Still More Agreement About Fuel Treatment: Conservation Colorado and former Secretary Zinke

Sharon said:

That’s why I’m thinking that finding some projects that entail:

1. FS clearcutting in California

2. Fuel treatments in backcountry

3. Fuel treatments taking out big fire-resilient (living?) treesWould help us understand exactly what the issues are.

I think this project might be a good place to start:

Destructive wildfires along the California-Oregon border in recent years has the U.S. Forest Service pursuing projects to clear forests of burnt debris and trees that could feed future fires. One of those projects included selling the rights to log old-growth trees in Northern California, until a federal judge halted the timber sale on Friday.

Environmental groups asked a federal court to halt the Seaid-Horse timber sale in the Klamath National Forest. They say it would violate the Northwest Forest Plan by clear-cutting protected old-growth trees and harming Coho salmon.

Its purpose is: “Reduce safety hazards along roads & in concentrated stands, reduce fuels adjacent to private property, & to reduce the risk of future large-scale high severity fire losses of late successional habitat.”

So it’s got California, clearcutting, fuel treatment and big trees. It’s also got wildlife issues, which is the other point of disagreement I suggested. Maybe not back-country, but certainly not front-country – mid-country?

It even comes with a spokesperson who is probably familiar with our questions:

Western Environmental Law Group attorney Susan Jane Brown says old-growth trees in Northern California provide a habitat for threatened species such as the northern spotted owl. They’re also the most resilient in enduring wildfires.

“We could agree that cutting small trees is a good thing to reduce fire risk, but when it comes to cutting very large, very old trees, that’s an entirely different matter,” Brown said.

Thanks, Jon, for raising the issue of the Seiad-Horse project 🙂 It is merely the latest in a long string of legal challenges to post-fire logging of large diameter old growth trees from old growth reserves in the backcountry on the Klamath National Forest in northern California. This project also includes post-fire logging in riparian reserves, botanical areas, Inventoried Roadless Areas, and an essential wildlife corridor designated by the State of California, all located along the Siskiyou Crest.

While I am sure that there is disagreement on this blog about the need, utility, propriety, effect, and scientific basis for post-fire logging, perhaps this declaration that we filed to support our injunction motion will help put some of this in context (hopefully this link works for folks):

https://www.dropbox.com/s/6qz456b3av93xpc/Second%20Sexton%20Declaration%20-%20FINAL%20WITH%20EXHIBITS%20-%20SMALL.pdf?dl=0

The Forest Service vigorously opposed the filing of this declaration, and the Forest Supervisor argued that everything you see here complied with federal laws. Judge Nunley obviously disagreed.

The only thing I saw that was actually not ‘kosher’ is the landing within the stream buffer. Complaining about logging slash before the project is completed is unfair. How is the harvesting of some dead old growth something to worry about? How much old growth was left outside of the project, set aside for wildlife? Tractor ground goes up to 30%, and I did not see any slopes over that amount. I also did not see any examples of “clearcutting”, as is claimed. Is there an actual clearcut unit within the project’s plans? If it isn’t in the plans, then I don’t believe it happened.

That being said, wet weather operations should be closely monitored… by Forest Service experts, including Soils people.

Larry –

Large diameter snags (old growth) are incredibly important to wildlife and ecological function. From Dr. Jerry Franklin, one of the authors of the Northwest Forest Plan:

“Salvage logging of large snags and down boles does not contribute to recovery of late-successional forest habitat; in fact, the only activity more antithetical to the recovery processes would be removal of surviving green trees from burned sites. Large snags and logs of decay resistant species, such as Douglas-fir and cedars, are particularly critical as early and late successional wildlife habitat as well as for sustaining key ecological processes associated with nutrient, hydrologic, and energy cycles.

“Stand-replacement fires provide large pulses of coarse woody debris (CWD) including snags and logs, which lifeboat dependent species and processes until the regenerating forest begins to produce large and decay-resistant dead wood structures, which is typically not for a century or more. Since this pulse provides all of the large CWD that is going to be available to the ecosystem for at least the next I 00 to 150 years, it is not appropriate to use the levels of CWD found in mature and old stands of a particular Plant Association Group (PAO) as a guide to levels of CWD that should be retained after salvage. Effectively none of the large snags and logs of decay-resistant species can be viewed as being in excess of what is needed to assist in natural recovery to late-successional forest conditions and, hence, appropriate for salvage on land allocations where ecological objectives are primary, such as LSRs. Retention oflarge snags and logs are specifically relevant to Northern Spotted Owl (NSO) since these structures provide the habitat that sustain most of the owl’s forest-based prey species.”

Some of the stumps you see in the photo are from roadside hazard tree removal (which we did not oppose in the litigation), but not all of them: some are deep inside harvest units. Indeed, the Forest Service acknowledged that the average diameter of tree removed from salvage units was in excess of 14″ DBH and most much greater than that. In this landscape, those are “big trees” (and represent snags “likely to persist until the next stand is again producing snags,” the operational language from the Northwest Forest Plan).

The Forest Service also acknowledged that all of the large diameter trees would be removed (except those in no-harvest areas at the edge of units), leaving behind the small diameter trees that are not merchantable but also contribute to future fire risk. The resulting landscape is one that is devoid of the large tree structure of the previous stand, and is more flammable than before or after the fire.

I make no apologies about my general opposition to post-fire logging, but I have room for the belief that it can be done in a way that protects wildlife, soils, and aquatic resources while also producing a commercial by-product that doesn’t leave the landscape more vulnerable to future wildfires. But the Seiad-Horse project (or recent others on the Klamath) are not that.

So, are you willing to go under oath to say that none of the stumps in the pictures are close to roads or landings, and that the court should stop what they see in these pictures? I’m also quite sure that there are existing snag retention guidelines, too. Are they not meeting those specifications? Do you have actual evidence that can be presented in court, under oath? Will you also say, under oath, that there are illegal clearcuts being created (despite the clear presence of trees still standing)? Finally, one last question. How much of the wildfire is actually within the project’s boundary? (Maybe that burned area outside of the project is being used solely for wildlife issues?)

I do feel that if the project is stopped, for now, that erosion control measures should be in place, immediately. If not, why not? The wet weather operating plan could be a good document to have, for review and monitoring.

Larry –

I would not be willing to “go under oath” as you say, because I personally haven’t visited the site and seen it with my own eyes. But, my clients have been there, and have seen it, and have so sworn in declarations filed in federal court under penalty of perjury.

The lawsuit is partially about whether the Forest Service met the applicable snag retention guidelines. Judge Nunley held that they did not.

The Abney fire burned about 10,800 acres on the Klamath National Forest, and about 1,100 acres was proposed for harvest in the Johnny O’Neil Late-Successional Reserve (and Kangaroo Inventoried Roadless Area, Cook and Green Botanical Area, designated northern spotted owl critical habitat, California State Essential Habitat Connectivity Area, Riparian Reserves, and adjacent to the Pacific Crest Trail).

Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) treatments immediately after the fire stabilized slopes, and addressed some of the more problematic roads in the watershed. The California Water Board has also been monitoring implementation.

Susan Jane

I’m just not seeing ANY evidence of clearcutting in the photos. Sooo, he has sworn that he has seen clearcuts, but he…. neglected…. to take pictures?!?!? I just don’t see much evidence of ANY of the claims in the accompanying the pictures. Don’t the burned snags outside the project count for anything?

I really do think that entire burned areas should be included in the EA/EIS, so that excluded areas can count towards requirements. It may take a little longer to compile but, I think it would help in defending the project in court.

Larry –

Check out this map showing the Low Gap timber sale, where the photos were taken. The cross hatched areas (designated as “Site Specific Protection Measure (Snag Retention), B6.24, C6.24#” show where snags are to be retained. Many units have no snag retention areas, and the ones that do have those areas generally pushed to the edge of harvest units. As a result, any large diameter snags that are retained are generally not part of harvested areas, leaving them devoid of snags.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd597793.pdf

Although the literature recommends clumping snags for wildlife, it also indicates that areas that have no snags are not viable habitat for most species that require this habitat feature.

This area seems to be one of the spots in question. https://www.google.com/maps/@41.9042743,-123.0903033,1353m/data=!3m1!1e3?hl=en

It sure seems like they could have left ample snags, to meet the rules. (Be sure to zoom in and look at how much is there) When I administered salvage sales, I just assumed that eco-groups were monitoring, whether there were, or not. I always wanted to ‘walk the talk’.

I remind people that only the Klamath, Shasta-Trinity and Six Rivers (and maybe some Forests which slop over the border from Oregon) NF’s fall under the Northwest Forest Plan, in California. All the rest of California’s National Forests continue to ban clearcuts and large tree harvesting (Yes, in the size spectrum of ponderosa pines, 30″ dbh is not a “large tree” )

Thanks to Jon for this post, and to Susan Jane Brown for the additional information and context. I do hope folks will click on the link to the declaration that Susan Jane provided. If not, I’ll post the first four photos from that declaration right here:

Soooo, going back to what Sharon said, I see no clearcutting involved, nor any “big fire-resilient (living?) trees” being cut. Salvage projects have different purposes and needs than a fuels project. This smells like complaining about salvage logging, in general. I’m also guessing that every large stump in the pictures was near a road or landing, and is perfectly mandated to be cut for safety, as per OSHA rules and the standard timber sale contract.

This is a great discussion IMHO because we are discussing a real sale and real trees!!! Thanks to everyone participating, especially Susan. I think every new person we bring to this discussion helps all of us understand. I do have some questions..

“The Forest Service also acknowledged that all of the large diameter trees would be removed (except those in no-harvest areas at the edge of units), leaving behind the small diameter trees that are not merchantable but also contribute to future fire risk. The resulting landscape is one that is devoid of the large tree structure of the previous stand, and is more flammable than before or after the fire.”

1) if you have lots of snags, how does a wildlife biologist decide how many are “needed”? Conceivably if there were some amount of snags before, wildlife were doing OK. Now there are a lot more. Is it better to leave the old ones, that might be closer to falling down, or the new ones, or some mix? How many are “enough” (all??) and how does a wildlife bio think about this? (For all I know there might be a requirement in the NW Forest Plan for a retention size/number of snags per acre, so that would be interesting information also.)

2) If there are large dead trees and small dead trees, I think you could make an argument that removing the large ones reduces the total fuel load on the site. It does seem to me that removing dead small ones also would be good for to reduce future fuels but a) why would “smaller dead trees only” be worse fire-wise than a “mix of large and small dead trees”? and of course b) there is a market for larger trees to help pay for the treatment. Logically if you have a (dead small trees) plus b (dead large trees)= c (total fuel loading) then you could reduce a or b to reduce c. If the goal is to reduce c, then reducing a or b or a combination would get you there. I’m not there with if you reduce b, but not a, you are not helping and actually making things worse.

3) That being said, it still seems that in the case the question is “how many large snags should be left?” and plenty of room to agree between zero and all.

These are all good questions, and ones that we addressed in the course of litigation (maybe I should upload our briefs??). There are a couple of issues I’ll try to unpack.

There is a Klamath LRMP snag retention requirement that applies to cavity excavators (woodpeckers) and allows the USFS to average snag retention across 100 acres; many forest plans have similar requirements.

However, the Northwest Forest Plan, which amended the Klamath LRMP and is directly applicable to site-specific projects, does not use that approach. Instead, within Late-Successional Reserves, “following stand-replacing disturbance, management should focus on retaining snags that are likely to persist until late-successional conditions have developed and the new stand is again producing large snags. Late-successional conditions are not associated with stands less than 80 years old).”

Thus, the question becomes whether salvage prescriptions “focus on retaining snags that are likely to persist,” or not. This language is NOT “retain ALL snags” but nor is it “retain only a few snags.” Where the agencies get in trouble is by removing almost all large snags from harvest areas, or “retaining” snags in unharvested areas.

The NFP also says that in post-fire environments in LSRs “while priority should be given to salvage in areas where it will have a positive effect on late-successional forest habitat, salvage operations should not diminish habitat suitability now or in the future.” In the Seiad-Horse EA, the agency was candid that removing large diameter snags would set back wildlife habitat needs not only for woodpeckers, but also northern spotted owls, fisher, goshawk, wolverine, marten, and other species. Because this NFP provision speaks to other species than just woodpeckers, the Klamath LRMP provision that allows snag averaging over 100 acres does not apply (because that provision only applies to cavity excavators, and these species are not cavity excavators).

The Ninth Circuit squarely addressed these issues in Oregon Natural Resources Council v. Brong, 492 F.3d 1120 (9th Cir. 2007), which analyzed a BLM salvage sale in Oregon, also in Late-Successional Reserves. The opinion is available here: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-9th-circuit/1478158.html.

The ultimate answer to the question about how many snags are necessary for wildlife is nuanced, and depends on the critter as well as the forest type at issue. My reading of the literature is that it generally concludes that most landscapes are depauperate in large diameter snags, even in this era of increased wildfire and insect and disease disturbances. That may change over time, of course. But today, wildlife still need large snags of different species, hardness, spatial arrangement, etc., and management that targets these snags for removal should be discouraged. The work of Evelyn Bull, Dick Hutto, Vicki Saab, and John Dudley is fairly clear about this conclusion.

I do agree that large snags make much better wildlife habitat than smaller snags. If it were up to me, loggers would get some of the bigger snags, as long as they take most of the smaller snags. However, that would require getting into the projects as quick as possible, so that the small diameter wood is still good. I worked on a salvage project on the Winema, where the smallest ‘commercial’ log was 7 inches dbh, 8 feet long, to a 5 inch top. It could be done, back then, with lower transportation costs. Imagine seeing a log truck with over 200 of those small logs on it!

Thanks, I would appreciate that, Susan. I guess there are two ways to look at this.. strictly on the biology/ecology. Snags are good, downed woody material is good, but is every snag or piece of downed woody material essential to ecosystem function?

“generally concludes that most landscapes are depauperate in large diameter snags, even in this era of increased wildfire and insect and disease disturbances. ” But the question is not “most landscapes” it would be “this landscape” and we can imagine some places are snagfests and others with fewer snags than (the past? what was optimal?). I wonder whether some of these large scale decisions such as the NWFP are simply on too grand a scale to identify key ecological differences in different parts of the area covered.

Here’s another question…in at least one objection response letter, it said

“The project is consistent with Northwest Forest Plan and Klamath National Forest Land

Management Plan (Forest Plan) direction concerning snag dependent species.”

https://www.fs.fed.us/objections/objections_list.php?d=2&r=110500

So basically it sounds as if you and the FS disagree about whether you are following that direction? I would like to see your briefs and also the Government side. Somehow I have difficulty obtaining the latter, even when plaintiffs are kind enough to provide me with the plaintiff briefs.

I looked up Hutto’s bio and it said “His current project involves ‘getting the fire management community to draw from the evolutionary history of plants and animals to learn how to properly manage disturbance-dependent conifer forest communities.'”

Sounds like he and I should agree on things since I am also a plant evolutionary biologist. But I guess I wouldn’t feel that my background enables me to discern what is “proper” fire management. I think I would take into consideration the needs of humans, wildlife, plants and of course the expertise of fuels specialists and suppression folks. But that’s jsut me ;).

You can access briefs filed electronically in federal court by using PACER, which requires a subscription but many downloads are free: https://www.pacer.gov/. You can search by party, case number, date, and other parameters.

Plaintiffs’ opening TRO brief is available here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/oep12v0c7xbm776/CORRECTED%20Seiad-Horse%20Memo%20ISO%20TRO-PI%20-%20FINAL.pdf?dl=0

Government’s response: https://www.dropbox.com/s/fflrn7ltbnfyv4i/DOJ%20Response%20to%20Motion%20for%20TRO.pdf?dl=0

Plaintiffs’ reply: https://www.dropbox.com/s/wop3ujk3wgte9sm/Seiad-Horse%20TRO-PI%20Reply%20-%20FINAL.pdf?dl=0

Government’s reply: https://www.dropbox.com/s/98hidr7mgwcs58z/DOJ%20Reply%20in%20Opposition%20to%20TRO-PI.pdf?dl=0

Thanks, Susan, I used to be able to access Pacer when I was working for the FS, but didn’t understand that some of them are free. That’s great information!

Here’s what I found about the snags in the EA (hopefully this is the correct one):

https://www.fs.usda.gov/nfs/11558/www/nepa/108129_FSPLT3_4283401.pdf

Is this the part of the project that there is a disagreement about?

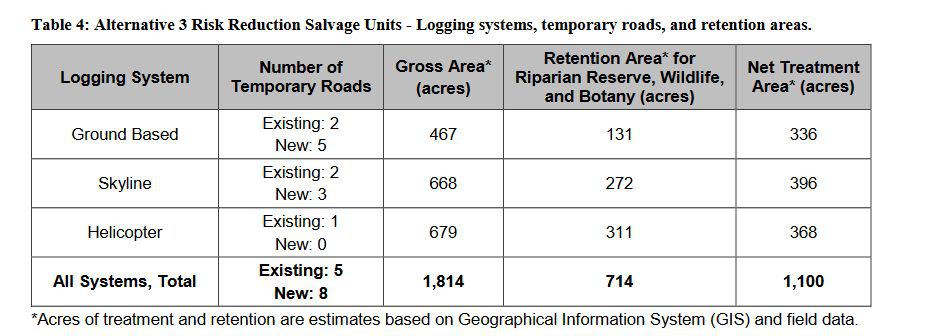

Note that this is 1100 spread-out acres (based on the existence of retention areas) within the 10K acres burned on the Klamath.

“Standing dead trees 14 inches in diameter at breast height or greater would be considered for salvage using the guidelines in Report #RO-11-01 “Marking Guidelines for Fire-Injured Trees in California” (Smith and Cluck 2011). Fire-killed and fire-injured trees with a 70 percent or greater chance of dying within the next three to five years would be considered for risk reduction salvage harvest. Trees identified as hazards using Report #RO-12-01, “Hazard Tree Guidelines for Forest Service Facilities and Roads in the Pacific Southwest Region” (Angwin et al. 2012) along roads and within salvage units would be felled to abate the hazard.

Snags for wildlife would be retained based on 100-acre landscape areas according to numerical and diameter standards in the Forest Plan (p. 4-26). In any 100-acre area, snags within and outside risk reduction salvage units may contribute to these standards. Within harvest units, snags would be retained in all riparian reserves (stream, active landslides and inner gorges) and in clumps in designated snag retention areas as necessary to meet these standards (wildlife and botany). Individual snags within harvest units would not be retained unless they have high quality habitat characteristics such as signs of decay and defect, cavities, broken or multiple tops, or very large lateral branches and flattened canopy.

In order to contribute to Recovery Action 12 (USFWS 2011), very large snags that have these

characteristics and are likely to persist until the next stand is capable of producing large snags should be retained wherever they occur, provided they do not pose a safety risk to forest workers. If a wildlife snag must be felled for safety reasons, the entire tree would be left in place and shall not be bucked into smaller logs. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show examples of snags with these wildlife characteristics that would be left in the risk reduction salvage units.

Risk reduction salvage harvest treatments would be accomplished by a combination of ground-based, skyline, or helicopter logging systems. All salvage units would be site prepped and reforested as described in the site preparation and planting section below.

Salvage is only proposed within the late-successional reserve management area. The potential for benefit to species associated with late-successional forest conditions from risk reduction salvage harvest is greatest when stand-replacing events are involved. Salvage in disturbed sites of greater than 10 acres and where the disturbance reduced live canopy closure is less than 40 percent is included (Forest Plan MA5-30(1), pg. 4-97). No salvage harvest is proposed within inventoried released roadless areas, backcountry wilderness management area, or hydrologic riparian reserves.”

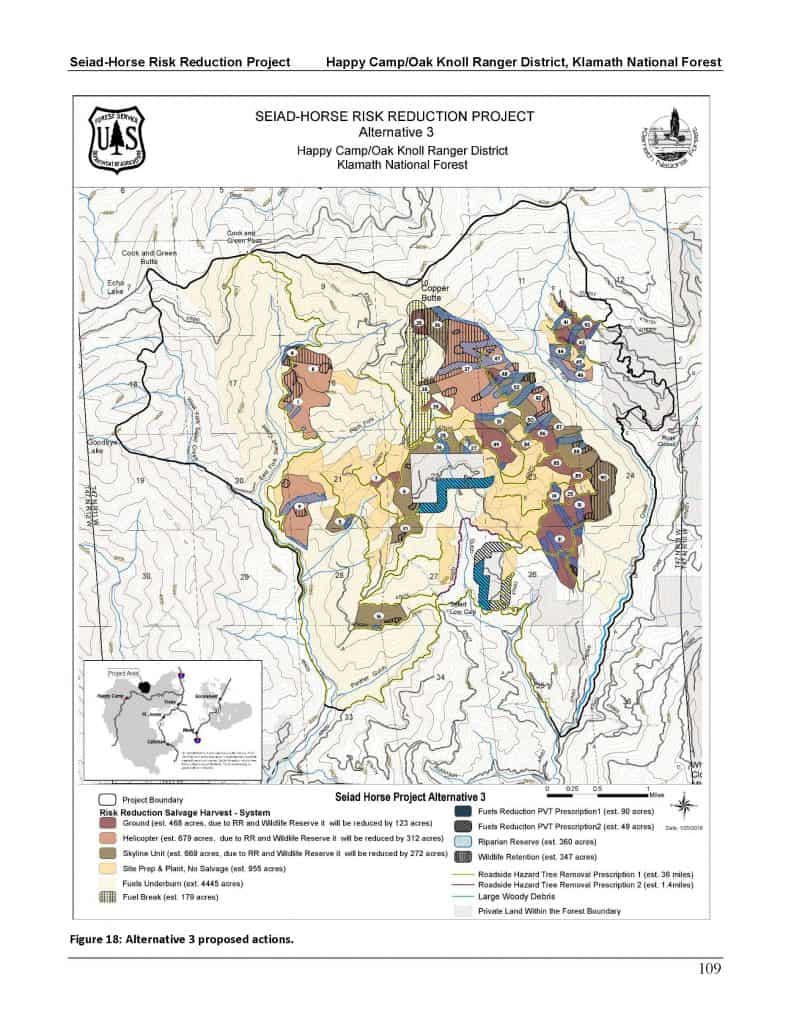

Here’s a map:

This seems similar to the Biscuit Fire salvage, where I helped mark the snags to be left standing. We followed the guidelines to the letter, even marking HUGE sugar pines, well over 50 inches in diameter. Extreme insect mortality occurred after our work was done, and the loggers probably got a nice windfall, as the logging proceeded.

Of course, not every acre will have wildlife trees, under the current guidelines, and that is perfectly fine. To be honest, I did not see any huge wildlife trees in any of the pictures. I attribute that to the presence of roads and clumping of snags. I’m also skeptical of the claim that spotted owls use snags in burned areas for anything other than perching. Forest Service Wildlife Biologists don’t think that snags in burns add anything to owl’s ‘habitat’. So, how does deference to Agency scientists figure into this situation?

Additionally, as always, bark beetles will be adding more snags of ALL sizes, especially in the fringe areas of the burn, which are not within the project area. That reality SHOULD be addressed but, it never really is mentioned in EA’s.

Larry Said: “I’m also quite sure that there are existing snag retention guidelines, too. Are they not meeting those specifications?”

Larry did not say:

A Guide to the Interpretation and Use of the DecAID Advisor, June, 2006 http://www.fs.fed.us/r6/nr/wildlife/decaid-guide/ [Note: The snag standards in the Northwest Forest Plan were also based on the discredited potential population methodology, and neither R6 or R5 have prepared a plan amendment to update their snag standards based on new science indicating that more snags are needed.]

Soooo, yes, I was correct in what I said, then. Of course, EVERY salvage project has guidelines.

Larry said: “Salvage projects have different purposes and needs than a fuels project.”

Larry did not say:

Northwest Forest Plan standards & guidelines for salvage logging in Late Successional Reserves.

And the 2011 Final Revised Recovery Plan for the northern spotted owl says:

Note also, the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan ROD (page C-11, and 1994 FSEIS page F-146) says that ” … activities required by recovery plans for listed threatened and endangered species take precedence over Late-Successional Reserve standards and guidelines.”

Of course, 2nd Law did NOT say that current salvage logging practices harvest tiny chunks of burned areas, these days. This Abney Fire was 10,000 acres but, only about 1000 acres are being harvested. And snags are being left in the harvest units, as can be seen in the plaintiff’s pictures.

After reading the court opinion …

While this is a project is an example involving fuel treatments and the ecological value of dead trees, it turns out the legal issue is whether the Forest complied with the existing forest plan requirement for dead trees, including: “focus on retaining snags that are likely to persist.” The court said (for the purpose of a preliminary injunction) that it doesn’t look like the Forest had followed this direction. Here’s what the court said:

“Here, the EA on its face states, “substantial amounts of habitat are projected to be degraded by the proposed actions.” (EC at 113.) While the EA explains that this will not affect the viability of the northern spotted owl in the long-term, it does not appear to explain whether the current habitat suitability will be maintained, as required by the NFP, other than stating that the viability of the species as a whole will be maintained.”

The key holding in the Brong case cited by this court was this: “it neglects to explain why the snag removal it does authorize, which [i]ndisputably harms late-successional habitat in the short term, will somehow maintain overall habitat suitability now or in the future, as expressly required by the NFP.” While the holding in both cases is “did not explain,” it appears this court is skeptical that the Forest Service would be able to explain why removing large snags is ok.

If the best available science says that removal of any dead or dying wood reduces the long-term habitat value (as suggested by Susan Jane’s and 2ndLaw’s references), it would not be possible to salvage in LSRs. Presumably this science incorporates the risk of reburns to habitat. At best, it looks like the NFP language that says, “salvage in areas where it will have a positive effect on late-successional forest habitat” would only be applicable to snags that would not “persist.”

To Larry’s question about snags outside of the project, the Brong case also determined that, “BLM’s practice averaging “salvaged and non-salvaged areas together across all the acres included in the logging” to claim the snag retention was “enough” under the NFP was misleading,” and that the NFP standard applies to harvest units. While the Klamath Forest Plan also has language applying snag requirements to 100-acre landscape areas, that doesn’t replace the NFP requirements for spotted owls.

That would also be my take, on this specific issue. The LSR’s have different requirements, and they do overrule other ‘purposes and needs’. Regarding the last paragraph, I see there could be room for misusing the averaging thing, over an entire burn. Using formerly-brushy acres in ‘averaging’ is like comparing apples to grapes. If you are going to average acres, you should be using timbered acres, and excluding acres outside the project that do not have worthwhile snags. The intent of averaging should be to still have the required amount of snags, as well as the quality of that habitat. The rules (and intent) regarding salvage in the LSR’s seems clear to me. Averaging in the LSR’s need to be exclusive. You cannot supply clumps of smaller snags outside the LSR, in exchange for cutting heavier within it.

Thanks for reading this, Jon! These decisions can be impenetrable.. I am confused and I think it’s by the court and not you. You said-

“the legal issue is whether the Forest complied with the existing forest plan requirement for dead trees, including: “focus on retaining snags that are likely to persist.” The court said (for the purpose of a preliminary injunction) that it doesn’t look like the Forest had followed this direction.”

OK, in my simple world, “focus” is kind of generic. It doesn’t say “retain all”. It doesn’t say “retain some but not all.” I could even read it as “if you leave snags, focus on leaving the ones that are likely to stay around”. How did the court interpret it?

But then you said…

“Here, the EA on its face states, “substantial amounts of habitat are projected to be degraded by the proposed actions.” (EC at 113.) While the EA explains that this will not affect the viability of the northern spotted owl in the long-term, it does not appear to explain whether the current habitat suitability will be maintained, as required by the NFP, other than stating that the viability of the species as a whole will be maintained.”

But that doesn’t sound like it’s about the Forest Plan, it’s about the NFP and habitat “current habitat suitability” for NSO? I’m confused.

As to “The key holding in the Brong case cited by this court was this: “it neglects to explain why the snag removal it does authorize, which [i]ndisputably harms late-successional habitat in the short term, will somehow maintain overall habitat suitability now or in the future, as expressly required by the NFP.” While the holding in both cases is “did not explain,” it appears this court is skeptical that the Forest Service would be able to explain why removing large snags is ok.”

I know that there is conflicting literature about fuel treatments and spotted owls, depending on various assumptions, part of the country and so on. The idea is not complex. If you have late successional areas that might get burned up, and you can manage fires better with treatments designed to foster fuel conditions where you can suppress the fire better before it gets to the prime LS habitat, then indeed it can maintain overall landscape scale habitat suitability in the future. Maybe the FS did not make this case well. But maybe it did and the court chose not to believe them.

It takes the FS all most a year to put up fire salvage sales, and maybe another year before you can actually operate the sale. Most small diameter trees, especially the white woods are noncommercial by that time. This is unfortunate because the industry is really set up for small diameter trees. So most small diameter trees are cut down and left. Much of the industry doesn’t want anything to do with burnt wood.

This is a catastrophic waste of our natural resources. It makes me so sad to see these forests we think are so important to conserve destroyed by the “let it burn” philosophy.

A salvage sale may be a 1,000 acres in size, but actuality maybe a couple hundred acres are harvested. The boundaries are always but larger than the harvest units. Out of all the fires in northern California and Southern Oregon I would be surprised if more than 1% has been harvested on public lands.

Don’t worry there are lots of large dead burnt old snags out there and unharvested ground.

We can continue to debate the best management for spotted owl habitat (presumably as part of revising the plans, and I guess the science work for that has already been done), but this court was only deciding whether the project complied with current plan requirements for management of spotted owl habitat in burned areas.

I agree that “focus” is not good forest plan language, but it sounds like “ignore” does not qualify as “focus.” The other plan language that seems most relevant (only looking at what the court apparently looked at), was “salvage operations should not diminish habitat suitability now or in the future.” So maintaining “current habit suitability” is part of the plan. If the case proceeds to summary judgment, it’s possible the FS could convince the judge that this isn’t really what the plan means.

…And in our view, that would be tough, since the Ninth Circuit has already held that maintaining current habitat suitability (now or in the future) is exactly what the Northwest Forest Plan requires. See: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-9th-circuit/1478158.html