Ah.. “water conveyance structures”.. the expression rolls trippingly off the tongue, doesn’t it? I haven’t thought much about them since Colorado Roadless.

I thought that these op-eds were interesting, as the dry interior West, including national forest lands, are laced with these things. Now folks may have heard bad things about hydro, but the point of this article is that they are talking about existing structures, and the excessive needs of permitting, given that the additional environmental impacts are minimal.

Here’s an opinion piece in the Denver Post today. (non-Coloradans: the legislation the author discusses was around making rural energy providers have a renewable standard. Some saw it as urbanites imposing their ideologies on rural residents.)

The experience of George Wenschhof, a cattle rancher from Meeker, shows how a small-scale hydro project can be an economic boost.

Last week, during a national conference in Denver on hydropower, Wenschhof was something of a star.

He had used what he called “cowboy engineering” to install a hydroelectric turbine in an irrigation ditch on his property. It offsets the electricity he uses to run his ranch operation.

He saves somewhere on the order of $10,000 a year on electricity costs. He got a federal grant to pay for half the $160,000 project cost and state help with permitting. Deciding to go ahead was an economic decision.

Wenschhof figures it will take him eight years to make his money back, but the system could last up to 50 years with minimum maintenance.

“My hydro and my mule are going to outlast me,” he told me.

And Wenschhof is far from alone in having the right conditions to undertake a small hydro project.

Colorado is criss-crossed with irrigation ditches and canals — it’s one of the most irrigated states in the nation — and many of those provide opportunities for power generation.

The power from these small-scale projects can be used to directly power farm and ranch operations, or it could effectively be sold to the grid via net metering.

And the outlook for small-scale hydro is getting better.

The controversial SB 252 requires a small portion of that renewable energy — 1 percent — to be generated in what is called distributed generation, which is small, on-site power generation. Surely, that will encourage smaller projects.

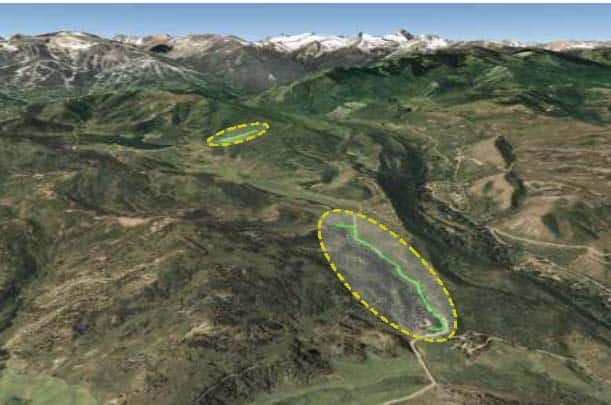

And the Colorado Department of Agriculture is engaged in a major effort to identify hydropower generation opportunities on ag land.

First, the department has commissioned a broad survey of the state’s irrigation waterways to identify the best sites. Fast-moving water and existing structures are key components. If the water already is traveling through a pipe, any adverse environmental impact was incurred long ago.

Also, the state is socking away a portion of severance tax proceeds — five years of up to $500,000 a year — to use as incentives to encourage the development of the most productive small projects, said Eric Lane, the Colorado Department of Agriculture’s conservation services director.

The other component that would help hydro projects take off is pending federal legislation to expedite permitting for smaller projects.

Right now, the cost of permitting sometimes outstrips the price tag for the power-generating equipment. That’s not smart policy for a nation that needs to encourage a range of sustainable energy sources.

All of these elements have the potential to make renewable energy policy, especially small hydro, a business opportunity for rural Colorado

I’m not so sure about granting individuals $80K so they save on their power bills, though. I’d rather buy solar panels for poor folks with it. But I wonder if that is really how the grants work, and if the bucks can be returned ultimately to the taxpayer somehow (extending the payback?). And granted, these are pilots to see what can be done.

There is also this editorial, also from the Denver Post, last weekend.

For years, hydroelectric power development has languished under the burden of stereotype: Its potential is tapped out. It’s detrimental to the environment. It’s not “real” renewable energy.

But legislation pending in Congress that could streamline the permitting process — without loosening environmental protections — might further unleash the power of this important energy source.

The measure has united Democrats and Republicans, environmentalists and utility representatives.

“Hydro is back,” U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, has exclaimed on more than one occasion.

And if this legislation is shaken loose in the Senate, that very well could be the case. The House version, co-sponsored by Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., already has passed the House unanimously.

You don’t have to be an energy geek to understand the positives of increased hydroelectric generation from existing dams and structures — no new construction required.

Of the 80,000 dams across the U.S., only 3 percent have electricity-generating equipment. The rest are dams that have water pouring over them every day without the flow being harnessed for energy production.

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy last year released a study that said without building a single new dam, the U.S. could boost its hydropower generating capacity by more than 12 gigawatts — or roughly 15 percent of hydroelectric generation — by optimizing existing structures. That means putting turbines on dams that don’t have them and upgrading technology at older dams to be more efficient and environmentally friendly.

For some perspective, hydro is the single largest source of renewable energy and supplies roughly 6.5 to 7 percent of electricity used daily in the nation.

A 15 percent boost is meaningful, and would help in other ways. One of the big benefits of hydro is that it’s a steady power source. Other renewables, such as solar and wind, are dependent upon conditions. Hydro is a “baseload” source that supports development of renewables with intermittent capacity.

The nut of the problem with hydro development now, even for simple projects on existing structures, is the lengthy and duplicative permitting process.

As it stands, the smallest and least intrusive projects, including those proposed by farmers to power irrigation systems, can take anywhere from six months to 18 months and a lot of hassle to permit. Larger projects can take up to eight years.

Here’s a paper with case studies.