Thanks to Chelsea McIver for providing this (investment study) about how the “benefit to local communities” consideration in the 2012 Appropriations Committee is working in practice.

Below are the conclusions..

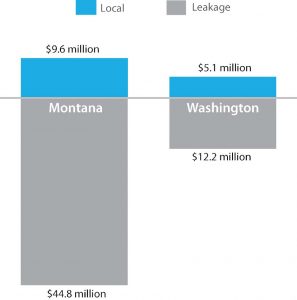

As these two case studies demonstrate, well over half of the value of federal investments in forest restoration and maintenance activities are being lost due to leakage out of local forest communities. Along with those dollars is the lost potential for that money to circulate and “multiply” in the local economy. So what can rural forest communities do to better leverage federal investments in forest management and restoration on public lands?

New programs and authorities are in place providing an opportunity for land management agencies and communities to work together to increase the utilization of local businesses. The Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP), established in 2009 has made job creation in local communities an explicit objective. Through 10 years of dedicated investments in restoration combined with active monitoring, the program hopes to increase the economic benefits of restoration activities accruing to local communities. Nonetheless, research by McIver (2013; 2016) and others (Moseley and Toth, 2004; Charnley et al., 2008) has shown that legislative intent alone is not enough to change the procurement contracting trends on the ground. As stated previously, government agencies need specific authorities that allow greater consideration of local contractors when awarding procurement contracts.

In 2012, Congress implemented such an authority. The fiscal year 2012 Consolidated Appropriations Act included language providing the Secretaries of Agriculture and Interior authority to consider the benefit to local communities in the awarding of contracts for forest hazardous fuels reduction and other forest and watershed restoration activities. The authority has been extended through FY17. Finally, as Abrams et al. (2015) and Pensky (1993) point out, the engagement of non-federal entities, such as community-based organizations or other non-profits, are critical for implementing import substitution programs due to their in-depth knowledge of a place, experience securing financial resources, and their ability to leverage networks to support their efforts. Careful analysis of federal contracting trends combined with local knowledge can create the foundation for a public-private effort to leveraging federal investments in forest maintenance and restoration to create wealth and build capacity in rural forest communities.

The thing I don’t get is that “Technical Work”accounted for 37% of the Forest Service’s investment in restoration in Montana, yet the FS is STACKED with soils scientists, hydrologists, engineers, fisheries biologist, wildlife biologists, survey teams, GIS support, etc. The list goes on. So why send a 3rd (!!!) of this money when you have that capacity in house!?! Mind boggling. So much more of that could be spent on “Labor Intensive” contracts and get more boots on the ground (not to mention anything about fire crews sitting around from May-June).

Smokey,

Your point is well taken, although I am sure you are also aware that Forest Service staffing levels are not what they used to be–and that includes the “ologists”. Much of the ‘technical’ type work is architecture and engineering services. Another good chunk is weed spraying and contracted out NEPA work.

I will also point out that not all jobs are created equal. Architecture and engineering jobs likely pay quite well which is not the case with most labor-intensive work. On the flip side, those labor-intensive jobs do not require as much education so have lower barriers to entry.

Any time we talk about jobs I believe it’s important to be clear about our values and objectives–are we interested in any new jobs? family-wage jobs? jobs for young people with less education/experience? Federal jobs?

Then why have both a forest and zone engineer if you contract engineering projects? Why have a NEPA planner and ID teams that consist of 20 plus people then contract a NEPA project?

I don’t buy your assumption that staffing levels are down (sure, compared to the 1970’s) so this work needs to get contracted. MT DNRC has a shoe string staff, manages 5.2 million acres and does most all it’s “technical” work in-house. There is a void in leadership…that is the real answer. I’m not even talking about jobs…

Smokey,

This graphic from the Forest Service documents the change in FS staffing levels between 1998 and 2015: https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/FS-staffing-1998-2015-.pdf. The number of NFS employees dropped from over 17,500 down to roughly 10,000 during this period.

A more detailed account of these changes in the PNW during the time of the Northwest Forest Plan can be found in an article by Charnley et al:

However, what I think I hear you saying is that you feel the agency is not using their resources efficiently. That is a more difficult thing to measure and I wish I had data for you on that!

Here’s the perspective from my time in service 1979-2012. Would like to hear other perspectives and from current employees. At one point, regions were staffed up for timber and road projects. But timber and roads fell by the wayside. Through some kind combo of attrition and the ideas that contracting is more flexible and effective, the tendency is to reduce from “doing work” to “administering contracts”.

A few years before I retired there was some effort toward “rightsizing”-can’t remember the name of it. The engineers took it seriously and had a plan to do better coordination and do the work more effectively (yay, engineers!). Minerals combined some staffing across regions and that worked for us-got more warm bodies to call on. Other groups were.. er…not as proactive.

I guess my point is that forests and regions started in different places, and went through different reductions for different reasons- not necessarily lined up with the staffs and budgets of today. People from time to time have noticed this and attempted to fix it, more or less (mostly less) successfully.

And yes, you can have a NEPA team and still need to contract out NEPA depending on the workload fluctuations.

Would like to hear other FS perspectives….

Yes, maybe like hiring someone to pull the ditch lines so we don’t lose our roads.

All good ideas but as far as I can see nothing is happening. Maybe two or three large thinning sales and the rest is all about meetings. Or maybe a service contract to one contractor. Basically they can’t care about the local communities, with all the laws and regulations, plus federal personnel are always moving around, at a meeting or on some kind of assignment. What local community? The non profits whose job it is to see that no timber is harvested and as much “wilderness” is created as possible?

Bob,

You would be surprised how many contracts the agency lets each year. For work in Flathead County alone, the Forest Service spends over $1 million per year on forest management and restoration through 75-100 individual contracts. I don’t see this as insignificant.

And as I mention in the report, the Forest Service does have tools allowing them to give preference to a local contractor, all else being equal (assuming the local contractor is equally qualified). Stewardship contracting is one tool that now has permanent authorization. The other is a newer authority that can be used on any service contract–it was established in 2012 and expires this fiscal year unless congress extends it. Getting the agency to use these tools can be a challenge, but they do exist.