This was posted as a comment by Richard Halsey of the California Chaparral Institute in previous posts, but it deserves to be on this blog as a guest post…so here it is. -mk

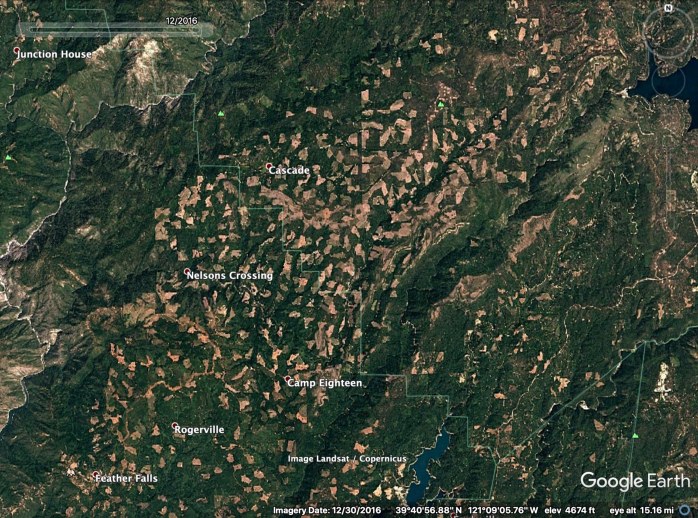

As with the Creek Fire, logging, habitat clearance, and the creation of forest plantations by private corporations and the US Forest Service in the Bear Fire area (in the northern Sierra Nevada) are making the fire worse and threatening lives as a result.

The Bear Fire area has been heavily logged over the past couple of decades – clearcuts, commercial thinning, “salvage” logging of snags, mostly on private lands but also quite a bit on National Forests too.

The consequence?

The Bear Fire dramatically expanded yesterday when it got to this massive area of heavy logging (see image below).

The Bear Fire is now over 200,000 acres (mostly from yesterday), and at least three people have been killed (see perimeter map below). This situation is very much like the Camp Fire in terms of the direct threat of recent logging to lives and homes, by contributing, along with the dominant force of extreme weather and climate change, to very rapid rate of fire spread, giving people little time to evacuate.

None of this is being seriously discussed in the leading media stories on the current fires.

The Main Take Aways

- Logging and forest plantation forestry is a contributor to increased fire spread and fire severity (Zald and Dunn 2018, Bradley et al. 2016 – see below).

- Weather and climate change are the dominant drivers of fire behavior.

- Promoting logging as “fuel reduction” under the guise of fire risk reduction flies in the face of the facts.

The Facts

“Areas intensively managed burned in the highest intensities. Areas protected in national parks and wilderness areas burned in lower intensities. Plantations burn hotter in a fire than native forests do. We know this from numerous studies based on peer-reviewed science.”*– Dominick DellaSala

From: Exploring Solutions to Reduce Risks of Catastrophic Wildfire and Improve Resilience of National Forests. Congressional testimony by Dr. Dominick DellaSala, Sept. 27, 2017.

* The research cited above analyzed 1,500 fires in 11 Western states over four decades – an overwhelming convergence of evidence. Some of those studies include the following:

217 scientists sign letter opposing logging as a response to wildfires (we are signatories).

I’m not a California fire expert, but I do have a couple of questions trying to understand the argument here. First, let’s characterize fire impacts (bad effects on people or ecological things) vs. “more difficult to fight” factors.

I think for this discussion we are talking the MDF? Is that correct? Rate of spread, intensity and what other factors???

1. What part of the Sierra has not been logged? Is the argument that logging in the past 50 years has increased fire MDF? What specifically about those practices and what MDF factor?

2. What about plantations cause increased (risk, intensity, unfightability)? What about plantations.. species? Age? Density? The way they are managed (or not?)

3. Is it that a) fuel treatments (that is reduction of fuels) do not work to change fire behavior as planned and carried out by fuels practitioners; b) they don’t work under certain weather conditions; or c) they make conditions worse.

4. This seems to be about one fire, to what extent are these conclusions about that one fire, and to what extent do you think that they can be applied more broadly? To what kinds of conditions?

Also, I couldn’t get the links to work for the cited papers.

All good questions, Sharon.

The links work now.

Thanks, Richard! If you will clarify the claims you are making (see my previous comment, #s 1 to 4), I’m willing to read those papers and discuss whether we agree that they support your claims.

I do see another possibility. It’s probably coincidence and the researchers have already looked at it and discarded it.

It looks to me, in Figure 1:

https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/documents/strategy/rsc/west/WestRAP_Final20130416.pdf that during the high volume logging years (roughly 1930-1985) the acreage burned is significantly lower than when brakes were applied particularly by the Clinton administration.

Hi Norm:

Regarding your Figure 1 graph:

1. Alaska became a state in 1959.

2. Your “high volume logging years (roughly 1930-1985)” was not during what scientists/researchers are finding may be the worst American West megadrought in 1,500 years, roughly from year 2000 to present. Although what may the worst megadrought in 1,500 years does directly match the increase in the wildfires on the chart you shared. Maybe that was Clinton’s fault.

3. There was a documented wetter and cooler period in the western U.S. from roughly 1950 to 1980.

4. Have you heard of the PDO?

5. Have you seen this U.S. Forest Service chart?

6. Or this U.S. Forest Service chart?

7. Remember the first “National Fire Plan” after those year 2000 fires? This chart was in there.

8. This map may have you seeing red. Red = highest August mean temps on record. Orange in top 10% percentile, going back 125 years.

Cool beans, Matthew. How do I embed graphics in replies?

PDO is the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. We now have my entire knowledge on that.

N

Norm I have a very kludgy way of doing this involving writing a fake blog post and lifting the HTML from it. I am hoping someone will have a better way.

Media Coverage From Axios PM (9/10/20) “The American West is experiencing a mind-bogglingly intense fire season this year, with some areas not expecting relief for months.

• California has now seen the highest number of acres burned in a single season on modern record. The August Complex Fire is now the state’s biggest on record.

• In Colorado, it took a wet September snowstorm to halt the No. 1 and No. 4 biggest wildfires in the state’s history.

• Oregon and Washington are also getting hit hard.

The big picture: A potent mix of climate change and dense forests — the latter partially the product of nearly a century of fire suppression — is resulting in an abundance of drier vegetation that can fuel fires, Axios managing editor Alison Snyder reports.

• The Bear Fire in Northern California grew by an estimated 230,000 acres in just 24 hours this week.

• The Creek Fire, also in California, grew so fast that it required a dramatic helicopter rescue for 142 people.

Between the lines: Fewer forests are naturally reestablishing after fires.

• More dense, dry fuel means more severe fires with trees — and their seeds — burning in their entirety.

• And more land is burning and viable seeds from areas that don’t burn can’t be dispersed far enough to recolonize large areas.

• A recent study of forests in the southern Rockies projects this trend will continue, even under an unlikely scenario where carbon emissions are significantly curbed during the next 20 years.

The bottom line: “The rainy season in California is at least a couple months out, and offshore wind season is just beginning and is early and it could last through November,” says UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain.

• “Things could get worse before they get better, especially in California, Oregon and Washington.”

Hey there folks, long time SW lurker here. I must attest to just being a humble forestry student with some (non-FS, damn that referral process!) field experience. I have worked in the Magalia/Paradise area, I may have even done inventory plots in some of those clearcuts pictured!

I’m just curious about the take away points and how we reconcile them. If we take it that weather and climate change are the two main drivers of fires, and that vegetation management is a minor one, where does that leave us as land managers?

Because if we believe we cannot control large scale, high severity fires, we can expect to see a majority of our forested landscapes transformed by it.

If this is the case, does it not make sense to extract whatever societal value (timber) we can, before fire resets the secessional clock? Or should we take a lighter touch in our management, expecting it to reduce fire severity and achieve lasting effects?

I will say, I write this as a Shasta county resident who has seen the effects of the Carr fire. I have to say, the severity and extent of that fire tell me that letting fires burn uncontrolled in this age of drought and fuel build up seems unproductive for humans and wildlife.

Hi Cameron! I am also a recent forestry student who now works for the FS. Have you looked into the Pathways Program? That is how I was hired; highly recommend! 🙂

Anyway, I work on the Mendocino NF which has largely taken the “lighter tough” approach to forest management you mentioned. There has been very little logging, thinning, or prescribed burning since the mid-1990s. (Check out some cool stats here: https://headwaterseconomics.org/dataviz/national-forests-timber-cut-sold/) That is due to a variety of reasons: lack of capacity/funding, leadership opposition to management in fear of litigation, etc. We have managed to do some smaller fuels treatments, but not on the scale of the fires currently burning.

The August Complex is now up to nearly *500,000* acres. It is the largest wildfire in California history. In 2018, the Ranch Fire burned nearly 300,000 acres of NFS land and was the largest fire of its time. Having a lighter touch on a landscape that historically experienced frequent, LOW intensity fires, hasn’t prevented large, destructive fires from burning. I believe patches of high severity fire are beneficial to landscape heterogeneity but…not at this scale.

Interestingly enough, we have one active commercial thinning project (called “4 Beetles South”) that began in 2018. It is about 50% complete. The intent was to thin across age and size classes to improve stand health (the area is heavily impacted by Dwarf mistletoe and has a past history of beetle kill, hence the name), then follow treatment up with mastication and eventually, prescribed fire. The project area has been encompassed by the August Complex. Initial reports from a coworker who is a Resource Advisor on the fire is that the project area experienced less stand mortality and is in much better shape than surrounding untreated stands.

Making broad statements such as “logging makes a fire worse” start to fall apart when you get out on the ground and look at what is happening at the stand level. We can still provide economic benefits to local communities/small businesses and improve forest health. I do not understand why the two are considered mutually exclusive by many of the folks who post here.

Great comment! I also always look at the bigger picture of how site-specific thinning projects can benefit our forests. The idea that ‘Whatever Happens’ in nature will be fine, unless man intervenes is fundamentally-flawed. With over 85% of all US wildfires being human-caused, how can we have a ‘natural’ landscape? The desire to have a pre-human landscape in the reality of this world is nonsensical. Humans have manipulated California forests ever since the last glaciers receded.

Hi Emily, great to get your perspectice, and what a beautiful area to work! I often feel that broad statements by researchers such as those mentioned in this article really fail to appreciate the perspectives of those who work for months and years on these landscapes.

The Mendocino is indeed is a perfect example of a landscape that has experienced WAY too much high severity fire. And I think we can both agree that we will never be able to stop high severity burns from occurring completely, nor would we want to. But my interest is in maintaining seed sources for conifer species, especially ponderosa pine, in areas that would otherwise type covert when they burn as hot as the Ranch and Carr fires did.

I am very glad to hear that your forest is implementing some good proactive thinning projects. If we can help keep these stands as Refugia and seed sources for conifer species, perhaps they can recolonize burned areas. Otherwise, I feel like us in N.California can look forward to seas of manzanita instead of forests!

I’m keeping my eyes peeled for a pathways internship here in Redding. Keep up the good work!

Thanks Cameron and Emily for a good decision and sharing your perspectives. However, Cameron, where do you get the notion that researchers and scientists actually don’t “work for months and years on these landscapes?” At least that’s what a took from the first part of your comment. The researches and scientists that I know personally who study these issues have spent months, years and even careers plying their trade and expertise on-the-ground in these landscapes. If you think scientists and researchers like Dr. Diana Six, Dr. Dick Hutto, Dr. Cameron Naficy and Dr. Chad Hanson are just desk jockeys staring at a computer screen in an ivory tower, I’d challenge folks to actually keep up them in the woods. I’ve been in these woods with these folks, and they clearly know their way around. Just wanted to point that out. Cheers!

Thanks for the reply, Matthew. I don’t believe any of those you mentioned are desk jockeys (why study forestry if you never get into the woods?! 😉 ) and certainly their work has contributed to the comprehensive body of knowledge us ground-pounders have to work with today.

However, there are plenty of other researchers whose findings contradict those you mentioned. That’s why it’s imperative for practitioners to look at the body of knowledge as a whole.

Dr. Sharon Hood, Dr. Scott Stephens, Dr. Carl Skinner, and Dr. Martin Ritchie are just a few.

Yes, Emily, I get that and agree with you. I personally didn’t get the perspective that you are sharing here from the comment made by Cameron…which is why I responded. Cheers.

Don’t worry, when those names are mentioned along with the Nature Conservancy, they are just pawned off as hacks funded by big timber and industry and the like, and only the researchers mentioned above are worth listening to or right.

Nuance and detail have no place when donations are at stake so you can write off any other opinion as funded by industry.

Is there a particular strategy you are employing here to help resolve the topic of this post?

First, you have not identified anyone who has those kinds of opinions. If you are accusing me, then let’s get something straight. Believe it or not, there are passionate people in the environmental movement who work for nothing, donate all of their time for free, have risked their lives, to fight for what they believe in. Leveling accusations that such people only do such things to increase donations is more about your own perspective on life than others’. For CCI and myself, we have never held back or compromised our principles in the name of donations. If you know different, please enlighten me. Otherwise, be humble and acknowledge your error.

Second, yes, you are right, $ influences how people act and think. $ is definitely the root of all evil, which is why the USFS and the National Park Service were established – to stop the robber barons from destroying our forests. Do environmental groups pander to the Democratic party and do things to ramp up donations? Of course they do.

But, if you have a sincere interest in resolving the issues being discussed, accusing people you don’t know of acting in the interest of $ is going to be a dead end.

My strategy is repeatedly pointing out that you are no better than those you denigrate, and you frequently make claims in the immediate aftermath of a fire with zilch for evidence via actual science to back it up, while in one hand saying “This case A isn’t Case B” while in the next painting a handful of studies as applicable to everything.

Your own response below was:

“I’ve read all of those papers and know many of the scientists involved. I have problems with some of their assumptions, but concur that reducing vegetation can reduce fire severity. There really isn’t any question about that.”

Again, in one breath saying you agree with them, but in the same one writing off everything they have done. You do not do it here, but you and others you associate with, both in blog form and in academic papers, frequently 100% write off anything other highly respected researchers publish.

Further you write:

“But the impacts of logging/habitat clearance on high-severity fire in a forest is really not important here, and is not what I’m discussing in my post. What I am addressing is what role such things have in preventing the loss of life and property in nearby communities, something the USFS continually claims they will do”

But the actual title of this post is:

“Again: Past Logging Makes a Fire Worse, Guest Post from CA Chaparral Institute”

So you say you are not discussing logging, but your own title points towards that being the end all be all, to grab at emotions and cause only more debate and side-taking.

Howdy Matthew, thanks for the reply, I’ve always enjoyed your perspective on this site. My intent was not to denigrate researchers as “desk jockeys,” indeed many of my best mentors and professors have been researchers! My point is that by stating that our fire fighting and forest management actions are completely ineffective, as thousands of firefighters and forestry professionals are in the field working to protect life and property, is ignoring the “ground level” perspective of those who work to implement these tactics. Those folks out there working the fire lines and implementing fuels treatments believe in the difference their actions make, and as Emily stated above, there is plenty of evidence that backs them up as well.

I am curious as to your thoughts on the rest of my comment. If we assume that these tactics are completely ineffective, where does that leave us as forest managers? I don’t believe simply standing back and letting nature take its course is in anyone’s interest, human or otherwise.

Thanks for the support and clarification. FWIW: I am a former wildland firefighter (well, for a season at least). I’ve done fuel reduction work in the woods and around houses. My wife is a former USFS Wilderness Ranger and wildland firefighter. My dad is former volunteer firefighter. I have friends who are volunteer firefighters who are currently fighting the blaze near Detroit, OR. Their crew was unaccounted for a couple of days, but was reached yesterday and they are safe, thankfully. Some of my friend’s places have burned down in the past few days, including places that meant a ton to my family and friends.

In previous years, I’ve dealt with a number of wildfires within 1/2 mile of my house in Missoula, one that was within a few hundred yards and I was the first person on the scene (having to avoid a black bear as I ran across the creek to get to the flames shirtless with a shovel in my hands [my neighbors still tease me about that one!]). I get it. It’s very tough work. It’s very dangerous. They have my respect.

The point I’m trying to make right now (and I believe that Jim Furnish was also trying to make) it that when you have extreme and historic weather events and conditions (which include winds 30 mph to 80 mph, which have been recorded on fires the past couple of days, as well as on some of the larger fires in recent years [I believe one of the big CA fires a few years ago had a recorded 93 mph gust]) there is very little evidence that “fuel reduction” or “thinning” or “logging” works, or has much of any impact. So I do believe we need to be honest and acknowledge that.

Great story about the bear! Must have been quite the scene for the neighbors. My family lost their home from fires this summer, and my thoughts go out to yourself, your family and friends. It’s a been a horrible season for all of us.

I see the points that yourself and Mr. Furnish are making about weather, and I actually agree wholeheartedly. Two years ago, the Carr Fire here in Redding was driven clear across the Sacramento river by winds, something no one expected. My whole family in the Santa Cruz Mountains was very proactively evacuated by Cal Fire this last month, and I think that was due to the fact that the Carr and Camp fire showed us that when the winds pick up, there is no real way to contain a raging fire.

That being said, there are other times when wind is not the overwhelming factor in a fire, fuels are. I believe these cases offer us management opportunities. Further, I feel that there is a lot of public energy behind forest and fuels management after these last few years. I’d love to see that channeled into forest fuels and health projects, rather than just telling folks that we cannot control fires at all.

I’m so sorry for the loss of your family’s home. I can only begin to imagine how heartbreaking that must be.

Cameron, I think you are on to something with your on-the-ground experience. Everyone has biases, and people have a variety of tools to find out about things (controlled experiments, satellite images, modelling, trudging around and observing). I think we’re like the blind men and the elephant. In an ideal world we’d be sharing info and listening to each other, but knowing that we are only touching a part of the unknowable elephant.

It’s hard because at the present time, academic knowledge tends to be privileged over other forms of knowledge and institutions don’t really exist for mutual learning and sharing across disciplines, practitioner to academic, people who live on the land, and so on.

I also think working on a landscape is different from doing a study. I have done both. That is not to denigrate those doing studies, it’s just that there are different kinds of knowing. Here are some things I’ve observed:

1. Being out in all seasons tells you more than one or two seasons.

2. Working with others who have different perspectives (!) on the same stand/area/place.

3. Being in community and talking to folks with memories and observations “I was woodcutting up over the pass last March, and I saw…”

In an ideal world, folks like you would be involved in framing research questions, determining a useful scale to study, choosing disciplines and tools, and reviewing findings. Then we would all together learn so much more. IMHO.

The air quality in San Francisco and Portland is now the worst in the world. Portland’s AQI is 351 this morning. Is little to no management until the big fires come really the way to manage forested and range lands in a time of drought? Is the argument we should accept the loss of life, the long-term health impacts to humans and the damage either long or short-term to our lands and wildlife? Why– to what societal or ecological end? Is that a politically tenable position? I think Cameron has a better perspective. This is a good round-up on fires from the Western Governor’s Association that gives a picture of the scale of fire in the West.

Wildfires continue to scorch the West, leading to at least seven fatalities as of Sept. 10.

In California, where more than 2.5 million acres have burned, nearly 15,000 firefighters are racing to control hundreds of fires across the state, according to CBS News. The SCU Lightning Complex, which has burned more than 396,000 acres, was 95% contained as of Sept. 8, and the LNU Lightning Complex, which has burned more than 375,000 acres, was 91% contained.

The Creek Fire, which erupted Sept. 4, is already the third-largest active incident in the state, burning approximately 175,893 acres – uncontained – as of Sept. 10, reports Eyewitness News. Evacuation orders have been issued for approximately 45,000 residents in Fresno and Madera Counties, and National Guard helicopters were dispatched to rescue dozens of people stranded in China Peak and Lake Edison.

“We talk about grit. We talk about determination. We talk about people that are committed to their job,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said of the rescue operations in a press conference. “That was demonstrated by an act of real courage over the course of the weekend.”

Oregon has been devastated by wildfire as well, with approximately 500 square miles worth of blazes forcing thousands of residents to flee their homes, according to The Oregonian. The fires stretch from Medford to Portland along Interstate 5, which includes many of the state’s major population centers.

Gov. Kate Brown has declared a state of emergency, predicting the Beaver State “will likely experience the greatest loss of property and lives from wildfires in its history.”

Among Oregon’s largest are the Santiam and Lionshead fires, which now cover over 260,000 acres and have all but destroyed Gates, a city of 500 near the border of Marion and Linn Counties. Smaller, but equally devastating fires have ripped through Jackson, Clackamas, Lane, Lincoln, Washington, and Yamhill Counties, as well as the Mount Hood National Forest.

In neighboring Washington, the Cold Springs Fire has burned 163,000 acres, reaching 10% containment as of Sept. 10, Newsweek reports. The Pearl Hill Fire (41% contained) has burned 174,000 acres, the Inchelium Complex Fire (20% contained) has burned 14,756 acres, and the Sumner Grade Fire (20% contained) has burned 800 acres.

The property damage from these fires has been considerable, prompting Gov. Jay Inslee to declare a state of emergency. In Malden, a small town about 35 miles outside of Spokane, approximately 80% of homes and buildings have been destroyed, according to CNN, including the fire station, post office, city hall and library.

Colorado, on the other hand, has seen its luck turn for the better, as cold weather and precipitation – including both snow and rain – aided firefighters this week.

The Cameron Fire, which flared up on Sept. 6, darkening skies in Fort Collins and Denver, was covered with as much as 14 inches of snow on Tuesday (Sept. 8). While the storm did not douse the 102,596-acre blaze – now the fourth largest in state history and only 4% contained – it enabled crews to take a more direct attack in fighting the fire.

Additionally, CPR News reports that the 139,007-acre, largest-in-state-history Pine Gulch Fire near Grand Junction is now 95% contained, and the 32,464-acre Grizzly Creek Fire just outside Glenwood Springs is now 91% contained.

Unseasonably cool and moist weather has lent Montana firefighters a helping hand as well, as crews struggle to control the most dangerous and destructive fires of the season, according to The Great Falls Tribune. As of Sept. 9, the Bridger Foothills Fire still threatens roughly 100 structures in Bozeman, the Bobcat Fire has burned 30,000 acres, destroying at least 10 structures so far, and the State Creek Fire has burned 2,354 acres, destroying two structures and threatening 22 more.

Over the weekend, The RR 316 Fire in Wyoming forced the evacuation of nearby Hanna, Oil City News reports. Residents were able to return Sept. 6 to a mostly intact town, with the exception of a water treatment plant, which was lost to the roughly 15,000-acre, 20% contained blaze.

Earlier this week, a smaller fire forced evacuations along a rural highway in Idaho. According to Idaho News 6, the Bonner County Sheriff’s Office issued the order on Sept. 8, as the fire reached about 700 acres.

Howdy Rebecca. So what is your solution? And can you please share the science or research that would support your proposed solutions in the contact of a “historic wind event,” the worse drought in 1,500 years, established and potential negligence of power companies, the hottest August mean temperatures on record, the hottest annual mean temperatures on records, single-digit humidities, invasive, noxious weeds across the landscape, and humans being responsible for over 87% of ignitions so far in 2020.

I really sense that you feel a need and desire to “do something” but what would that be exactly, and where is the science to back up any notion that it would make any difference what-so-ever in the context of the real world situation, as outlined above? Thanks.

I’m interested in this drought. Where is the drought? Western US? The contiguous 48 aren’t showing one that I can see. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/service/national/timeseries01/110-00/200901-200912-t.gif

https://twitter.com/Timberati/status/823932483422953473/photo/1

Anonymous… Drought is very confusing and I remain confused. However I did read this handy explanation of drought from 2000 and learned… that the concept is complex. check out pages 5-6 for definitions.

This is from page 18

“Do you believe this? Will we be ready if it really does happen? Colorado’s water planners think long and hard about drought. They know it is a part of life in the semiarid west. But most of us never give it a thought. Frankly, we haven’t had to. The last multiyear Colorado drought ended in the late 1970s, and the last severe and widespread yearlong drought Colorado ended in 1981. Yes, there have been local droughts since then, some quite severe, such as the drought southwestern Colorado experienced in 1989-1990 and again from the late summer of 1995 to early 1996.

But droughts of that duration are not uncommon. Overall, since 1982, Colorado has enjoyed the longest spell of wet (compared to historic averages) weather statewide since the favorably cool and wet period from 1905 through 1929 when so much of Colorado was settled and farmed.

For portions of southeastern Colorado, the decade of the 1990s is the wettest decade since weather observations began in the late 19th century.

The heavy precipitation of the 1980s and 1990s does not guarantee that wet weather will continue into the 21st century. Neither does it assure us that drought is imminent. But one way or another, we know that drought will return. The longer we go without drought, the more likely we will be ill-prepared when drought makes its inevitable next visit to Colorado.”

https://ccc.atmos.colostate.edu/pdfs/ahistoryofdrought.pdf

Thank you, Sharon

How

Apologies for being anonymous in this comment. C’est moi.

My 2c worth, after almost 40 years with USFS 1965-2002, and a couple more decades observing since… As any on-the-ground firefighter or fire boss will tell you, when a fire gets ripping with high wind, heat, and low humidity and reaches project size, suppression efforts are band aids, at best. And we are seeing it RIGHT NOW. Control will come with – and ONLY with – a change in the weather. It’s an ugly scene and an ugly truth. But the “wet West” of 1945-1980, coinciding with a huge uptick in logging, population, and residential development, kind of lulled us into a false mindset (of which I was also guilty). Now that drier conditions have become entrenched, exacerbated by climate change, we reap the whirlwind. I approve of veg mgmt to try to reduce fire risk and severity, but have seen my share of fires burn right through treated areas. I strongly endorse focusing on WUI first and investing in fire-wise treatments of forest homes and lots. But when too-close homes start to burn and the domino effect kicks in, best to stand back and take your medicine. Sorry to be such a downer, but all the talk of logging impacts on fire behavior (and there ARE impacts) is akin to arguing about how the clothing I wear affects my weight on the scale vs. weighing naked.

We harvest trees because we need the wood. Pointing fingers at logging isn’t going to solve our fire problem. Just letting things be isn’t going to work either. We are going to have to use all our intelligence and tools that we can muster to face this critical treat to our forests.

What Oregon has lost this week in forest resources, watershed protection, and critical habitat is unprecedented. What Oregonians have experienced in lost of property and smoke filled skies is also unprecedented. It is not time to place blame but to find solutions.

Bob, while blame is often counterproductive, we do need to examine policy and ask if it is effective. With the catastrophic loss of life and property, clearly policy is not effective. That is the policy I highlighted in my post – the myopic focus on habitat clearance and logging as a solution to reducing fire risk to communities. That policy does not work when it matters most – during extreme weather events. Frankly, until we figure out how to protect families and communities, forest management issues need to take a back seat.

This helps explain why the myopic focus on forests is also in error. Most of the loss of life and property in the past 20 years from wildfires have had little to nothing to do with forests. Why the focus on forests? I believe it’s because of the tremendous lobbying effort by the forest/fire management industry and the pandering both parties do to gain their favor. When I am confronted with statements like, “If we’d been clearing the forest, we wouldn’t have fires like this,” after both the non-forested Thomas and Woolsey Fires, there is a problem.

Regardless, you are right. Blame is only going to polarize people. I certainly engage in that because of my frustration. It is something I need to work on.

Richard, I don’t see a myopic focus. I think that’s a straw person. Most of us think that suppression, PB, WFU, community resilience, and fuel treatments all have a role to play.

So no one is saying that mechanical fuel treatments are the only thing to do.

There are plenty of fires that aren’t extreme. Your judgment is that (mechanical fuel treatments) don’t work during extreme weather events, that is when it matters most. I suppose you could argue that about any problem, why protect from floods, earthquakes, etc. if the intervention wouldn’t work when the “big one” hits. I’m happy with increasing opportunities for suppression folks in average everyday fires. That’s a choice, and not an error IMHO.

Also, living near three fire areas, I’d say the fact that “most loss of life and property” may be true nationally, it’s certainly not true in my area and possibly state. As I’ve said many times, choosing a scale to look at a problem is important. When I lived in S Cal, I wasn’t worried about about forest fires. When I lived in Pollock Pines, I pretty much was. Sure, there are more media and people in the non-forested urban areas of California, but I think voices from forested areas also count.

I do agree that certain citizens very loudly proclaim their lunacy and ignorance regarding California wildfires. It’s kinda fun to confront people on Facebook who, for example, blame Governor Newsome and environmentalists for the current forest fires. I fully expect QAnon to incorporate these fires into their suite of conspiracy theories. There are ridiculous reports that ANTIFA was responsible for the fires in Oregon and Washington. The craziest one involves “Directed Energy Weapons”.

Really, I think forest policy in Sierra Nevada National Forests is sound. It’s not perfect but, the work that gets done is usually good for the land, IMHO. It has the right balance, for today’s social order.

There is little that could of stopped these fires with the weather conditions we had. The only hope we had was that the fires wouldn’t start. Seems like maybe some humans caused that. It is still hard to believe how far and fast the fires traveled.

I think it would be good idea if all fires were put out as fast as possible in Oregon between June 15th and October 1st. If you are a believer in fire is necessary don’t do it during the dry hot months of summer. I have seen to many let it burn fires escape with catastrophic results.

We need to log because we need the resource. It should be an on going discussion on best practices over the entire landscape. It is not a resource to be wasted.

Richard, I appreciate your heartfelt concern.

It is very smokey in Oregon.

Here’s the thing about Western science: the results of any one study are not static, and they are meant to be tested over and over and over. If you pick a small handful of studies from the larger scientific body of knowledge we have accumulated over the years, of course it will be easy to boil down to “logging bad! No logging!” or “logging good! Log ALL the forests!”

To prove my point, here are a handful of studies that suggest thinning, logging, or other types of fuel treatments effectively prevent high severity fires:

Safford, H.D. et al. 2009. Effects of fuel treatments* on fire severity in an area of wildland–urban interface, Angora Fire, Lake Tahoe Basin, California.

“Our results show that fuel treatments generally performed as designed and substantially changed fire behavior and subsequent fire effects to forest vegetation. Exceptions include two treatment units where slope steepness led to lower levels of fuels removal due to local standards for erosion prevention. Hand-piled fuels in one of these two units had also not yet been burned. Excepting these units, bole char height and fire effects to the forest canopy (measured by crown scorching and torching) were significantly lower, and tree survival significantly higher, within sampled treatments than outside them.”

*These treatments included the commercial harvest of trees up to 29”.

Ritchie, M. et al. 2006. Probability of tree survival after wildfire in an interior pine forest of northern California: Effects of thinning and prescribed fire.

“The model shows that probability of survival was greatest in those areas that had both thinning and prescribed fire prior to the wildfire event. Survival was near zero for the untreated areas. Survival in thinned-only areas was greater than untreated areas but substantially less than the areas with both treatments.”

Schmidt, D.A. et al. 2008. The influence of fuels treatment and landscape arrangement on simulated fire behavior, Southern Cascade range, California.

“Treatments included thinning by prescribed burning (burn-only), mechanical thinning (mechanical-only), mechanical thinning followed by burning (mechanical-burn), and no treatment (control). At the stand level, the mechanical-burn treatment most effectively reduced both surface fire (e.g., decreased flame length) and crown fire behavior (e.g., torching index). At the landscape level, treatment type, amount, and arrangement had important effects on both fire spread and fire intensity.”

Hood, S. et al. 2016. Fortifying the forest: thinning and burning increase resistance to a bark beetle outbreak and promote forest resilience.

“Our results show treatments designed to increase resistance to high‐severity fire in ponderosa pine‐dominated forests in the Northern Rockies can also increase resistance to MPB, even during an outbreak. This study suggests that fuel and restoration treatments in fire‐dependent ponderosa pine forests that reduce tree density increase ecosystem resilience in the short term, while the reintroduction of fire is important for long‐term resilience.”

Stephens, S.L and Moghaddas, J.J. 2005. Experimental fuel treatment impacts on forest structure, potential fire behavior, and predicted tree mortality in a California mixed conifer forest.

“Thinning and mastication each reduced crown bulk density by approximately 19% in mechanical only and mechanical plus fire treatments. Prescribed burning significantly reduced the total combined fuel load of litter, duff, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 h fuels by as much as 90%. This reduction significantly altered modeled fire behavior in both mechanical plus fire and fire only treatments in terms of fireline intensity and predicted mortality. The prescribed fire only and mechanical followed by prescribed fire treatments resulted in the lowest average fireline intensities, rate of spread, and predicted mortality. The control treatment resulted in the most severe modeled fire behavior and tree mortality.”

What is actually happening on the ground is so much more nuanced. And extrapolating results from a small portion of the scientific body of knowledge to fit a narrative is the first thing I was taught NOT to do during my time as a graduate student at Yale.

Emily, thank you for offering up some contrary research. I’ve read all of those papers and know many of the scientists involved. I have problems with some of their assumptions, but concur that reducing vegetation can reduce fire severity. There really isn’t any question about that.

But the impacts of logging/habitat clearance on high-severity fire in a forest is really not important here, and is not what I’m discussing in my post. What I am addressing is what role such things have in preventing the loss of life and property in nearby communities, something the USFS continually claims they will do. The evidence has been clearly presented in the recent fires that they are wrong – fuels treatments typically fail when it matters most – during extreme wind-driven fires.

Take a look and the aerials of of the town of Talent, or any community impacted by a wind-driven fire. You know this of course, but the communities are burning because they themselves are flammable. We can fix that. People are dying trying to evacuate. We can fix that. Homes are being placed in highly flammable environments. We can fix that. Forests? That’s a different issue.

I am sure you’ve read Jack Cohen’s research.

But when all the air in the room is being consumed by talk about thinning/logging forests, and only a few shouted-down voices are asking for everyone to just look for a moment at why we are losing so many loved ones in wildfires, we just keep going down the road we always have.

To use your words, here’s the thing about research – it fails to convince anyone who already has their mind made up. This applies to everyone, not just to me as you seem to be suggesting at the end of your post. In fact, the more facts you throw at someone to support your position, the more entrenched the other person becomes. That’s why most of the discussions here end up nowhere.

So let’s forget forestry for a moment, and all the papers, and discuss what we can focus on to find common ground – the value of life and communities. It’s likely someone will say that the surrounding environment and community safety are related. Of course they are. But focusing on the surrounding environment almost exclusively, something that honestly is not something we can really control, prevents us from finding solutions.

Also, for what it’s worth, the Bear Fire did not “expand dramatically” when it reached the logged areas northeast of Lake Oroville. See the progression map here: https://ftp.nifc.gov/public/incident_specific_data/calif_n/!2020_FEDERAL_Incidents/CA-PNF-001308_PNF_North_Complex/GIS/Products/20200911/prog_arch_e_land_20200911_0241_North%20Complex_CA-PNF001308_09011day.pdf

The logged portion is on the back end of the unstoppable 180,000 acre run that fire made between 9/8 and 9/9 due to extreme winds and heat. Whether it was heavily logged or an untouched wilderness, that area would have still been torched and would have continued to carry the rapidly-spreading fire.

Thank you for pointing that out. Nuance and detail have never been a strong point of CCI or JMP, and this current argument they are presenting with *zero* evidence and only hand picked images and statements to pull at emotions is of not only no help, but harmful to the overall discussion really.

As I pointed out earlier, ad hominem attacks not only weaken your argument, but prevent the kinds of discussion needed to find common ground.

I would also expect that the canyon where the Feather River’s middle fork goes acted as a ‘conduit’ for fire, aligned perfectly with the northeasterly wind direction. We’ve seen this situation on several recent Sierra Nevada firestorms. Both the Rim and King Fires burned quickly through the less-managed river canyons. I saw very little management in that canyon on the Plumas.

Emily, I don’t know if you were on the fire September 9. If you were, it would be helpful if you could provide insight into what happened. I wasn’t, so all I can go by is the progression map and what I know happened during fires when they hit non-forested areas – they make incredible runs.

All the map shows us is that the big push was accomplished in one day. It does not have an hour by hour spread rate. Without it, the conclusion you are making is not supported by the available data, nor is your statement that there would have been no difference in fire spread between untouched wilderness or a heavily logged one.

I’ve changed the map in our post to show exactly where the clearcut areas are in relation to the spread on September 9. Your characterization of the location is not accurate.

https://californiachaparralblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/10/again-past-logging-makes-a-fire-worse/

You also seem confused about the color coding of the fire progression map. The big day was Sept. 9, with over 180,000 acres. If you look at the areas that the fire spread through on that day on Google Earth (using the history option), you will see a huge landscape of private timberlands and national forest lands that have been heavily subjected to a combination of clearcutting, salvage logging and commercial thinning over the past two decades.

Weather and climate are always the dominant factors, of course, but logging is a major additional contributor to increased fire intensity, as found in Bradley et al. (2016). From my study of the Camp Fire, the fire spread through cleared/logged areas occurs at a rate that is very rarely seen in a forest fire.

The Bradley paper can be found on our website here:

https://californiachaparral.org/forest-fires/

Emily & Others of like mind commenting above.

The content relayed in this post is just another example of faux science consisting of cherry picking an example that, on the surface, appears to support a certain point of view. After finding such an “observation” the faux scientists and their rabid supporters put horse blinders on so that they won’t see any contradictory evidence. Said coalitions supporting examples that contradict fundamental, long established and broadly validated science are not interested in investigating to see if there are any causal variables beyond their favorite whipping boy. They either deliberately ignore or are ignorant of statistically sound research principles/processes that are required to come to such conclusions.

Many of us have spent years on this site explaining the sciences and the statistically confounding variables that could have invalidated their conclusions. We have wasted our time supplying countless references that contradict their opinions. We explained countless other variables that could explain the real reason for the variance thereby discovering the real reason for the “observation”. And could lead to a conclusion which conforms to well validated established science rather than the mere opinion of someone with a policy agenda, a sleeping mask over their eyes and an index finger in each ear.

You have been trained in and understand the relevant fundamental sciences necessary to discern between truth and falsehood. Use that knowledge and stay current in the scientific literature. You are a member of a wonderfully exciting and constantly improving profession. Listen to the misguided, consider their offerings, learn from and be affirmed by the discussions here and elsewhere. Don’t let the angry ones get you down. Fight the good fight as many before you have and you will be glad that you had such a fantastic life as a well rounded, well trained professional serving in the broadest, most well rounded environmental profession that there is.

Hi Gil, thank you for your insight here and elsewhere on the sight. Everyone has their biases, I know I do! The one thing I have heard from folks in our profession, again and again, is that broad directives over large areas only end up constraining land managers who want to improve their work areas. This was what I was getting at with my comment about “on the ground perspective” being overlooked. Broad studies can tell us quite a bit about the generals and even minutia of a forest, but it often takes the trained eye of individuals who have spent years working in the same area to pick up on what their forest needs. I’m not saying that they should rely solely on their own observations, but they shouldn’t always be overruled by broad statements such as the ones in the original post.

I already know from my limited experience that it’s not a great idea to tell any forester that you know his or her woods better than they do, no matter what you might have read or seen. All perspectives are important here.

Gil, instead of engaging in an us vs. them cheering session, let’s discuss the actual points in the post. Yes, there’s a lot of emotion here, but if you want to reach common ground, patience and avoiding personal attacks are essential.

In all of the posts I have offered here, I have never questioned your values, your truthfulness, or said things about you that I have no way of knowing. Not in my most delusional condition would I call you a faux scientist, a rabid follower, or demean your profession as you are doing with me. While you didn’t name me personally, the insults you are leveling are pretty clearly directed at me.

Your experience is valuable and you clearly have an expertise in the field of forestry. That is where you shine. Saying lousy things about others distracts from that.

While we seem to be in an environment these days where personal attacks appear to be an acceptable response, engaging in them only makes the attacker feel good (in the short term). They do nothing to make the world a better place.

FYI: I gotten a number of emails in the past few hours from Richard Halsey at the California Chaparral Institute. He only sees 13 comments posted on this blog post, despite the fact that there are currently 23 comments posted here (and mine will be #24). Richard has restarted, refreshed, changed browsers and tried just about everything to see all the comments posted here, but with no luck. This seems to happen on this blog from time to time and I have no idea what the problem is, or what to do about it. I just wanted to let people know, especially if Richard is not responding to comments he actually cannot see or read.

Hi Matthew, I had the same issue there for a bit seeing comments, but they did eventually show up for me after enoug refreshes. Maybe they are waiting to get through the moderation process?

As a moderator, I haven’t seen any backlog of comments awaiting approval. Sometimes WordPress has issues, and sometimes user computers are affected. If I see any offending comments, I don’t approve them, or delete them. I leave that to someone else. I’m sure that the other moderators are the same way, regardless of how they lean.

“As a moderator, I haven’t seen any backlog of comments awaiting approval.”

Nor have I.

Hi Cameron, Thanks for helping us figure this out and sharing what you are seeing, or not seeing. However, I’m also a longtime moderator on this site and approve many comments, pretty much daily. The issue that Richard is experiencing (and that other people have written to me about over the past few years [a big discussion on the Bitterroot National Forest, rock climbing and mountain biking comes to mind]) is the fact that some people cannot see comments that have already been moderated and approved and are clearly visible for other people. Despite re-starting, re-freshing, and switching browers they just can’t see to see all the comments.

Hey folks, I see what you’re saying now, I started with Safari on my phone and am now on Chrome, and I can finally see most of the comments. It does seem to change considerably based on what device you use and when you look at the page.

Never have had a problem with FireFox.

I don’t think it’s moderation, as Matthew is usually right on that and I can see any waiting and approve them right away. If Matthew and I can count 24 or 25 or whatever, everyone should be able to. Puzzling. Cameron, what devices are you using and have you tried different browsers?

Thanks Matt for pointing this out. The comments stayed at 13 all day yesterday until I stopped looking. They appeared this AM.

Folks, I think it is fair to say all of us likely love what we do, enjoy the natural environment, and have a wealth of experience to share.

Unfortunately, the amount of personal vitriol that I find here is making this place unhealthy for me. I know there are a few who are able to share their disagreements without leveling personal attacks, but the handful that can’t seem to do so make it impossible to get through a few posts without feeling demeaned. If the intent was to make me feel sad, it has been accomplished.

Fight, fight, fight is in our genes. It kept us in the clan so we wouldn’t get tossed out. But honestly, it will likely be the end of us.

Stay safe.

This is my last post here.

Richard, thanks for this observation. Perhaps we have sadly gotten used to the “personal attacks” and read right past them. I didn’t notice anything unusually bad.

And I personally think that fighting is more in the hormones of a certain gender than in our DNA, but that’s just me. I’m sorry for any hurt you experienced, and appreciate your contributions.