This morning, the third panel of the science forum discussed the latest approaches to species diversity.

Kevin McKelvey of the Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station began by emphasizing monitoring of species, where quantification is essential. (slides pdf) In the overall framework of planning, then monitoring, then a new plan, there is a very different data standard for planning than for monitoring. In planning, things really can’t be quantified – you ask what will fit the mission statement. The plan is the broad aspirational thing, but monitoring is the reality. He used a business analogy, where planning is launching a new product line, and monitoring is looking at the quarterly profits.

of the Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station began by emphasizing monitoring of species, where quantification is essential. (slides pdf) In the overall framework of planning, then monitoring, then a new plan, there is a very different data standard for planning than for monitoring. In planning, things really can’t be quantified – you ask what will fit the mission statement. The plan is the broad aspirational thing, but monitoring is the reality. He used a business analogy, where planning is launching a new product line, and monitoring is looking at the quarterly profits.

If monitoring is so important, why haven’t we done more? McKelvey gave two reasons. First, science has not provided the appropriate tools and direction. Second, monitoring has been too expensive and difficult. But there are new monitoring methods that haven’t been around, even the last time we did a planning rule.

In the old way of monitoring, the gold standard was collecting population trend and size data over time. But you can’t get population data across large areas. You’d have to capture repeatedly a large portion of the population, which isn’t really posible across large geographic domains. Plus, even if you can get the data, it’s not really that useful. McKelvey used the example of the dynamics of voles, whose population data jump all over the place, so you can’t tell how they are doing. He also explained that indices aren’t useful, because we often don’t know the relationship between the index number and the population. One index often used is habitat. But he used an example where more grass doesn’t necessarily mean more elk: maybe the elk got shot out, or the grass was in the wrong place. Another index often used is surrogate species. But he used the examples of elephants which don’t indicate what other species are present.

Over the past three years a new idea has developed: looking at presence or absence. Presence/absence is not a surrogate for species abundance, but is a separate idea. It has to be both: presence and absence. You can estimate the likelihood of the false absence rate. Today, nearly an entire branch of statistics have developed on this idea. You can look at the area occupied over time, and whether or not the range is contracting. McKelvey said that species range is a better metric for population size for long term viability. It’s also important for monitoring range shifts due to climate change. Plus, the spatial part of the analysis is a nice hook to looking at management being done on the land. Presence/absence is easier to collect than abundance data.

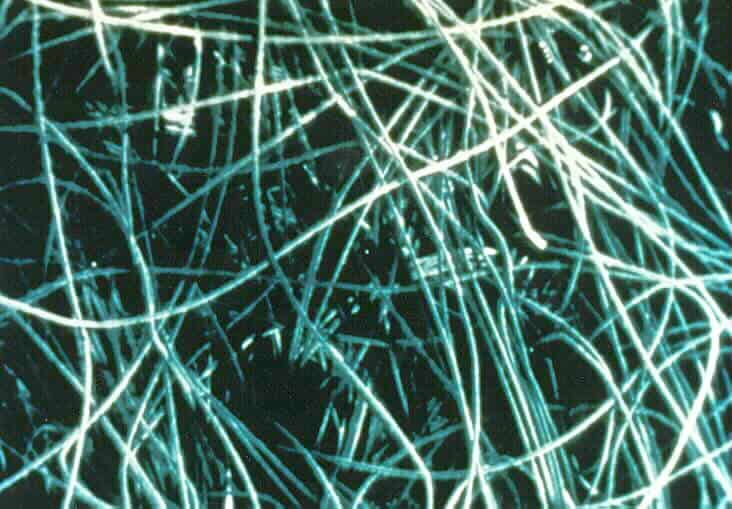

There is an exciting new suite of tools: forensic DNA stuff – collecting hairs, scats, etc. Just by sampling water, you can find the presence of fish DNA. This radically decreases the cost, and level of skill for person collecting the data. It’s not the skills of something like a breeding bird survey.

Presence/absence has some problems because it is insensitive to things like habitat fragmentation. It tells you the “wheres” of it all but not how the population is put together. So McKelvey urges a second monitoring method: looking at landscape genetics, which is really good at filling the gaps in knowledge. In most cases if you’re handling the data or detritus you have enough data to do genetic samples. Historically, lab costs have been a big deal. In 1990 it cost $10 for one base pair. Those costs were reduced to only $1 for up to 1 million pairs, and now it’s even 1/3 of that. This stuff will be cheap and fast. McKelvey gave an example of a study on wolverines, where they identified corridors based on empirical data.

Marilyn Stoll,  a biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service in Florida discussed the integration of science, policy, and stakeholder involvement in her recovery work in the Everglades. (slides pdf) She said that there are many legal authorities for an ecosystem approach, including the affirmative obligations of the section 7(a)(1) of the Endangered Species Act.

a biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service in Florida discussed the integration of science, policy, and stakeholder involvement in her recovery work in the Everglades. (slides pdf) She said that there are many legal authorities for an ecosystem approach, including the affirmative obligations of the section 7(a)(1) of the Endangered Species Act.

Stoll said that recovery plans contain important information that should be used in land management planning. For instance, the South Florida recovery plan covers 68 species, and it contains new science and recovery tasks. It addresses 23 natural ecosystems and lists restoration tasks. She explained the need to communicate with others in order to implement the actions. She mentioned that recovery plans are helpful when you look at the reasons the species were listed, and what were the threats.

Stoll described a conceptual model under ESA section 7(a)(2) where you look at how species status can decline from healthy populations, to concern species, candidate, proposed, threatened, endangered, and lastly in jeopardy. It might be helpful to think about where in the model the species currently is, and which way it’s headed. You look at the baseline, status of the species, effects of the proposed action and cumulative effects (state and private actions)– those are the components of the jeopardy analysis.

In the Everglades, she is looking at water quality, timing, and distribution. There is an engineered system they are trying to restore. They are developing an integrated science strategy, with adaptive management at different scales. More importantly, they are communicating the science for all different audiences at all different times. This varies from easy to read stuff like maps colored green or red, to more complex ecological models, focusing on hypothesis clusters. Stoll gave a few examples, including restoring the channelized basin around the Kissimmee River, and addressing the barrier created by a road and canal.

Gary Morishima,  a private consultant in Washington state, emphasized a holistic approach. (slides pdf) In explaining how we must look beyond borders, he quoted Chief Seattle: “All things are connected. Whatever befalls the earth, befalls the sons of the earth.” Morishima said that tribes have traditionally managed lands according to this tradition.

a private consultant in Washington state, emphasized a holistic approach. (slides pdf) In explaining how we must look beyond borders, he quoted Chief Seattle: “All things are connected. Whatever befalls the earth, befalls the sons of the earth.” Morishima said that tribes have traditionally managed lands according to this tradition.

Morishima said there is no firm definition of biodiversity. He said the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity has said that it’s the variety of life, but it’s valued by different people and cultures for different reasons which range from aesthetic to economic. Over history most species have become extinct. Nature is indifferent. Ecology and evolution are intertwined. The environment is inherent unstable, species adapt or they die. Human societies have evolved during the holicene period, a period of relative stability. Although some human influence is not bad, and sometimes species richness is improved due to human involvement, some have talked about a 6th great mass extinction era being cause by humans. We care because of our ethics and values. 2010 is the international year of biodiversity by the U.N. No international reports since 1992 have showed any improvements. 2011 will be the U.N. international year of forests.

Morishima said that our society’s emphasis on individualism, concept of property, and the drive to accumulate private capital lead us to becoming “pixelized” at the smallest possible unit. This leads to isolation, fragmentation, compartmentalism, and costs being transfered to others. This pixelized view of the world is hard to put back together again. He gave an example of King County, Washington, with a land ownership pattern that is highly pixelized: missing landscape components, disconnected properties, externalities, and divergence of management goals. The land ownership is not coincident with ecosystem function, and even the National Forest has been pixelized by management allocation schemes of allowed/restricted/prohibited. Nationwide, forests are disappearing, as landownership is becoming more fragmented into smaller parcels.

Morishima said that it’s time to step back and think things over, to determine the right goals, and whether the goals are effective to manage for a suite of benefits. We need to ask what society wants from our forests, both economic and ecological. Often, we can’t get there from here, and many of the things we want we can’t get, when we just look within administrative boundaries. The big question is how do we coordinate and integrate. He said that species goals can’t be done on Forest Service lands alone. We need a system view. Not all forest lands are equal, and we can’t expect everything for everyone, everwhere all the time.

Morishima gave some examples of “greenprinting” in King County, where ecological values are assigned to each parcel. Another concept is to use “anchor forests” on the landscape to support transportation, manufacturing, forest health, and ecosystem function.

He talked about the obstacles of communication and distrust. Distrust arises from perceptions of risk. He cited Ezrahi’s work on pragmatic rationalism, describing the relationship between politicians and scientific experts. If they both agree, there is an efficient means to the end. If they both disagree, you can have biostitution. There is a need to search for “serviceable truth” that does not sacrifice social interests for scientific certainty. There is no free lunch.

Morishima explained a new paradigm of panarchy (see Dave Iverson’s related post), resiliency, and consideration of social and ecological systems. Later, in a followup question, Morishima said that panarchy is based on the recognition that we can’t know, much less control everything in the system. So we need to develop systems adapted to change and disturbance – both socially and ecologically. He said that integration work has to be supported. What the public wants is not input – they want influence.

He quoted the Secretary of Agriculture’s all lands/all hands approach, to work collaboratively to effectuate cooperation. The Forest Service must change, overcome institutional barriers to collaboration, and a relectance to devolve decision making. We must support collaboration at the local level, stakeholder involvement, independent facilitation, and multidisciplinary communication. We need to replace our pixelized window on the world with a landscape view of social and economic processes and realities. Morishima concluded by saying that this new approach is not so new after all: it’s a reflection of native Americans for generations. All things are connected, part of the earth, part of this, for we are merely a strand in the world – we didn’t create the world.

Bill Zielinski  of the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station concluded the panel presentation with a discussion of the conceptual thinking of conservation planning. (slides pdf) He talked about the two common components, sometimes called “coarse filter” and “fine filter.” A coarse filter approach assumes a representation of ecological types and ecological process. A fine filter approach is a complement to look at specialized elements. Most scientists seem to agree that a combination is a decent compromise, as used by the Nature Conservancy, and the forest restoration approach described by Tom Sisk in the first day of the science forum. Zielinski said the coarse filter is cost effective and easy to implement (Schulte et. al. 2006), but it assumes you have information on vegetation composition and structure. It’s more than cover types and seral stages, which are not a predictor of populations. More commonly, the literature (for instance Noon et. al., 2009; Schlossberg and King, 2008; Flather, et. al, 1997) shows a wide distribution of population sizes within a vegetation type. The other shortcoming of a coarse filter approach is the rare local types. The fine filter approach assumes you are have indices, now the use of presence/absence monitoring.

of the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station concluded the panel presentation with a discussion of the conceptual thinking of conservation planning. (slides pdf) He talked about the two common components, sometimes called “coarse filter” and “fine filter.” A coarse filter approach assumes a representation of ecological types and ecological process. A fine filter approach is a complement to look at specialized elements. Most scientists seem to agree that a combination is a decent compromise, as used by the Nature Conservancy, and the forest restoration approach described by Tom Sisk in the first day of the science forum. Zielinski said the coarse filter is cost effective and easy to implement (Schulte et. al. 2006), but it assumes you have information on vegetation composition and structure. It’s more than cover types and seral stages, which are not a predictor of populations. More commonly, the literature (for instance Noon et. al., 2009; Schlossberg and King, 2008; Flather, et. al, 1997) shows a wide distribution of population sizes within a vegetation type. The other shortcoming of a coarse filter approach is the rare local types. The fine filter approach assumes you are have indices, now the use of presence/absence monitoring.

Zielinski said that we need to respect our ignorance – we don’t understand the complexity of nature sufficiently to develop a protocol for sustaining ecosystem. We often don’t know system dynamics, we don’t know what to protect, what to restore, or what to connect. But we can’t want to delay our actions until we understand the extent of diversity on public lands. He argued for a spatially extensive and economic method to collect info on species. Zielinski said that we can exploit existing platforms, like plots from the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA), and models like the Forest Vegetation Simulator (FVS). He used this existing information for small, high-density species to build a habitat model that can predict occurrence at all FIA plots. For instance, he was involved in a study that looked at 300 2.5-acre plots in Northern California for terrestrial mollusks. For larger animals with larger areas, he uses the same approach, but looks at an important habitat element like resting places. For instance, he was involved in a study that used FIA plots in four Southern Sierra Forests to predict resting habitat for fischers. He did it for two time steps of FIA series. He used FVS to predict conditions of stands and plots in the future. He linked FVS to FIA models that he built, so he could answer questions like the effects of thinning on fischers. He added that the approach can be expanded to multiple species with simple detection surveys. Later in the science panel session, Zielinski responded to a question from the audience about how sparse the FIA samples are, and how forests and districts will sometimes supplement the data.

Discussion

There were a number of follow-up questions for the panel.

Regarding the question of monitoring systems, Morishima said that they aren’t paying attention to the information that tribes have. They have a permanence of place: they will observe things, but won’t always express things in the terms that we use.

Responding to a question about conflict between ecosystem goals and species goals, Zielinski talked about ecosystem goals for thinning, but not all species benefit from those broader goals. Stoll said we need to manage for the at-risk species, because they are probably endangered because they are niche specialist.

Morishima said that the rule needs to avoid “rigidity traps”. We should focus on flexibility for species and social systems to adapt. Under panarchy and social/ecology integration, we need to let things self organize in order to provide for resilience.

Zielinski referred to the previous day’s examples in Connie Millar’s talk about pikas in high elevation microclimates. Forestry in the past has created homogenized environments. We need to take our guide from ecological proceses and look at heterogenous landscapes. Many species in a bind will have more local refugia – like the pika below the talus. Stoll added that climate change will also affect human populations and she encouraged landscape conservation cooperatives to look at human movement to climate change.

The panel also discussed how species should be selected for monitoring. McKelvey said there are number of criteria, some social, some functional. In region 1 they ranked species, emphasizing things like primary excavators or pollinators. Zielinski said that just when you try to believe there are key species, then the science shifts to the other species. The suite of species changes with science and society’s interest. McKelvey added that once you start monitoring – you’re in for a run. If 5 years into the game you want to do something else, you won’t produce anything coherent. Same with models – everything is changing: computer capacities, remote sensing capacities. But the monitoring is what you put in place 25 years ago. Regarding reduction in monitoring costs, McKelvey said you just go down the priority list until you run out of money. Zielinski takes a more practical approach, looking at “gravy data” or “incidental data.”

Somewhat surprising to the panel, a question about the 1982 rule viability provision didn’t come up until the end. Zielinski said that viability has had an interesting history. In its most formal definition it includes difficult data collection: you can’t compute the probability of persistence. Viability may be nuanced more these days, like maintenance of geographic range. Zielinski said that viability analysis is not his area of expertise but he thought the concept is evolving. McKelvey said the formal population viability analysis (PVA) process can’t be done. The determination of the probablility of surviving can’t be done. Think of Lewis and Clark predicting what the area they were exploring would look like in 200 years. McKelvey said that if you back up and look at the concepts, you think about what is well distributed and connected. If a population is doing that, it’s probably viable. If we monitor them, then we can contribute to viability. Morishima added that for many species, you can’t guarantee viability looking at forest service lands alone. The whole issue of diversity in the 1982 rule could set the Forest Service up for an impossible situation when you expand the concept to nonvertebrates. You could set up a “rigidity trap”. Stoll acknowledge that you still need PVAs for listed species.