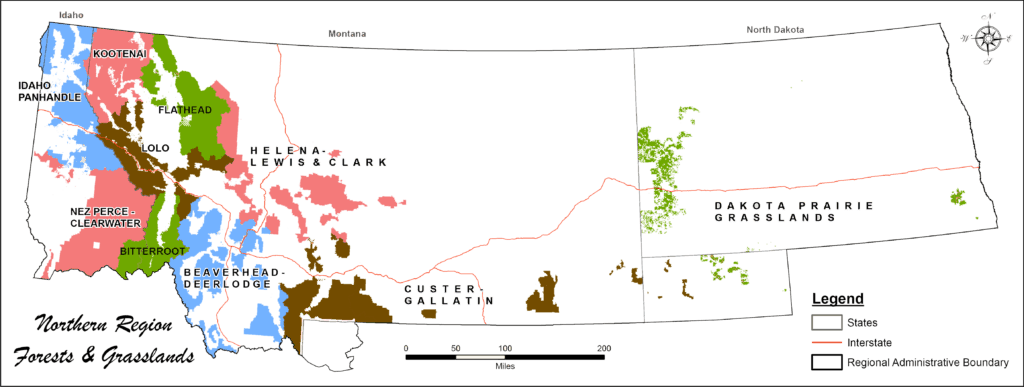

Wilderness designation has always been controversial in Montana. No new wilderness areas have been established by Congress since I believe 1977, and unlike most states there has never been statewide wilderness legislation. The Blackfoot-Clearwater proposal to designate 90,000 acres on the Lolo National Forest was locally developed and has been pending in Congress for several years. Its development included addressing issues related to motorized and mechanized recreation that we have been discussing here, and designates areas for both. This article provides some background, and includes a link to the written statement from the Forest Service regarding the proposed legislation.

The statement relates to forest planning in a couple of ways. First, the Forest Service uses the Lolo National Forest forest plan as the foundation for its position on the legislation.

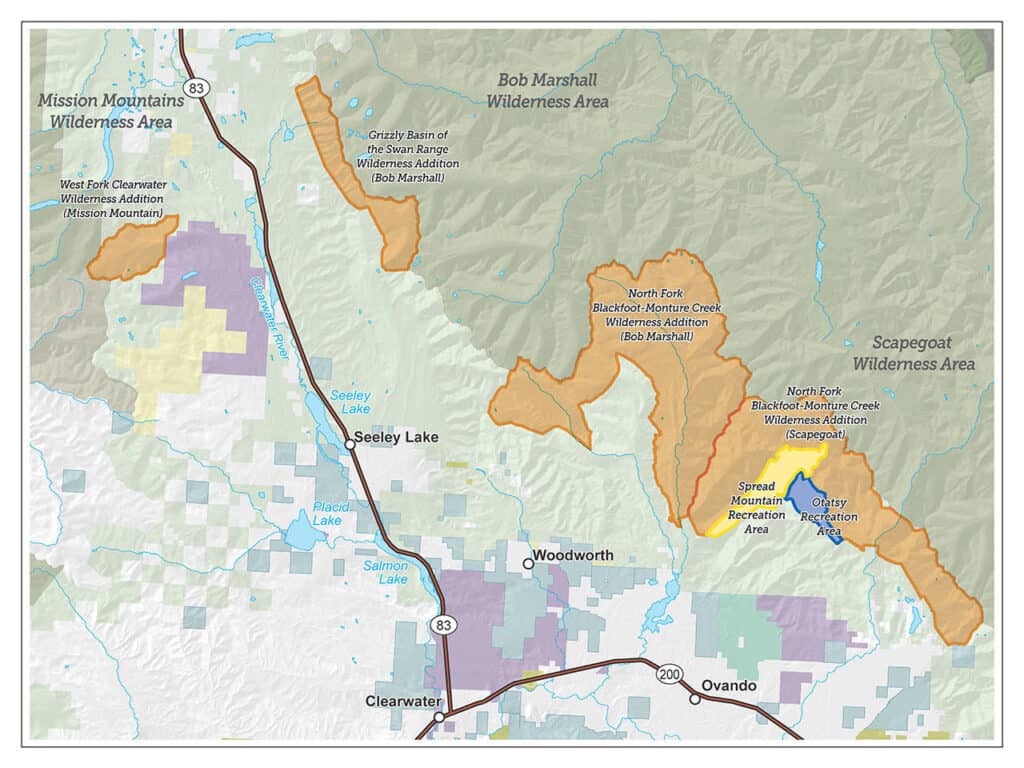

We also have concerns about implementing section 202, which establishes the Spread Mountain Recreation Area for the apparent purpose of enhancing mountain biking opportunities. The Lolo’s current land and resource management plan identifies this area as recommended wilderness. This area is characterized generally by steep topography, sensitive soils, and contains sensitive fish and wildlife habitat. Trail 166 is the main access into this area. This trail is not maintained, not passable by riders on horseback, and becomes difficult to locate after the first mile. While we acknowledge the interest in expanding opportunities for mountain biking on the Lolo, we are concerned that the site designated for the Spread Mountain Recreation Area is not well-suited for this use, and that this designation could create conflicts with wildlife and other recreation uses.

Two of the three wilderness designations in Title III are consistent with the recommendations made in the existing Lolo National Forest land and resource management plan. The third designation (West Fork Clearwater) was not recommended in the management plan to be Wilderness, it was allocated to be managed to optimize recovery of the Grizzly Bear.

One might argue that the 1986 forest plan is outdated, and recent local efforts should be given greater consideration. However, those efforts have not been through any formal public process, so I commend the Forest Service for using its forest plan. I’m not sure whether NFMA’s consistency requirement applies to taking positions on legislation, but it is probably the right place to start. The proposal is also interesting in its legislative designation of two “recreation areas,” taking these decisions out of the forest planning process.

The Lolo is scheduled to begin its forest plan revision process in 2023, and the Forest Service is also concerned about the interaction between the revision process and this legislation. It sounds like mostly a budgetary concern:

Our primary concerns pertain to Title II. Section 203 which would require the Forest Service to prepare a National Environmental Policy Act analysis for any collaboratively developed proposal to improve motorized and non-motorized recreational trail opportunities within the Ranger District within three years of receipt of the proposal… If passed in its current form, this bill could require recreation use allocation planning for site-specific portions of the Seeley Lake Ranger District ahead of the broader plan revision process, which would forestall the Lolo’s ability to broadly inform land use allocations across the forest through the plan revision process… If enacted, the explicit timeframes currently contained in the bill could result in prioritizing the analysis of a collaboratively developed proposal to expand the trail system over other emergent work.

But they might also be suggesting that the site-specific recreation planning would benefit from waiting until the forest plan is revised. (Or maybe they just don’t like deadlines.)