed Fed/State regulatory approach be subject to rulemaking and public comment? Or is that all unknown at this point?

4. Mr. Wuerthner’s declaration seems important. Is this the “usual suspect” Wuerthner? Does someone have a copy of his declaration? It might be interesting.

Here are a few paragraphs about the injunction:

FSEEE has not offered sufficient evidence on the hardships to the parties and has failed to demonstrate that the public interest would not be disserved by a permanent injunction. The USFS explains that the 213 recorded intrusions only occurred where it was necessary “to protect human life or public safety (23intrusions) or due to accident (190 intrusions).” (Doc. 12 at 9.) Although the injunction would presumably allow the USFS to continue to aerially deploy fire retardant, it is unclear how the agency would proceed or if the agency could completely avoid future CWA violations. Thus, the requested injunction could conceivably result in greater harm from wildfires—including to human life and property and to the environment—by preventing the USFS from effectively utilizing one of its fire fighting tools.

Although FSEEE claims that fire retardant is an ineffective tool in fighting wildfires, (Doc. 24 at 9), this fact is disputed, (see Docs. 8-1, 8-2). Additionally, although FSEEE has presented possible solutions that would allow continued use of retardant while reducing accidental discharges, such as a 600-foot buffer requirement, (Doc. 24 at 10), it has failed to demonstrate that such solutions would

actually be effective from either parties’ perspective. Moreover, FSEEE has not addressed how the injunction would be enforced, which would itself create a significant burden for both parties.

And of course both the FS and EPA have many other things on their plates- and tell us they are overwhelmed by work and are having trouble hiring people.. in the FS’s case actually fighting fires, spending IRA and BIL money, and battling the climate emergency while writing MOG rules and plan revisions.I’ve described the EPA lack of capacity and the bipartisan bill here. This would be an idea place for the separation of powers to kick in, IMHO.

A Paean to Skepticism I: Where the “Wood-Wide Web” Narrative Went Wrong

This is a great story of the science-journalism interface and how things can go wrong, even when everyone has the best of intentions. What I like is that the scientists admit to their own biases and perhaps a bit of overenthusiasm.. Skepticism by all of us.. is so important! This is the theme of the next three posts.

This is a great story of the science-journalism interface and how things can go wrong, even when everyone has the best of intentions. What I like is that the scientists admit to their own biases and perhaps a bit of overenthusiasm.. Skepticism by all of us.. is so important! This is the theme of the next three posts.

**************************

A compelling story about how forest fungal networks communicate has garnered much public interest. Is any of it true?

BY MELANIE JONES, JASON HOEKSEMA, & JUSTINE KARST 05.25.2023

Over the past few years, a fascinating narrative about forests and fungi has captured the public imagination. It holds that the roots of neighboring trees can be connected by fungal filaments, forming massive underground networks that can span entire forests — a so-called wood-wide web. Through this web, the story goes, trees share carbon, water, and other nutrients, and even send chemical warnings of dangers such as insect attacks. The narrative — recounted in books, podcasts, TV series, documentaries, and news articles — has prompted some experts to rethink not only forest management but the relationships between self-interest and altruism in human society.

But is any of it true?

The three of us have studied forest fungi for our whole careers, and even we were surprised by some of the more extraordinary claims surfacing in the media about the wood-wide web. Thinking we had missed something, we thoroughly reviewed 26 field studies, including several of our own, that looked at the role fungal networks play in resource transfer in forests. What we found shows how easily confirmation bias, unchecked claims, and credulous news reporting can, over time, distort research findings beyond recognition. It should serve as a cautionary tale for scientists and journalists alike.

First, let’s be clear: Fungi do grow inside and on tree roots, forming a symbiosis called a mycorrhiza, or fungus-root. Mycorrhizae are essential for the normal growth of trees. Among other things, the fungi can take up from the soil, and transfer to the tree, nutrients that roots could not otherwise access. In return, fungi receive from the roots sugars they need to grow.

As fungal filaments spread out through forest soil, they will often, at least temporarily, physically connect the roots of two neighboring trees. The resulting system of interconnected tree roots is called a common mycorrhizal network, or CMN.

Years ago, when the early experiments were being done on forest fungi, some of us — the authors of this essay included — simply got caught up in the excitement of a new idea.

When people speak of the wood-wide web, they are generally referring to CMNs. But there’s very little that scientists can say with certainty about how, and to what extent, trees interact via CMNs. Unfortunately, that hasn’t prevented the emergence of wildly speculative claims, often with little or no experimental evidence to back them up.

One common assertion is that seedlings benefit from being connected to mature trees via CMNs. However, across the 28 experiments that directly tackled that question, the answer varied depending on the trees’ species, and on when, where, and in what type of soil the seedling is planted. In other words, there is no consensus. Allowed to form CMNs with larger trees, some seedlings seem to perform better, others worse, and still others seem to behave no differently at all. Field experiments designed to allow roots of trees and seedlings to intermingle — as they would in natural forest conditions — cast still more doubt on the seedling hypothesis: In only 18 percent of those studies were the positive effects of CMNs strong enough to overcome the negative effects of root interactions. To say that seedlings generally grow or survive better when connected to CMNs is to make a generalization that simply isn’t supported by the published research.

Other widely reported claims — that trees use CMNs to signal danger, to recognize offspring, or to share nutrients with other trees — are based on similarly thin or misinterpreted evidence. How did such a weakly sourced narrative take such a strong grip on the public imagination?

We scientists shoulder some of the blame. We’re human. Years ago, when the early experiments were being done on forest fungi, some of us — the authors of this essay included — simply got caught up in the excitement of a new idea.

One of us (Jones) was involved in the first major field study on CMNs, published more than 25 years ago. That study found evidence of net carbon transfer between seedlings of two different species, and it posited that most of the carbon was transported through CMNs, while downplaying other possible explanations. This is what’s known as “confirmation bias,” and it is an easy trap to fall into. As hard as it is to admit, it was only due to our skepticism of the recent extraordinary claims about the wood-wide web that we looked back and saw the bias in our own work.

Over decades, these and other distortions have propagated in the academic literature on CMNs, steering the scientific discourse further and further away from reality, similar to a game of “telephone.” In our review, we found that the results of older, influential field studies of CMNs have been increasingly misrepresented by the newer papers that cite them. Among peer reviewed papers published in 2022, fewer than half the statements made about the original field studies could be considered accurate. A 2009 study that used genetic techniques to map the distribution of mycorrhizal fungi, for instance, is now frequently cited as evidence that trees transfer nutrients to one another through CMNs — even though that study did not actually investigate nutrient transfer. In addition, alternative hypotheses provided by the original authors were typically not mentioned in the newer studies.

As these biases have spilled over into the media, the narrative has caught fire. And no wonder: If scientists themselves could be seduced by potentially sensational findings, it is not surprising that the media could too.

Among peer reviewed papers published in 2022, fewer than half the statements made about the original field studies could be considered accurate.

Journalists told emotional, persuasive, and seductive stories about the wood-wide web, amplifying the speculations of a few scientists through powerful storytelling. Writers imbued trees with human qualities, portraying them as conscious actors using fungi to serve their needs. Fantasy moved to the foreground, facts to the back. In an odd kind of mutual reinforcement, the media blitz may have convinced experts in other subfields of ecology that the claims about CMNs were well-founded.

The episode underscores how important it is for journalists to seek out a broad range of expert opinions, and to challenge us scientists when our assertions aren’t clearly backed up by rigorous research. By directly asking scientists questions such as “What other phenomena could explain your results?” and “How many other studies support this hypothesis?” journalists may be able to better understand and convey some of the uncertainty around scientific conclusions. The best science writing can capture the hearts and minds of the public, but it must be true to the evidence and the scientific process. If not, the consequences can be far-reaching, affecting policy decisions that impact real people.

There are many captivating and scientifically well-grounded stories we can tell about fungi in forests — and we should. Mycorrhizal fungi underlie many of our favorite edible mushrooms, including truffles, chanterelles, and porcinis. And some herbs in the understories of forests, rather than photosynthesizing sugars like a normal plant, use CMNs to connect to trees and steal their sugars. Forests are fascinating places, marked by a rich diversity of interactions between plants, animals, and microbes. The stories are endless. We just have to tell them with care.

Melanie Jones is a professor in the Biology Department at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus. She and her students have been studying mycorrhizal fungal communities in forests, clearcuts, and wildfire sites in British Columbia for 35 years.

Jason Hoeksema is a professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Mississippi. His research addresses a diversity of questions regarding the ecological and evolutionary consequences of species interactions on populations, communities, and ecosystems.

Justine Karst is an associate professor in the Department of Renewable Resources at the University of Alberta. She has been studying the mycorrhizal ecology of forests for 20 years.

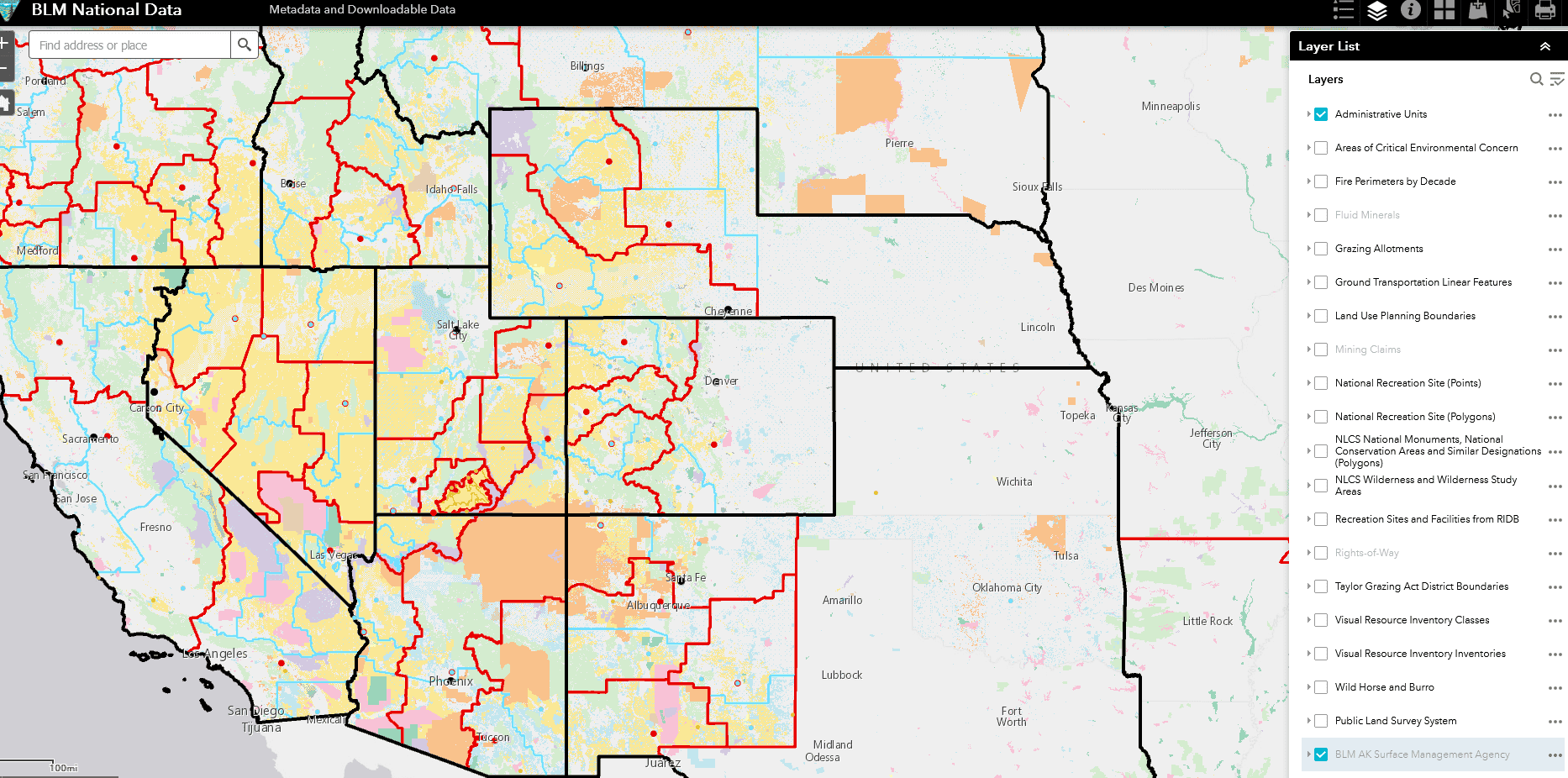

No Meetings for You- WY, UT ID OR- And Burr on the BLM Conservation Rule

Look at all the BLM land across the West. The meetings are in Nevada, New Mexico and Colorado, and yet Utah, Wyoming, Idaho and eastern Oregon also have large chunks of BLM. What do the States of NM CO and NV have in common that aren’t shared by WY UT and ID? Let me think…

Anyway, thanks, Greg Beardslee, for this link!

Burr: Bureau of Land Management has it wrong with new conservation rule

Landscape Health and Conservation Rule would allow conservation leases on potentially all of the 247 million acres of land managed by BLM.

Ben Burr is Executive Director of BlueRibbon Coalition

In the early days of his presidency, President Biden laid out his vision to comply with the 30 x 30 agenda, which is a marketing scheme developed by hardline environmental groups to justify locking up 30% of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. Those of us who understood he had no legislative mandate to propose such a vision wondered what administrative chicanery would be deployed as an extra-constitutional workaround to accomplish something the American people didn’t ask for.

Now we know. The plan is to sell off our public lands to the same environmental groups who schemed up the 30 x 30 agenda.

This will be accomplished by the Bureau of Land Management’s recently proposed Landscape Health and Conservation Rule. According to the BLM, secret statutory authority has been hiding in plain sight for 50 years in the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) that would allow them to create and sell conservation leases on potentially all of the 247 million acres of land managed by the BLM.

This rule is problematic and should be withdrawn. At the BlueRibbon Coalition we are working to unite public land users of all types to oppose this rule for the following reasons:

First, the Bureau of Land Management doesn’t have the authority to create this rule out of administrative thin air. FLPMA doesn’t contemplate a conservation lease scheme, and if Congress wanted the BLM to administer such a program, they would have expressly authorized it. This scheme would also likely raise revenue for the government, which again, is something BLM doesn’t have authority to do. Only Congress, can authorize a new program like this that raises revenue for the government.

Second, this rule won’t work. I have reviewed BLM project files where the agency and high-minded conservation organizations have entered into agreements to manage land towards conservation priorities. In these cases, all parties to the agreement flagrantly neglected to uphold the terms and conditions of the agreement. If the conservation leases don’t have any teeth for non-compliance, then they could cede management control of public lands to 3rd parties at the same time the public will have few if any tools to hold the 3rd parties accountable for non-compliance.

Third, this rule is unnecessary. The BLM is already required to comply with dozens of other laws and executive orders to prioritize conservation on public lands. Scores of environmental lawsuits that get filed every year ensure that the compliance with these laws is taken seriously. Despite the statutory requirement the BLM has to manage public lands for multiple use, conservation is prioritized above all other uses on a regular basis.

Fourth, this rule could easily lead to unintended intervention into public land management by foreign governments. If the government of Brazil wanted to further monopolize the American beef industry, it could funnel dark money to organizations that oppose public land grazing that could use the funds to acquire conservation leases on public grazing allotments to interfere with those grazing operations. If China wanted to kill an American lithium industry in its infancy, it could fund wildlife protection organizations to acquire conservation leases in areas rich with lithium.

As a leading national non-profit that works to protect recreation access to public land, at the BlueRibbon Coalition we are worried that this rule will be used to limit motorized recreation, dispersed camping, and all other forms of outdoor recreation on public lands. This rule will be a way for conservation organizations to create de facto wilderness, where they have failed to get Congress to make such restrictive designations. The $800 billion outdoor recreation industry thrives because of BLM’s careful efforts to balance conservation with other uses. By prioritizing conservation even more than it already is, we will undermine an industry that is fueling the livelihoods of many who live in the West.

We are grateful for the leadership of Representative John Curtis, who has introduced HR 3997. This legislation instructs the BLM to withdraw this rule. The rest of the Utah delegation has supported this legislation with Senators Lee and Romney supporting a Senate companion bill. We are encouraging everyone who supports public access to public land and a strong American economy to join Utah’s congressional delegation in telling the Bureau of Land Management to withdraw this rule by visiting sharetrails.org/withdraw-the-rule/.

Benjamin Burr is the Executive Director of the BlueRibbon Coalition – a national nonprofit that has been working since 1987 to protect public access to public land

Tuesday’s House Resources Committee Hearing on Various Wildfire and Other Bills

A kind TSW reader sent me a Marc Heller story from E&E News. Here’s a link to the hearing on last Tuesday, May 23, 2023.

Troy Heithecker is a Forest Service Deputy Chief who testified in a hearing Tuesday. I didn’t much like the headline “GOP call for total fire suppression” since the bill says, according to the article:

A bill from Rep. Tom McClintock (R-Calif.) — H.R. 934 — would require the agency to put out every reported fire within 24 hours in forests in drought conditions, at high risk of wildfire or when the National Interagency Fire Center has set the highest level for national preparedness.

That doesn’t seem total to me. Not that I support the bill either, FWIW. Hopefully if the fire had a high chance of getting away due to conditions, or there were few resources available, the FS would do that without legislation. Of course it’s hard to predict the future. I’d see this as signalling to “be more careful, especially in my District.”

I know why the FS says this.. but people want to hear “we’ll be more careful” not “because you experienced it, it’s really not a problem because look at the national percentages. Tell that to the New Mexicans about prescribed fire.

But Heithecker said the agency already puts out as many as 98 percent of the wildfires reported within 24 hours. He estimates that perhaps 1 percent are monitored or allowed to burn for resource benefit, such as allowing naturally occurring fire to thin forests that have evolved with it for centuries.

Anyway, enough about wildfire.. what about NEPA?

McClintock proposed another bill, H.R. 188, to extend the use of 10,000-acre categorical exclusions from the National Environmental Policy Act that have been in place in the Sierra Nevada since the Obama administration.

The Forest Service supports much of that proposal, Heithecker said, while looking to work on the details.

While categorical exclusions from NEPA often draw criticism from environmental groups, Heithecker defended them as “just another category of NEPA” that allows the Forest Service to move faster on projects that don’t pose a significant environmental risk.

As many as 85 percent of the NEPA-related decisions the Forest Service makes are done through categorical exclusions, he said, and many of the decisions involve tracts of land bigger than 10,000 acres.

“Having tools to help us do that work at scale faster is a benefit to us,” he said.

Even with the expedited reviews, Heithecker said, projects “have to comply with all of those environmental laws.”

I think it’s unclear that re-upping outfitter-guide special use permits, or permitting bike races, with a CE, should be in the same “85% of decisions” box as vegetation treatments. When people testify about fuel treatments, why not use the CE numbers for.. fuel treatments? I am still interested in the CEs currently available and how often they are used for fuel projects compared to EAs and EISs, and the relative amounts of acreage involved. Chelsea Pennick looked at that in Idaho, as I recall, when she studied collaboration but what do we know about the Sierra? Because, as we have seen, people on the Tahoe are successfully using EAs for 2K acre projects. Maybe CEs are not the answer, after all Lake Tahoe has its own CE. It would be interesting to talk to NEPA practitioners in the Sierra about this. Any of you out there, please email me.

If any folks have other observations on the hearing, please comment.

Public Meeting Tonight in Golden Colorado on BLM Proposed Public Lands Rule

Note from Sharon- this seems a little light on public meetings compared to national FS efforts like Roadless and Planning Rules. They are in three cities, Denver, Albuquerque and Reno (not Salt Lake?). Plus two virtual meetings.

Proposed Public Lands Rule

Rule would protect healthy public lands, promote habitat conservation and restoration and further thoughtful development

WASHINGTON — The Bureau of Land Management has updated its schedule for five public meetings that will provide forums across the country for the public to learn more about the proposed Public Lands Rule and have questions answered.

The proposed Public Lands Rule, which was announced in late March, would provide tools for the BLM to protect healthy public lands in the face of increasing drought, wildfire and climate impacts; conserve important wildlife habitat and intact landscapes; better use science and data in decision-making; plan for thoughtful development; and better recognize unique cultural and natural resources on public lands.

The BLM intends to host two virtual and three in-person meetings to provide detailed information about the proposal. Members of the public will have an opportunity to ask questions that facilitate a deeper understanding of the proposal. The dates and cities of the meetings are:

Virtual meeting on Monday, May 15, 2023, from 5-7 p.m. MT

Register at https://swca.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_S4-EBLxqRHa-yikYQQUNQw)

Denver, Colorado, on Thursday, May 25, 2023, from 5-7 p.m. MT

Denver West Marriott, 1717 Denver West Blvd, Golden, Colorado

Albuquerque, New Mexico on Tuesday, May 30, 2023, from 5-7 p.m. MT

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, 2401 12th Street NW, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Reno, Nevada on Thursday, June 1, 2023, from 5-7 p.m. PT

Reno-Sparks Convention Center, 4950 S Virginia Street, Reno, Nevada

Virtual meeting on Monday, June 5, 2023, from 9:30-11:30 a.m. MT

Register at https://swca.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_QwRH6XZeS6amUDI70FzriA

The proposal would help the BLM fulfill its mission, ensuring public lands and the resources they provide are available now and in the future. The proposed rule would build on the historic investments in public lands and waters, restoration and resilience, and clean energy deployment provided by President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act. It would not prevent new or continuing recreational or commercial uses of our public lands, such as grazing, energy development, camping, climbing, and more.

“Our public lands are remarkable places that provide clean water, homes for wildlife, food, energy, and lifetime memories,” said Bureau of Land Management Director Tracy Stone-Manning. “We want to hear from our permittees as well as the millions of visitors who hunt, fish and recreate on our public lands on how to keep them healthy and available for generations to come.”

In addition to these informational public meetings, the BLM wants to hear from the public on the proposed Public Lands Rule. To learn more about this proposed rule, or to provide comment, please visit the Conservation and Landscape Health rule on https://www.regulations.gov. The public comment period is open until June 20, 2023.

-BLM-

Fire Retardant Case/Legislation Update

I am trying to catch up and Nick Smith linked to this this morning; maybe someone else has a better status report?

Based on this article.. apparently the US is going to settle while being willing to “work with Congress on legislation”? I’m sure Andy knows more about the former but maybe can’t talk about it.

Inside EPA, which broke the news of the Forest Service’s decision to settle the citizen suit, is reporting that the head of the Forest Service now “is willing to work with Congress on legislation to allow the service to continue airborne sprays of firefighting chemicals” without the need for a multitude of Federal and State permits.

But apparently the Admin doesn’t support the existing House bill (I still hear, as previously reported, that it’s USDA and the FS are in one place and CEQ in another). It will be interesting to see what comes of this.

For those who want to know how my FOIAs of discussions between the Department and the White House (CEQ) on this topic are going.. well..so far USDA is winning the FOIA race with CEQ, but have nothing in my hands yet.

Why Are Some Federal Lands Users Assumed to be No-Goodniks and Others Given the Benefit of the Doubt?

For those interested in the etymology of “no-goodnik”, here’s a link.

I attended a Western Governors’ Association meeting a while back and Lesli Allison of the Western Landowners Alliance said something like “partnering with people can get us farther down the road than enemizing each other.” If this sounds a bit like Michael Webber on decarbonization. As I said in that post:

As in Webber’s essay in Mechanical Engineering, he talks about how this is an “all hands on deck” moment for climate, and we are “better rowing together in the same boat in the same direction.” We need everybody, but it’s hard to take leadership towards a future vision that does not include you.

This might remind you of the timber or grazing workers/industry (“Oil consumption is as much about demand as supply”), or the “vision that does not include you” might resonate with OHV or MB folks.

When do we work with people, and when do we try to get rid of them? Who is behind the decision to enemize or not? Why do we assume the best about wind developers changing practices to reduce bird mortality, but assume the worst about ranchers? It’s almost as if there are “our people and industries” whom we trust to try to do the right thing, and “their people and industries” who need to be heavily regulated because they are not, what? Moral? This seems like an underpinning of many of our discussions nowadays. It comes up in federal land most frequently, but is also found with regards to private land.

Federal lands grazing is not new to me. I remember when some of the ranchers from our tiny community of Lakeview, Oregon, were invited to Ronald Reagan’s first inauguration in 1981. I drove my FS rig over my share of cow patties, in fact when easing my way through a cattle drive I was called a “piss fir.” I still consider them sometimes annoying but legitimate. And who isn’t sometimes annoying?

Fast forward to a conference in 2010 at the University of Colorado Law School Center for Natural Resources on the 40th Anniversary of the Public Land Law Review Commissions’ Report, and our Regional Forester (Rick Cables) was speaking on forest planning with some help from me. Anyway, a fellow named Joe Feller spoke about grazing. He is now deceased, but you can check out his bio here. His attitude was different from anything I had ever seen or experienced.. snarky, as if ranchers were some lower life form (in fact, many speakers at the conference had an air of superiority coupled with some snarkitude). I know many environmental and natural resource law folks are readers of TSW and your contributions are greatly appreciated. I’m just saying that culturally the atmosphere was very different than those at conferences more focused on practices, say, what you might find at a land grant school. It was almost as if ranchers were some kind of inferior life form. Why they might be is a question. And none were actually there at the conference, as far as I could tell.

So through time, we’ve seen the Sierra Club’s “no commercial logging” (1997), the “Cattle free by 93” movement and President Biden’s questionably legal promise of shutting down oil and gas on federal lands. And today that continues via the MOG effort and perhaps the new BLM conservation leasing rule. As to the Sierra Club and Cattle Free, I wonder whether a more collaborative view around improving practices would have been more successful. After all, thirty or so years later, we still have commercial logging and grazing. For those groups, why does “stop it” win over “improve practices”? Could it be because these groups are full of lawyers, and the details of practices are not their forte? If all you have is a hammer.. These efforts also decrease the decision space of local communities..feature or bug?

I have puzzled about this for a long time. I’ve developed different hypotheses but only one seems to fit the facts. We have traditional potentially environmentally destructive commercial uses like timber harvesting, grazing, mining, and fluid mineral production. Then we have good potentially environmentally destructive commercial uses like ski areas, solar and wind farms and strategic minerals (but not uranium). I’m interested in your hypotheses, because as much as I don’t like it, this is the best one I have found that explains this pattern. The people whose environmental practices are assumed to be good donate have tended to donate to one political party, while the others have donated to the other one. Concern for the environment, which naturally draws people together, rather than becoming a concern to bring people on board and unite us, has become divided (by some entities) into good guys and bad guys. But we don’t have to accept those views. We can, and many TSW-ites do, assume the best about other users of federal lands and try to tolerate them, even when some of them can be annoying. Because who among us isn’t? While sometimes I say “stone-casting seems to have become the national pastime”, it doesn’t have to be.