There’s an interagency effort to deal with increased recreation in northern Colorado called NoCoPlaces 2050. Here’s a link. They have a research page that looks interesting, including behavioral science.

This is from an article from the Vail Daily News.

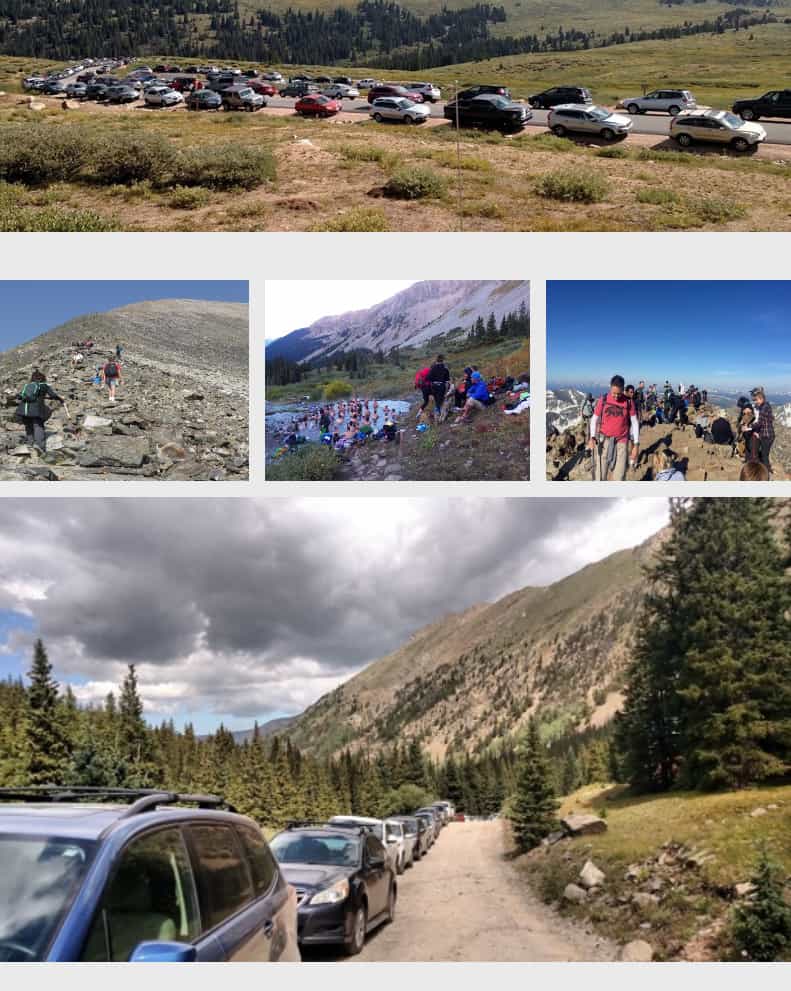

Consultant Steve Coffin said virtually every place within a six-hour drive of the Denver area is seeing increased pressure on public lands.

Coffin is one of the coordinators of a group called NoCo 2050 places. That group has brought together public land managers, local government representatives and others to look into possible strategies to address the growth in public land use.

Most of that pressure is coming from the Front Range. Coffin said that 94% of the state’s population growth in the past decade has been concentrated on the Front Range. That’s why the mountains on the east side of the Continental Divide have seen so much pressure on public lands.

The idea behind NoCo 2050 Places is, in part, to encourage greater cooperation between agencies and take a broader view of how to manage the pressure on the state’s special places.

Langmaid attended — virtually, of course — a meeting of civic leaders, an offshoot of the NoCo 2050 Places project.

Langmaid said the ideas discussed by that group include both a broad vision and talk about the future.

“What I told the group is that this is not in the future, it’s right now, and were behind the curve,” Langmaid said.

Part of the problem is that public land agency budgets continue to dwindle, especially as more of those agencies’ funds end up committed to fighting wildfires.

What that means is that towns depending on tourism will have to spend more of their money on public private partnerships with government agencies.

In addition to increased pressure on local government budgets, Langmaid said there are other potential problems.

“If you start restricting access, do you create inequities?” Langmaid asked. Those inequities could include blocking access to those who don’t have the access or skills to make on-line reservations. If fees are charged, is that a barrier to lower-income users?

“These are big questions,” Langmaid said.

No silver bullets

No one has yet come up with solid answers to these and other questions.In addition, Langmaid said it’s time to rethink destination marketing.

“We need to be looking at destination management with as much fervor as destination marketing,” she said. Successful marketing doesn’t mean communities — or public lands — are ready for the impact visitors bring.

Vail has already funded cooperative projects with the Forest Service including the Front Country Ranger program. The town is also working with the Forest Service and Colorado Parks and Wildlife on a “landscape level” project to improve wildlife habitat and lower fire danger on more than 4,000 acres on the north side of Interstate 70 starting at the town shops and East Vail.

“We’re the ones creating the problem; we have a responsibility to (help address it),” Langmaid said.

While any system to restrict trails into public lands will take time, Stockmar said perhaps the town could take some action on its own.

“We do have authority over (trail) access points,” Stockmar said. “We have the very thin potential leverage that (users) are on town land.”

Whatever solutions come to pass, Langmaid said it’s important for the town and users to maintain “a very high quality experience with wilderness values” on those well-used trails.

Themes in the Vail Daily story that we’ve mentioned before:

* Education not necessarily working without enforcement.

* Reducing numbers and/or improving behavior.

* Adjacent communities possibly restricting public access.

Meanwhile, the human population continues to grow.

My very first thought was that while everyone has been caught off guard by this years hoards of new public land visitors, I’ve always thought the Forest Service has had inadequate recreation planning. Over the past 50 years there has been an escalating increase on planning new Wilderness areas and formulating various restrictive policies, combined with a somewhat corresponding disengagement of recreational understanding that puts Forest’s behind the curve rather than in front making proactive decisions.

One example that I can relay is that in the Northern Region, Wilderness management and recreation are typically a combined position. Recreation has taken a backseat to Wilderness maintenance and planning at almost every planning effort that I’m aware of. Twenty years ago the Wilderness officer wrote the second study for the Hyalite Porcupine Buffalo Horn Wilderness Study Area. The entire evaluation of bicycles in that study was an illl-worded remark that the activity was “exploding” in the area. It was written as if the author had been under a rock for the previous 20 years and was suddenly caught by surprise.

Same thing in Colorado. They are caught by surprise. I bet they’ve been focused on Wilderness evaluation, deskbound with NEPA paperwork, and no one was addressing recreation infrastructure proactively. Pending legislation, “Recreation not red tape” would help this imbalance as it would create focus on recreation evaluation that should equal wilderness evaluation.