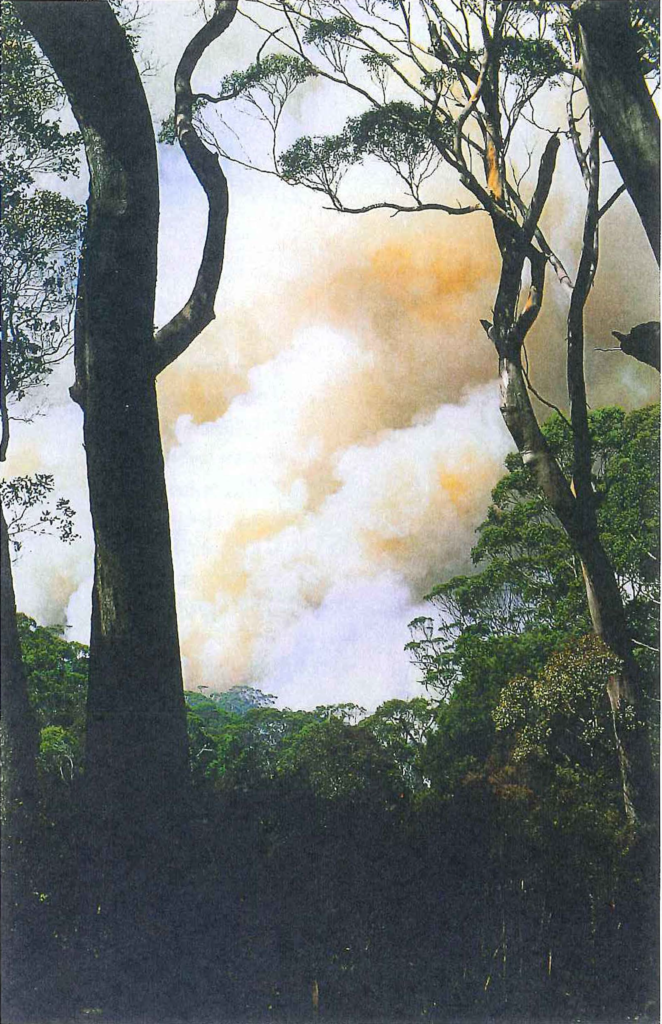

Photo – Jiri Lochman

As the world’s attention has turned to the tragedies of the recent and ongoing Australian bushfires, it has been an opportunity for some of us to learn about bushfires, their history, and how Australians have handled them and perhaps compare their history and solutions to our own.

One theme that has been reoccurring on The Smokey Wire recently is that of looking at the written and oral histories of Native land use practices and land uses by non-Native settlers in the 19th and early 20th century. For me, it’s not about replicating the past, so much as understanding how and why Native peoples managed it and how the forests we see today were established.

I recently ran across this interesting piece by a Nyungar man named Glen Kelly in Landscope, a publication of Western Australia Department of Biodiversity, Landscape Conservation and Attractions. I couldn’t find the year it was published. In the paper is this quote from 1830:

While travelling from the Albany District to Perth in November 1830, John Lort Stokes wrote that:

“On our way we met a party of natives engaged in burning the bush, which they do in sections each year. The dexterity with which they manage so proverbially a dangerous agent as fire is indeed astonishing. Those to whom this duty is especially entrusted, and who guide or stop the running flames, are armed with large green boughs, with which, if it moves in a wrong direction, they beat it out … I can conceive no finer subject for a picture than a party of these swarthy beings engaged in kindling, moderating and directing the destructive element, which under their care seems almost to change its nature, acquiring as it were, complete docility, instead of the ungovernable fury we are accustomed to ascribe to it. Dashing through the thick underwood, amidst volumes of smoke-their dark active limbs and excited features burnished by the fierce glow of the fire-they present a spectacle which rarely falls to our lot to behold, and of which it is impossible to convey any adequate idea with words.”

Through the fog of racial bias, you can detect the author’s awe at the native peoples’ fire and land management skills.

But changes in land management have also occurred post-settlement, in fact, somewhat recently.

“that upon the cessation of Nyungar land management practices, dramatic changes occur to the land. Up until 20 or 30 years ago, Nyungar land management practices, which involved frequent cool fires over much of the country, were maintained to a large extent by the cattlemen of the south coast. They used the skills shared with them at the time of settlement, when a major part of the rural work force was Nyungar people. In the last few decades, however, we have witnessed some parts of our coastal land move from productive and vital areas to what we consider sick (mindytch) or dead country (noinch boodja). ”

Again, I don’t know the date of this piece, but Kelly was not finger pointing, but simply calling for:

We believe that the experimental non-use of fire and inappropriate use of fire that has been applied on the southwest coastal lands for the past few decades has been detrimental to the land of our origin. The fault for this does not lie at the feet of any one group or agency, but is a collective responsibility that needs to be recognised and rectified, quickly.

The whole paper is interesting as it places fire in the Nyungar cultural context.

If I had to guess, I would think that in the US, traditional burning knowledge and practices have been passed down in some places and not in others, due to the uprooting of Native people from their land and other factors. It would also be interesting to scan documents and journals from the 17 and 1800s for mention of then-current burning knowledge and practices. I wonder whether anyone has done that?