Everyone has heard of basic and applied sciences. Generally, basic is thought to be better by scientists, and applied, more useful by others. But why is this, and how does it affect how we affect the practice of science today? First, let’s return to Peter Medawar.

The hard and fast distinction between pure and applied science is a quaint relic of the days when it was widely and authoritatively believed that axioms and generative ideas of some privileged sciences (the ‘Pure’ Sciences strictly so called) were known with certainty by intuition or revelation, while the Applied Sciences grew out of merely empirical observations concerning ‘matters of fact or existence’. The distinction between pure and applied science persisted in Victorian and Edwardian times as the basis of a class distinction between activities that did or did not become a gentleman (‘Pure Science’ being a genteel occupation and ‘Applied Science’ having disreputable associations with manual work or with trade). This class distinction is now widely believed to have been rather damaging to this country.

Medawar also argued strongly in the 70’s that basic and applied funding decisions needed to be made by scientists, and not users of science. Here’s a link to a history paper on this. It did not go without notice by others that the position of scientist must make all funding decisions about science is a bit self-serving for something funded by tax dollars. But what does this have to do with us today?

A few months ago, I attended a Forest Service Partners shindig and ran into a person in Forest Service R&D. I asked him how things were going, and he said Congress was on his back about not funding useful research. Of course, this has nothing to do with FS R&D as currently constituted, but has been an ongoing tension for as long as there has been serious levels of public funding for scientific research, and not just in the US. (This is my version of history and others are invited to add their own perspectives and experiences).

The Fund for Rural America was an attempt by Congress to convince researchers to do useful things for rural Americans. You can check out the provisions of the 1996 Farm Bill here (note that the same conversation was close to 25 years ago):

(C) USE OF GRANT.—

(i) IN GENERAL.—A grant made under this paragraph may be used by a grantee for 1 or more of

the following uses:

(I) Outcome-oriented research at the discovery end of the spectrum to provide breakthrough results.

(II) Exploratory and advanced development and technology with well-identified outcomes.

(III) A national, regional, or multi-State program oriented primarily toward extension programs and education programs demonstrating and supporting the competitiveness of United States

agriculture.

Notice the “outcome-oriented.”

Yet, let’s look at the other forces pushing toward basic research. Here’s a 2014 report from the National Academy of Sciences.

USDA has played a key role in supporting extramural research for agriculture since the passage of the Hatch Act in 1887, but its use of competitive funding as a mechanism to support extramural research began more recently (see Figure 3-1). A peer-review competitive grants program was proposed as a means of moving a publicly funded agricultural research portfolio toward the more basic end of the R&D spectrum.2 A 1989 National Research Council report stated that “there is ample justification for increased allocations for the [competitive] grants program to a level that would approximate 20 percent of the USDA’s research budget, at least one half of which would be for basic research related to agriculture” (NRC, 1989, pp. 49–50).

The National Research Council study (part of the National Academies, what I call the Temple of Science) pushed toward more basic research. Why 50% of the total? I’m sure they have a rationale, but not sure that the Congress would agree. So again, we see the Science Establishment going for more basic (and potentially less utility and accountability) and Congress later pushing back asking public funds to have more accountability (outcome-oriented).

I also had a ring-side seat for part of a transition. At one time USDA had (more) formula funds that were given to land grant schools to figure out useful things. Often for forest science, the Dean would get together users and others to help prioritize research via discussions at the state level, at the best. Or perhaps give it to his buddies or use it as trade for something, at the worst. But then USDA-CSREES now NIFA hired a bunch of folks from the National Science Foundation, who came with the idea that only scientists can judge whether research is worth doing, and the best way is to bring them together for panels in DC. The FRA staff, including me, even got in trouble with the Powers that Were for allowing a user on a panel.

Meanwhile, back at the Forest Service, Forest Service scientists were less funded, and told to look for funding elsewhere than the Forest Service, which necessarily led them to focus on what other scientists who run grant programs think is cool.

If we go back to the history paper above, we can see that politicians can see the self-interest of scientists in this, but it has nevertheless been difficult for politicians (even appropriators!) and the public to get a grip on it. Of course, agriculture, health, nutrition, engineering, and different technologies have different communities, funding sources and approaches, so the applied sciences, like science in general, are not one thing.

If something is useful, then framing the question (as we’ve seen, extremely important in figuring out which disciplines and approaches are helpful) should definitely be done including users (in our case, practitioners, land managers and so on). I’m not saying that researchers don’t do this through their own personal commitment- I’m saying that the systems in place do not necessarily support it and could be changed to support it.

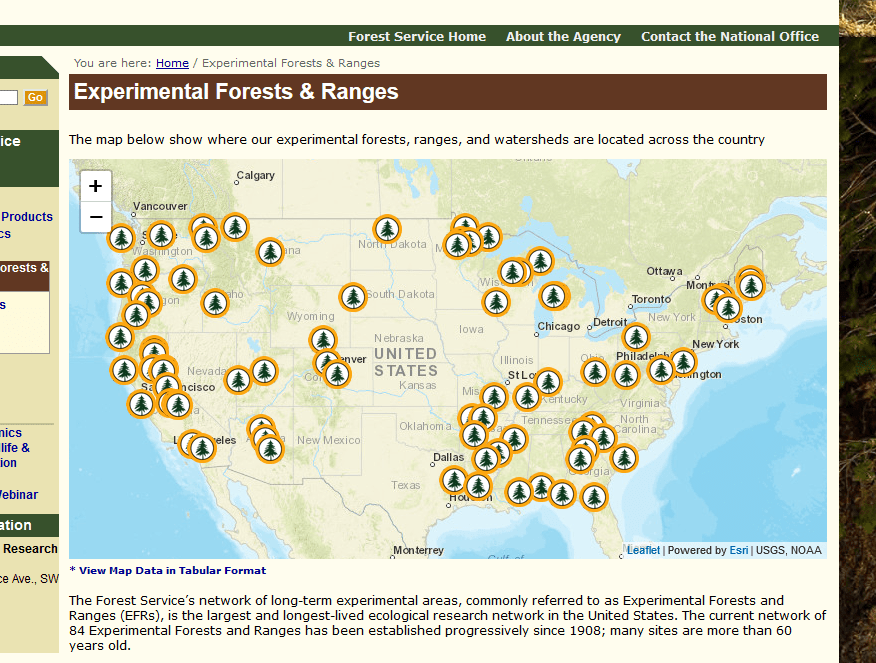

Another tendency is for departments to centralize scientists (e.g. USGS), which can also drive them farther away from research that helps their agency colleagues. IMHO the Forest Service was wise, politically astute, and/or lucky to retain their own research scientists, even if it leads sometimes to intramural drama. A small price to pay for a modicum of independence from the Science Establishment.

“Everyone has heard of basic and applied sciences. Generally, basic is thought to be better by scientists, and applied, more useful by others. But why is this, and how does it affect how we affect the practice of science today?”

===

Our world is loaded with 10s of 1000s of people who are book smart, but not practical application smart. So when you say, ” . . basic is thought to be better by scientists, and applied, more useful by others,” our planet’s degradation is a testimony to this fact.

Maybe it’s testimony to the fact that most investment in science is going to be applied to things that make money, and things that make money tend to ignore what they do to our planet. Maybe science by government researchers is a different story, though.

This your turf, Sharon, but I’m guessing there is more to the argument for basic science than “self-serving” scientists. It would be interesting to compare the societal benefits of what basic and applied science have produced.