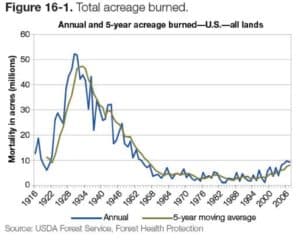

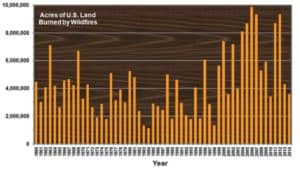

We’ve all heard about the dramatic increase in U.S. wildfire acres burned:

Oops! Wrong graph. Here’s the correct one:

Many attribute this trend to increases in atmospheric greenhouse gases. Another factor is how we manage wildland fire, as discussed by two firefighters. Travis Dotson is an analyst at the Wildlands Fire Lessons Learned Center, while Mike Lewelling is Fire Management Officer at Rocky Mountain National Park.

TRAVIS: Overall, what would you say are the biggest positive changes you’ve seen in our culture during your entire career?

MIKE: I think we are more mindful about how we manage fires now. I saw a map side-by-side of all the fires from the early 80s into the 90s and it’s all these little pinpricks of fires. And then you go into the 2000s to now and the footprints are a lot bigger. There’s a lot that goes into that. But I think part of that is not always throwing everything at every fire. Mother Nature uses fire to clean house and it doesn’t matter what we do, she’s going to do it eventually. So whether we put ourselves in the way of that or let it happen is an important decision. I think that, overall, risk management—how we respond to fires—is a significant advance.

TRAVIS: For sure. I’ve seen research showing that the best investment we can make is big fire footprints. That is what ends up being both a money saver and exposure saver down the line as well as an ecological investment, obviously. For so long, large fire footprints were only being pushed from an ecological perspective and now we’re talking about the risk benefits of changing our default setting away from just crush it. There is often an immediate and future benefit on the risk front (less exposure now AND a larger footprint reducing future threat).

The first graph goes back only to 1916. This paper goes much farther back: “Fire Episodes in the Inland Northwest (1540-1940) Based on Fire History Data,” by Stephen W. Barrett, Stephen F. Arno. and James P. Menakis, USFS 1997.

Research Summary

Information from fire history studies in the Northwestern United States was used to identify and map “fire episodes” (5 year periods) when fire records were most abundant. Episodes of widespread landscape-scale fires occurred at average intervals of 12 years. Mean annual acreage burned was calculated based on estimated areas of historical vegetation types with their associated fire intervals from the fire history studies. An average of about 6 million acres of forest and grass and shrubland burned annually within the 200 million acre Columbia River Basin study region, and especially active fire years probably burned twice this much area. For comparison, the largest known fire years since 1900 have each burned 2 million to 3 million acres in this region. We also compare the occurrence of regional fire episodes to drought cycles defined by tree-ring studies. [emphasis added]

Here are some more charts and wildfire figures. Much of this information was systematically purged from various agency websites during the George W. Bush years, when former timber industry lobbyist Mark Rey was under-secretary.

When Travis says: “I’ve seen research showing that the best investment we can make is big fire footprints. That is what ends up being both a money saver and exposure saver down the line as well as an ecological investment, obviously” does anyone know what research he may be referring to? I’m sure I’ve seen something along those lines, but don’t have relevant studies at my fingertips. Thanks!

Rolf, the people in my neighborhood (Colorado Springs, CO) tend not to think that “big fire footprints” around here are “money savers”. I think Travis might be talking about “big fire footprints in uninhabited areas.” Which would lead us to ask the question, where are those and how many of those areas exist? Also, I’d question what he means by “ecological”.. some fires are not so good for tree species (no nearby seed sources, or requiring investments to get trees back). Why are fires good “ecologically?” Possibly to develop conditions that people who are fans of certain conditions like (open park-like stands of p pine) or to represent certain points in history. You only have to look at the plethora of fire acreage charts, to think that picking a point in history that is appropriately “ecological” is difficult and ultimately just another human value judgment (under the mantle of HRV, NRV,”reference conditions” or whatever).

Letting fires burn is not ‘cheaper’ than attacking them, when they are smaller and less intense. Turning a $8000 lightning fire into a a $100,000,000 firestorm (like the West Fork Incident in Colorado) is not a good idea, regardless of any perceived “natural and beneficial” effect. PLUS, you cannot put a price on the loss of endangered species habitats that are often incinerated in such wildfires.

Then… there is also the fact that post-fire costs are usually many times the suppression costs, especially when humans are impacted.

It sure looks like the State of California wants to invest in their forests. The Forest Service is keeping busy but, not making a dent in the amount of fuels on their Federal lands. A few thousands of acres every year isn’t going to get the job done in a timely manner. Uncontrolled fire will continue to be the biggest impact on California ecosystems, and the humans who love them.

It also looks like the Rockies will have their own problems with their own dead forests, and wildfires. We should continue to see weeks-long firestorms, impacting humans in multiple terrible ways.

Might be useful to distinguish between large fire footprints when weather conditions are more favorable to low and mixed fire, rather than large fire footprints from wildfire burnout operations when the weather is hot, dry and windy.