I’ve gotten a little behind.

Settlement in Citizens for a Healthy Community v. U. S. Bureau of Land Management (D. Colo.)

On August 11, the BLM settled another case against its resource management plan decisions involving oil and gas leasing. Under the agreement, BLM will complete an amendment process for its Uncompahgre RMP, and prepare an EIS that will include alternatives that “reconsider the eligibility of lands open to oil and gas leasing, the designation and management of Areas of Critical Environmental Concern (“ACEC”), and management of lands with wilderness characteristics.” (Availability for leasing on national forest lands is not included, presumably because that decision is made in national forest plan rather than BLM RMPs.) With limited exceptions, new leases will not be issued prior to the amendment decision. The settlement also imposes a deadline on completion of range-wide Gunnison sage-grouse amendment from a previous settlement. (The news release includes a link to the agreement.)

On September 15, several logging contractors operating on the Malheur National Forest sued Iron Triangle, the recipient of a 2013 stewardship contract, for stifling competition. “Put simply,” the lawyers write, “Iron Triangle won the stewardship contract by assuring the Forest Service in its written proposal that it would administer the contract in a manner that diversified the local economy and promoted the public interest. Once the contract was secured, however, Iron Triangle did the exact opposite.”

Court decision in Donohoe v. U. S. Forest Service (D. Mont.)

On September 16, the district court denied plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction against the Custer-Gallatin National Forest pending appeal of the court’s March 29, 2022 decision to affirm the Forest Service decision to construct a trail and a bridge (the latter of which was already complete). The trail would adjoin plaintiffs’ property. The court found that harm to grizzly bears from increased human presence would be “speculative,” but had dismissed the ESA claim for failing to provide a Notice of Intent to sue. The court had earlier found no violation of NEPA scoping and connected action requirements, nor any violation of the forest plan. The original opinion is here.

Court decision in Washington Cattlemen’s Association v. USDC-CAOAK (9th Cir.)

On September 21, the 9th Circuit stayed the July 5th order of the Northern California district court that had vacated the Trump Administration rewrite of Endangered Species Act regulations. The circuit court held that the district court should have ruled on the validity of the regulations before it vacated them. The Biden Administration is revising these regulations, which affect the listing process and consultation, and had asked the court to NOT vacate the Trump rules while that is pending. The blog post above has a link to the 9th Circuit opinion. The district court decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. Haaland is linked to this article.

Court decision in Earth Island Institute v. Muldoon (E.D. Cal.)

On September 21, the district court held that fuel reduction projects in Yosemite National Park constituted “changes or amendments to” the current Fire Management Plan, which qualified them for a Park Service categorical exclusion, and denied a preliminary injunction. (See our prior discussion here.) The court noted that neither party had provided a definition of the quoted phrase, so it deferred to the Park Service, following a 7th Circuit case that had done something similar. (The Forest Service Planning Rule does clearly define forest plan amendments as something different from projects.) The court also allowed the Park Service to tier its categorical exclusion to a prior FMP EIS because the failure of the CEQ regulations to expressly allow tiering for CEs does not mean that it is prohibited. (The actual reason that the regulations do not mention tiering CEs is because environmental analysis is not relevant to determining if a CE applies, except to the extent it identifies “extraordinary circumstances.”) The court also found that the projects were properly “tiered to” existing plans (which I think must be comparable to “consistent with” Forest Service plans) – “at this stage of the case.” (The court used this or similar qualifiers multiple times throughout the opinion.)

One part of the NEPA issue in this case was whether a declaration by someone named Hanson had demonstrated a sufficient level of scientific controversy over the effects of fuel reduction. The court chose to not delve into it very deeply because of the “limited evidence before the court” at the injunction stage of the lawsuit.

Brief filed in Ohio Environmental Council v. U.S. Forest Service (S.D. Ohio)

On September 16, plaintiffs filed a reply brief in this case (so the complaint would have been filed months ago, but we have apparently not reported it) involving the Sunny Oaks Project on the Wayne National Forest. It would clearcut existing white oak forest, which plaintiffs assert “may also destroy the soil’s suitability for future oak ecosystem success.” The case includes NEPA claims, and “nullification” of a forest plan standard for loose bark tree retention for Indiana bats, allegedly illegal under NFMA, as well as violations of other forest plan guidelines. We’ve previously discussed white oak management here, and this article provides more background on the lawsuit. Plaintiff’s blog (above) has a link to the brief.

Court decision in Blue Mountains Biodiversity Project v. Jeffries (D. Oregon)

On September 26, the district court upheld a logging project in a developed recreation area on the Ochoco National Forest. The court held that the purpose and need for the project, to curb root rot in a developed recreation area, was consistent with the forest plan requirements to detect and treat diseases. (While this sounds like an NFMA consistency holding, it is actually a NEPA conclusion that a purpose and need for projects that is based on a forest plan is reasonable, suggesting that one that is not might not be.) The court also found that including an NFMA-required finding of a preliminary need to amend a forest plan as part of a project’s purpose and need does not violate NEPA (even though it may preclude project alternatives that don’t require an amendment, which it did not in this case, which is good because an amendment is a result of a project proposal, not a purpose). The court upheld the use of an EA instead of an EIS, and it adequately considered soil impacts. (The opinion alludes to previously granting plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment on something, but does not explain further.)

Court decision in Save the Bull Trout v. Williams (9th Cir.)

On September 28, the circuit court held that plaintiffs were barred from litigating the bull trout recovery plan in the Montana district court because some of the plaintiffs had previously made the same claims against the recovery plan in the Oregon district court (and lost). This blog post explains it further.

Court decision in Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (D. Oregon)

On September 30, the district court held that the FWS violated the ESA when they determined that old-growth logging by the BLM in the Poor Windy and Evans Creek timber sales on 15,848 acres of threatened northern spotted owl habitat would not jeopardize the species or adversely modify its critical habitat. In particular, the court found that the Service “was not faced with scientific uncertainty, but unanimity concerning the negative impact of reduced [nesting, roosting, and foraging] habitat and the barred owls’ threat to the spotted owl based on the barred owls’ ability to out-compete for food and shelter,” so its assumption that other areas would continue to support spotted owls was arbitrary. The court added that mitigation measures addressing barred owls are not “reasonably certain to occur.” The FWS determination of no “incidental take” was also arbitrary. The judge also found that the Bureau and the Service illegally failed to reinitiate consultation on the effects of the East Evans Creek and Milepost 97 wildfires that actively burned the timber sale area as the Service concluded its evaluation. Along the way, the court determined that a prior challenge to an RMP does not preclude raising the same issue for a project (so it does not create a similar situation to the bull trout case above). The court denied two other ESA claims.

New lawsuit: Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project v. Haaland (D. Ariz.)

On October 3, five conservation non-profits filed suit in Arizona against the July 1 revised Section 10(j) rule governing management of Mexican wolves in New Mexico as a “nonessential” experimental population, and preventing their further dispersal in the southwest. The news release includes a link to the complaint.

On October 11, a lawsuit was filed in the Montana federal district court against the Forest Service by Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics for violating the Clean Water Act by the continued use of chemical flame retardant from aircraft.

A notice of a final rule to delist the snail darter from protection under the Endangered Species Act was published October 5, at the request of the Center for Biological Diversity, among others. The fish is known for stopping the construction of the Tellico Dam on the Tennessee River in the first test of ESA in the Supreme Court. While the dam was later authorized by Congress, other measures resulting from ESA are credited with the species’ recovery. More in this article.

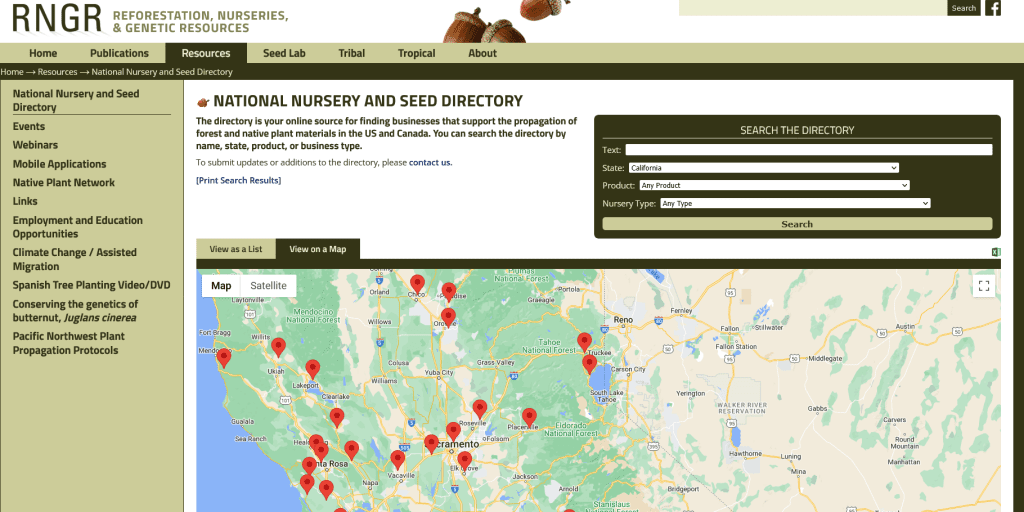

The seedling program allows farmers, ranchers, other landowners and land managers to obtain trees at a nominal cost to help achieve conservation goals, including:

The seedling program allows farmers, ranchers, other landowners and land managers to obtain trees at a nominal cost to help achieve conservation goals, including: