I’ve been digging through my old Kodachrome slides, and I found this view of the Tuolumne River and Poopenaut Valley, within Yosemite National Park. This area burned in the Rim Fire, and it is representative of what lies below, in the Stanislaus National Forest. Of course, little of this would even be worth salvaging, even it is wasn’t in the National Park. You might notice the abundance of digger pines, even on the north-facing slopes. This is the beginning of an impressive canyon, and it becomes a Wild and Scenic River, when you reach the Park boundary. Of course, very little fuels work could have been done, within this awesome canyon. However, fuelbreaks could have been installed all along the edge of this canyon, knowing that there would eventually be an ignition, within the canyon. Lightning fires happen all the time in this portion of the Sierra Nevada. I really want to get in here and re-visit these spots, for some repeat photography.

wildfire

Largest “Dealbreaker” Ever?!?

This may shock some readers but, I am actually against HR 3188. I don’t support any logging in Yosemite National Park, or in the Emigrant Wilderness, other than hazard tree projects. What is also pretty amazing is that others in the House have signed on to this bill. It seems like political “suicide” to go on record, being in favor of this bill. However, I am in favor of exempting regular Forest Service lands, within the Rim Fire, from legal actions, as long as they display “due diligence” in addressing endangered species, and other environmental issues. Did McClintock not think that expedited Yosemite National Park logging would be, maybe, the largest “dealbreaker” in history?

Here is McClintock’s presentation:

HR 3188 – Timber Fire Salvage

October 3, 2013Mr. Chairman:I want to thank you for holding this hearing today and for the speedy consideration of HR 3188.It is estimated that up to one billion board feet of fire-killed timber can still be salvaged out of the forests devastated by the Yosemite Rim fire, but it requires immediate action. As time passes, the value of this dead timber declines until after a year or so it becomes unsalvageable.The Reading Fire in Lassen occurred more than one year ago. The Forest Service has just gotten around to selling salvage rights last month. In the year the Forest Service has taken to plow through endless environmental reviews, all of the trees under 18” in diameter – which is most of them – have become worthless.After a year’s delay for bureaucratic paperwork, extreme environmental groups will often file suits to run out the clock, and the 9th Circuit Court of appeals has become infamous for blocking salvage operations.We have no time to waste in the aftermath of the Yosemite Rim Fire, which destroyed more than 400 square miles of forest in the Stanislaus National Forest and the Yosemite National Park — the largest fire ever recorded in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.The situation is particularly urgent because of the early infestation of bark beetles which have already been observed attacking the dead trees. As they do so, the commercial value of those trees drops by half.Four hundred miles of roads are now in jeopardy. If nearby trees are not removed before winter, we can expect dead trees to begin toppling, risking lives and closing access. Although the Forest Service has expedited a salvage sale on road and utility rights of way as part of the immediate emergency measures, current law otherwise only allows a categorical exemption for just 250 acres – enough to protect just 10 miles of road.By the time the normal environmental review of salvage operations has been completed in a year, what was once forest land will have already begun converting to brush land, and by the following year reforestation will become infinitely more difficult and expensive – especially if access has been lost due to impassibility of roads. By that time, only trees over 30 inches in diameter will be salvageable.Within two years, five to eight feet of brush will have built up and the big trees will begin toppling on this tinder. You could not possibly build a more perfect fire than that.If we want to stop the conversion of this forestland to brush land, the dead timber has to come out. If we take it out now, we can actually sell salvage rights, providing revenue to the treasury that could then be used for reforestation. If we go through the normal environmental reviews and litigation, the timber will be worthless, and instead of someone paying US to remove the timber, WE will have to pay someone else to do so. The price tag for that will be breathtaking. We will then have to remove the accumulated brush to give seedlings a chance to survive – another very expensive proposition.This legislation simply waives the environmental review process for salvage operations on land where the environment has already been incinerated, and allows the government to be paid for the removal of already dead timber, rather than having the government pay someone else.There is a radical body of opinion that says, just leave it alone and the forest will grow back.Indeed, it will, but not in our lifetimes. Nature gives brush first claim to the land – and it will be decades before the forest is able to fight its way back to reclaim that land.This measure has bi-partisan precedent. It is the same approach as offered by Democratic Senator Tom Daschle a few years ago to allow salvage of beetle-killed timber in the Black Hills National Forest.Finally, salvaging this timber would also throw an economic lifeline to communities already devastated by this fire as local mills can be brought to full employment for the first time in many years.Time is not our friend. We can act now and restore the forest, or we can dawdle until restoration will become cost prohibitive.

Why We Need to Salvage and Replant the Rim Fire

Greg asked why we should bother with salvage logging on the Rim Fire, and I tried to explain how bear clover would dominate landscapes. He also seemed confused about modern salvage projects, here in California. Everything, here in California, is fuels-driven, as wildfires happen up to 13 times per century, in some places in the Sierra Nevada.

This picture shows how dense the bear clover can be, blocking some of the germination and growth of conifer species. Additionally, bear clover is extremely flammable and oily, leading to re-burns. This project also included removing unmerchantable fuels, including leaving branches attached. Yes, it was truly a “fuels reduction project”. You might also notice how many trees died, from bark beetles, after this salvage sale was completed. Certainly, blackbacked woodpeckers can live here, despite the salvage logging. Hanson and the Ninth Circuit Court stopped other salvage sales in this project, in favor of the BBW.

When you combine this bear clover with a lack of fire salvage and chaparral brush, you end up with everything you need for a catastrophic, soils-damaging re-burn and enhanced erosion, which will impact long term recovery and the re-establishment of large tree forests. Actually, there has already been a re-burn within this project since salvage operations in 2006. Salvage logging greatly reduced that fire’s intensity, as it slicked-off the bear clover, but stayed on the ground. Certainly, if the area hadn’t been salvaged, those large amounts of fuels would have led to a much different outcome.

Now, if we apply these lessons to the Rim Fire, we can see how a lack of salvage in some areas within the Rim Fire will lead to enhanced future fires, and more soils damages and brushfields. When the Granite Fire was salvaged in the early 70’s, large areas were left “to recover on their own”, in favor of wildlife and other supposed “values”. When I worked on plantation thinning units there, those areas were 30 year old brushfields, with manzanita and ceanothus up to eight feet high. Those brushfields burned at moderate intensity, according to the burn severity map. Certainly, there were remnant logs left covered by those brushfields, leading to the higher burn severity. It was the exact same situation in my Yosemite Meadow Fire example, which as you could see by the pictures, did massive damage to the landscape, greatly affecting long term recovery. Here is the link to a view of one of those Rim Fire brushfields, surrounded by thinned plantations.

https://maps.google.com/maps?hl=en&ll=37.999904,-119.948199&spn=0.003792,0.008256&t=h&z=18

I’ve been waiting to get into this area but, I expect the fire area will remain closed until next year. The plantations were thinned and I hear that some of them did have some survival, despite drought conditions and high winds, during the wildfire. In this part of California, fuels are the critical factor in wildfire severity. Indians knew this, after thousands of years of experience. They knew how to “grow” old growth forests, dedicating substantial amounts of time and energy to “manage” their fuels for their own survival, safety and prosperity. Their preferred forest included old growth pines, large oak trees, very little other understory trees, and thick bear clover. Since wildfires in our modern world are a given, burning about every 20 to 40 years, we cannot be “preserving” fuels for the next inevitable wildfire.

We need to be able to burn these forests, without causing the overstory pines to die from cambium kill, or bark beetles. That simply cannot be done when unsalvaged fuels choke the landscape. We MUST intervene in the Rim Fire, to reduce the fuels for the next inevitable wildfire that WILL come, whether it is “natural”, or human-caused. “Protected” old growth endangered species habitats may now become “protected” fuels-choked brushfields, ready for the next catastrophic wildfire, without some “snag thinning”. We cannot just let “whatever happens”, happen, and the Rim Fire is a perfect example of “whatever happens”. Shouldn’t we be planning and acting to reduce those impacts, including the extreme costs of putting the Rim Fire out, and other significant human costs? Re-burns are a reality we cannot ignore, and doing nothing is unacceptable. Yes, much of the fire doesn’t have worthwhile salvage volumes, and that is OK but, there are less controversial salvage efforts we can and should be accomplishing.

Here is an example of salvage and bear clover, six months after logging with ground-based equipment. This looks like it will survive future wildfires. You can barely even see the stumps, today! The bear clover has covered them.

The Future of the Rim Fire?

These are 2011 views of the A-Rock/Meadow Fire re-burn, within Yosemite National Park, after 4 years of “recovery”. The actual “recovery” time is now at 24 years, since the original A-Rock Fire raged through majestic old growth. You can barely make out the road into Yosemite Valley. You might also notice a lack of any conifer trees growing back.

Even fire-adapted oak trees are doing very poorly, and the large snags from the previous stand, before the A-Rock Fire in 1989, are completely gone. Remember, no salvage logging happened away from roadside hazard trees.

This is how the Sierra Nevada “recovers” from catastrophic wildfires. It can take hundreds of years to re-grow a forest, without help from humans. Indeed, Yosemite is a living laboratory, and it is clearly showing us some “lessons learned”. It is also clear that any Yellowstone recovery parallel to Sierra Nevada wildfires is not supported by actual results.

Aerial view of the 1987 Complex Fire Salvage

I took this shot while flying with a Forest Service buddy in 1989.

I am pretty sure that this is Forest Service land, near the Groveland Ranger District office. When I worked there in 1990, the Timber Management Officer was still angry at the less-than-aggressive post-fire salvage efforts that allowed so many “brain dead” trees to die and add to the fuel loading. I’m sure that all those dead trees had some green needles on them as salvage logging was proceeding. As you can clearly see in the photo, there are PLENTY of snags left in this HUGE wildfire zone. This isn’t even where the fire burned hot. The subsequent bark beetle bloom spread northward, chewing up forests more than 100 miles away. On the Eldorado, our Ranger District harvested 300 million board feet, between 1989 and 1992, of dead and dying timber from the severe bark beetle infestation. We were lucky, able to slide our EIS into place before the litigators could gather their case together. The Tahoe National Forest was too slow, and lost 2 years worth of salvage logging opportunities, turning merchantable dead trees into future wildfire fuels.

The Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit was also hard hit, and slow to react. Here is a 1990 view of the north end of the Lake Tahoe Basin. My first two summers in the Forest Service were spent at the top of that mountain as the Martis Peak fire lookout. Of course, there are a LOT more dying trees up there than just the brown trees. So many of those trees became unmerchantable before they could be salvaged, as the public and eco-groups hoped that “nature” would take care of the problem. Since fire suppression in the Tahoe Basin is ensured, most of those dead trees are now horizontal, and perfectly preserved as fuels for the next big, destructive, erosion-causing, lake-polluting disaster.

Plantation Thinning Success on the Rim Fire

Derek tipped me off about the new BAER fire severity maps, yesterday, and I was happy to see that the efforts to thin plantations has resulted in lower fire intensities. Here is the link to both high and low resolution maps. It is not surprising that fire intensities outside of this thinning project I worked on were much higher, and I doubt that there was much survival in the unthinned plantations. Those plantations were the within the 1971 Granite Fire, and is yet another example of forest re-burn. This part of the fire has terrain that is relatively gentle, compared to the rest of the burned areas. To me, it is pretty clear that fuels modifications reduced fire intensities.

This photo below shows a boundary between burn intensities. The area east of road 2N89 was thinned and burned much cooler than the untreated areas to the west. The areas in between the plantations had moderate to high burn intensities, due to the thick manzanita and whitethorn. Those areas were left to “recover on their own”. The SPI lands did not fare as well, as they didn’t thin their plantations.

The highest burn intensities occurred in the old growth, near the Clavey River. Activists have long-cherished the areas around this river, and I am assuming that these were protected as spotted owl/goshawk PACs. As you can see, this area has very thick old growth, and it shows on the map as high intensity. This same scenario is one that Wildlife Biologists have been worrying about for many years, now. These wildlife areas have huge fuel-loading issues and choked understories. Prescribed fires cannot be safely accomplished in such areas, without some sort of fuels modifications. Last year, I worked in one unit (within an owl PAC) on the Eldorado where we were cutting trees between 10″ and 15″ dbh, so that it could be safely burned, within prescription.

Nearly all of the Groveland Ranger District’s old growth is now gone, due to wildfires in the last 50 years. What could we have done differently, in the last 20 years?

Rim Fire Op-Ed by Dr. Thomas Bonnicksen

This is where the Rim Fire “ran out of fuel”, in Yosemite National Park. Kibbie Lake is near the northeast flank of the fire, where there will be no firelines. Ironically, I was planning a hike to this area, a few weeks ago. (I shot this picture while flying with a forestry buddy, back in 1990. )

“Fire monsters can only devour landscapes if we feed them fuel. More than a century ago, we began protecting forests from fire. We did not know that lightning and Indian fires kept forests open and immune from monster fires. More recently, we adopted an anti-management philosophy that almost completely bans logging and thinning on public lands, even when it is designed to restore historic forests and prevent monster fires. Now, fallen trees and branches clutter the ground and young trees and brush grow so thick that it is difficult to walk through many forests. It is not surprising that the gentle fires of the past have become the fire monsters of the present.

Even so, we keep feeding fuel to the fire monster while blaming global warming, high winds, drought or any other excuse we can think of that keeps us from taking responsibility for the death and destruction these monsters create. We know the climate is warming just as it has done many times for millions of years. We also know that fires burn hotter when the temperature is high, fuel is dry and winds blow strong. Even so, these conditions only contribute to fire intensity. It is a scientific fact that a fire can’t burn without fuel. The more fuel the bigger the fire, regardless of drought or wind.”………. Dr. Thomas Bonnicksen

This article Here is in the local paper, here in Calaveras County, just an hour away from the Rim Fire.

www.facebook.com/LarryHarrellFotoware

Wildfires on the Groveland Ranger District

For over 40 years, I have watched the Yosemite area suffer large wildfires, losing most of its historic old growth. In 1971, I went to the Cherry Lake area, on a junior high field trip, to see forestry in action, on the old Granite Fire. In 1990, I helped lay out salvage cutting units in the A-Rock Fire. There is no doubt that California Indians meticulously managed their domains, including Yosemite Valley. Their ideal landscapes were composed of large, fire-resistant pines, canopies of California Black Oaks and a thick carpet of flammable bear clover. Their skills and knowledge resulted in the majestic pine forests that used to populate the area of the Groveland Ranger District, of the Stanislaus National Forest. This roughly-mapped view shows how large modern fires have decimated the area. Notice that the Granite Fire has been completely re-burned. Whether they are lightning strikes or human-caused wildfires, they are not like the pre-settlement fires ignited by the Indian wise men.

Historically, this area had awesome old growth forests that survived the extremes in terrain and climate. Below is a view of a part of the Rim Fire that I worked on in 2000. I personally flagged most of these units, enduring thick manzanita and whitethorn. In browsing around, I could see that the project was just finished, when Google collected their images. Landing piles have been burned and the large plantation thinnings were completed. You can see the brushy areas that were left “to recover on their own”, as concessions to wildlife. Fire crews appear to have initiated burnout operations along the road on the right side of the picture. You can also see a patch of private ground. There also appears to be some unthinned plantation on Forest Service land there, as well. There should be some great opportunities to compare treatments.

It is clear that we need to learn how to grow “all-aged” forests, which are also as fire resistant as they can be. The Tuolumne River canyon will continue to do as it always has. It will burn, despite what humans do. However, I believe we can act to contain fires to the canyon, for the most part.

www.facebook.com/LarryHarrellFotoware

Yosemite Wildfire Study

While browsing for historical fire maps, I ran across this interesting study of Yosemite wildfire issues. I scanned some of the study and felt it would be useful information.

I didn’t know that there are fewer individual and less severe wildfires in the early season, due to snowpack’s effect on thunderstorm development. The Forest Service land, where I took this 1990 picture of the A-Rock Fire, has burned 13 times in the last 100 years. Why did this particular wildfire kill so much old growth, when previous uncontrolled fires did not?

You can also see the fire’s “twin”, across the canyon. It also has suffered a re-burn, although it was the Park Service who let a fire get out of hand, on that incident too. The A-Rock re-burned when a prescribed fire was lit, and lost, within an hour of ignition. The Meadow Fire burned for weeks, costing $17 million, closing the Park during the height of tourist season. The Forest Service portion of the A-Rock Fire hasn’t re-burned, yet.

Air Tanker Video

I’m away from home now but, I just had to post this VERY interesting video of a military plane making a retardant drop on the Rim Fire. I think the radio conversation is with the lead plane. What an exciting job!!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_eGiGG1B-Q

There are also several other videos of this plane on You Tube.

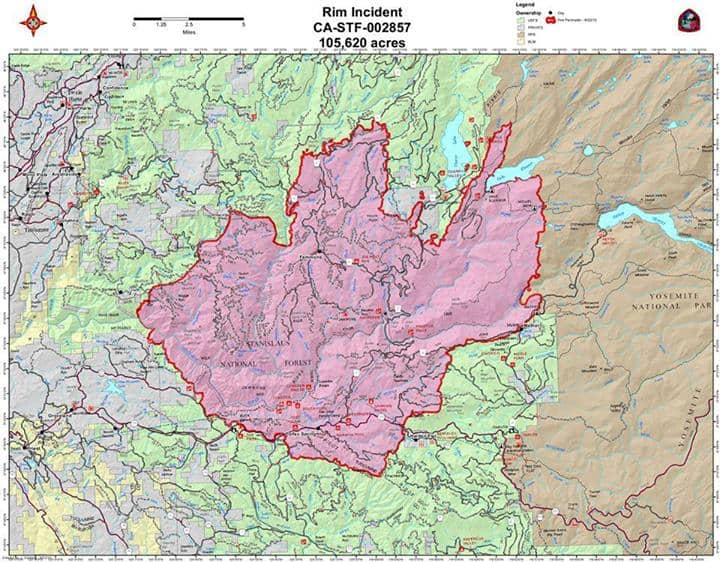

On a side note, I was still able to see the column over 100 miles away, from the city of Pleasanton, on Interstate 680. The smoke at my house this morning was so thick there was only 1/4 mile visibility, and the fire is about 40 miles away. The old burn perimeters haven’t even slowed down the fire, re-burning in at least 4 older burns. It’s looking REAL bad, with just 2% containment of a 105,000 acre fire.