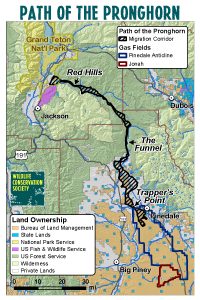

The Bridger-Teton National Forest amended its forest plan in 2008 to designate the portion of the “Path of the Pronghorn” migration corridor in Wyoming for special management to protect this historic 90-mile route with a northern terminus in Grand Teton National Park used for summer range. It’s probably the most significant action taken by the Forest Service to plan for wildlife connectivity.

The BLM chose to not play along at the southern end where major oil and gas fields are found in the species’ winter range, and the migration route lacks recognition, and protection, through BLM lands along its southern reaches. Now they have issued an EIS for oil and gas development there. Ideally, the EIS will disclose the effects on pronghorn migration and on the national park (using the best available science), which could include exterminating this migration and its pronghorn herd. But I wanted to comment on the planning aspect of this problem. BLM blames the State of Wyoming:

“It would help us out if the [Wyoming] Game and Fish were to formally designate something in there,” said Caleb Hiner, who manages the BLM’s Pinedale Field Office.

The Forest Service didn’t wait for state action to protect national forest lands. As an environmental activist said, “The BLM has all the authority it needs to protect what it wants to protect in a site-specific document,… The BLM could decide tomorrow that it doesn’t want to lease or develop any of the NPL.”

The 220-square-mile project has major economic potential, and could generate 950 jobs and produce somewhere in the range of 3 trillion cubic feet to 5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, Hiner said. It would add up to 350 wells to the landscape annually for the next 10 years, a level of development that equals the number of wells permitted for drilling in the BLM’s entire Pinedale Field Office during 2017.

The argument by the proponent seems to be that they can figure out mitigation well-by-well, but at that point there is little opportunity to develop an effective strategy for pronghorn to navigate the system of wells, especially with no plan-level requirement to do so.

It is important for federal land managers be leaders in coordinating connectivity conservation planning, if for no other reason that that may be what is necessary to provide for viable populations of migrating species to continue to use federal lands. The absence of a plan based on an overarching strategy for the full extent of the herd’s range could now be fatal to a ecological phenomenon that has been occurring, in part on national forest lands, for thousands of years.

Dead forests make very poor ‘connective’ habitat, for most rare species. It isn’t very ‘durable’. Hey, even black-backed woodpeckers can only use snag habitat for 6 years, before having to search for ‘fresher’ snags, elsewhere.

It seems to me that you can put in wells and not interfere with migration depending on where they are located. Perhaps that is BLM’s point. I would have tended to map the Pronghorn migration path and put that in the leasing analysis. Perhaps there is a reason they didn’t and asked the State to. Perhaps if they had done so they would have gotten into a discussion over where the lines should be, that is several stages before anyone would want to put a well anywhere specific, and they would like to postpone a theoretical battle until they have a proposal on the table with specific info. I can’t really disagree with that.

Plus I’ve seen pronghorn that appear to be happily grazing around gas wells as well as wind turbines.

The point of planning is exactly to get into “a discussion over where the lines SHOULD be, that is several stages before anyone would want to put a well anywhere specific” (my emphasis). A series of fine-scale, data-rich decisions can not substitute for making strategic decisions with broader-scale information. That is what NFMA/FLPMA is all about.

I get “postponing a battle,” but that’s a lazy way out that is not what is expected of federal land managers.

I see now that I didn’t link the article, which also discussed the science:

The paper, authored by Teton Valley, Idaho, biologist Renee Seidler, looked at pronghorn movement data and found that animals had an aversion to the already developed Anticline and Jonah fields, but liked the terrain free of drilling rigs further south. “In all years, probability of use during migration was high outside the areas of the densest gas field development and low inside the densest gas field development,” Seidler wrote in a paper titled “Identifying impediments to long-distance mammal migrations.” “In contrast, pronghorn used the undeveloped area of the proposed NPL project in all 5 years,” she wrote.

https://www.jhnewsandguide.com/news/environmental/article_2981c8de-541f-59f3-8f90-48fe810e0290.html