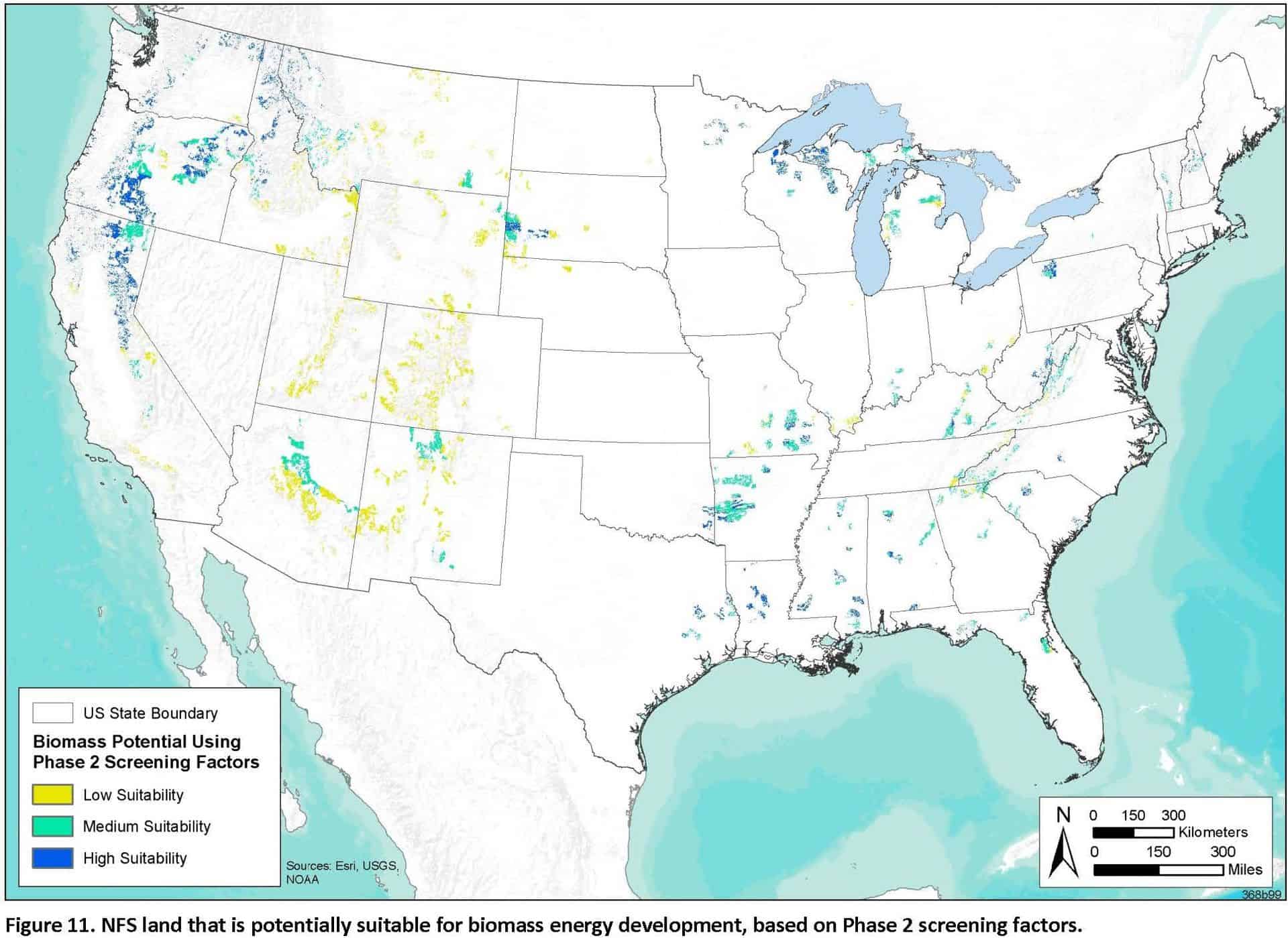

From the 2013 Argonne National Lab study

From the 2013 Argonne National Lab study

Apologies to everyone and especially Mac.. I couldn’t get the links and image to work on some platforms for this so am trying various tricks, like reposting the whole thing. Thanks to folks helping me troubleshoot the problem! Please comment below if you can’t see the one link to the Argonne report nor the chart.

Here’s Mac McConnell’s idea for the new Administration:

MANAGING NATIONAL FORESTS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION

In 2011 the United States Forest Service (USFS) promulgated a program document entitled Strategic Energy Framework.

“The Forest Service Strategic Energy Framework sets direction and proactive goals for the Agency to significantly and sustainably contribute toward resolving U.S. energy resource challenges, by fostering sustainable management and use of forest and grassland energy resources.”

I write this paper in hopes of furthering these goals, focusing on the national forests’ signature resource: biomass.

Biomass

In 2013, the Argonne National Laboratory, under contract with the USFS, published a report “Analysis of Renewable Energy Potential on U.S. National Forest Land”. It revealed that, at that time, some 14 million acres of national forest (NF) land were highly suitable for biomass production. This resource is renewable, immense, and virtually untapped.

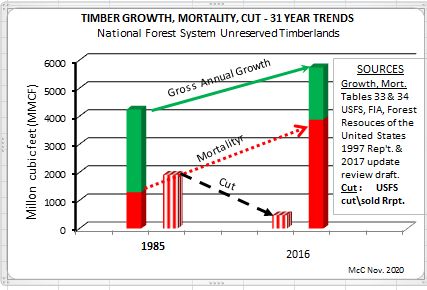

Should this resource be developed? The question has been raised as to whether the national forests can support a larger timber harvest. Alternatively, should the carbon remain sequestered in standing trees , thus slowing the progression of climate change? The answers can be found in the chart.

During the 31 years period ending in 2016, drastic changes took place in the management of national forest resources. Emphasis (dollars|) shifted from tangibles, such as timber, forage, and road construction and maintenance to intangibles (wilderness experience, endangered species and old growth protection) and fire management.

As a result of these factors, plus chronic under-funding, serial litigation, and over-planning and analysis, timber harvest has declined by 75% and the forests are now harvesting about 8% of their growth. Mortality due to fire, insects, and disease increased by 200%.. Net annual growth (Gross annual growth minus Mortality) decreased by 39%.

The chart makes apparent the long-term adverse impacts of virtual non-management. As trees in unmanaged forests and under stress from climate changes die in increasing numbers they no longer sequester carbon, but rather become sources of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane. Prudent harvesting for energy biomass uses these dead and dying and unwanted trees to replace fossil fuels while creating a healthier and more resilient timber stand. It also creates a market for presently unmerchantable material and a new job market in rural areas urgently needing economic help.

Other renewable resources

While this paper focuses on biomass, the 2013 Argonne Lab report also investigated the presence of the solar and wind energy potential on NF land.

National forest solar resources are abundant with 565,000 acres of NF land with a production capacity of 56,000 Megawatts potentially available, primarily in the Southwest.

While minor wind opportunities exist locally, the principle developable areas are located on the 17 national grasslands totally 4 million acres.

Proposed Action

I propose that the Forest Service initiate a greatly expanded program of biomass utilization focused on active participation in the development of small-scale (< 20 MW) energy projects on selected national forests. This would include assistance in siting (providing suitable land for facilities), planning, financing (grants or low-interest loans), and long-term contracts that would ensure a continuous fuel supply.

Congressional authorization and funding will allow this action to take place.

Bibliography

USDA Forest Service 1997, FIA Forest Resources of the United States, 1997 (Tables 33 & 34)

USDA Forest Service 2011, Strategic Energy Framework

USDA Forest Service 2017, FIA, Forest Resources of the United States, 2017 (Tables 33 & 34)

USDA Forest Service, Annual Cut and Sold Report

McConnell, W.V. (Mac). 2018. Integrated Renewable Energy from National Forests in193 Million Acres, 32 Essays on the Future of the Agency, Steve Wilent editor, Society of American Foresters,651:333-338

Zvolanek, E.; Kuiper, J.; Carr, A. & Hlava, K. Analysis of Renewable Energy Potential on U. S. National Forest Lands, report, December 13, 2013; Argonne, Illinois..

W.V. (Mac) McConnell is a self-styled visionary who, b(uilding on his 30 year career with the U,S. Forest Service and mellowed by 47 post retirement years in the real world, hopes to change the way the Service manages the peoples’ forests. He specializes in energy biomass management (short-rotation-intensive culture energy crop systems)

*Additional Note from Sharon: The Argonne study also looked at hydropower and geothermal; it’s interesting to look at the tables by forest and also the maps for concentrated solar, PV, wind, hydro and geothermal. The biomass estimates focused on logging residues and thinning. Criteria are listed on page 12 of the report.*

Why does this keep getting posted here?

There is no scientific evidence to support the burning of biomass/forest debris/trees in the place of fossil fuels as being climate friendly.

https://johnmuirproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/200TopClimateScientistCongressProtectForestsForClimateChange13May20.pdf

It keeps getting posted here because many scientists feel that there is evidence that does support it.

Don’t you think it would depend on a variety of assumptions about where you get the trees, what other uses if any they would be put to, what exactly they are substituting for (co-generation) and so on?

If Jane has thinned her property and burns wood in her woodstove and uses less propane, it’s hard for me to believe that “scientific evidence” shows that this is not climate friendly. Of course, this is not what they are talking about, which raises the question “what specifically ARE they talking about?” Not clear from the letter.

Gary, that is untrue. The efficacy of forest biomass as a climate-positive substitute for fossil fuels depends completely on what system is being studied (i.e. harvesting an entire stand/forest for biomass vs. using only logging slash) and how long the carbon effects are monitored (there is a marked increase in CO2 in the short-term when using biomass, which is usually offset as a stand begins to sequester more carbon again). There are plenty of studies that demonstrate biomass is an effective substitute, once certain stipulations are met.

Gustavsson et al. 2015: “The results show largest primary energy and climate benefits when forest residues are collected and used efficiently for energy services. Using biomass to substitute fossil coal provides greater climate change mitigation benefits than substituting oil or fossil gas. Some bioenergy substitutions result in positive CRF, i.e. increased global warming, during an initial period. This occurs for relatively inefficient bioenergy conversion pathways to substitute less carbon intensive fossil fuels, e.g. biomotor fuel used to replace diesel.”

McKechnie et al. 2010: “For all cases, harvest-related forest carbon reductions and associated GHG emissions initially exceed avoided fossil fuel-related emissions, temporarily increasing overall emissions. In the long term, electricity generation from pellets reduces overall emissions relative to coal, although forest carbon losses delay net GHG mitigation by 16−38 years, depending on biomass source (harvest residues/standing trees).”

What am I curious about is the utilization of dead trees as biomass. Over 400,000 acres of the forest I work on have experienced high severity (stand replacing) fire in the last two years. That’s *a lot* of fuel to deal with, and we will address maybe 0.5% of it through salvage logging. We can’t even pay to have it taken off our hands because we are outside the “economic bubble” of one of the only biomass facilities in northern California. I would like to see more research into the viability of dead trees as biomass. Seems like there is a dearth of it.

In my experience, biomass material is usually a ‘side-effect’ of “thinning from below”. When whole trees are skidded and de-limbed at the landing, you end up with a mountain of logging slash. It is too expensive to transport it to a biomass plant, due to the distances. One idea could be to transport the slash to a ‘regional collection site’, which would be at strategic places, throughout the Sierra Nevada, have connections to the grid, and have ample room to store relatively large amounts of biomass. A mobile biomass burner could relocate to multiple sites to process the biomass into electricity on days where it won’t impact air quality, too much.

I have worked on Service Contracts, where sub-merchantable trees were thinned, and the Contractor was free to profit from selling any product he could make and sell. Those projects worked out extremely well, including a perfect under-burn.

Emily, thanks for the cites. I think there has been quite a bit of research on different uses of dead trees. We’ll spend some time looking at these and different ideas about why they have not been successful so far (and new efforts to fix that).

I’ve been working on an article about the Forest-Climate Working Group’s policy platform for the 117th Congress. It’s worth a look — and worth supporting. This applies to all forests — public and private.

https://forestclimateworkinggroup.org/resource/forest-climate-working-group-policy-platform-for-116th-congress/

The group includes 58 members, including forest products companies Weyerhaeuser, Hancock Natural Resource Group and others), associations (such as my employer, the Society of American Foresters, and the National Association of State Foresters), conservation organizations (the Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy), forest carbon project managers (Finite Carbon, the Climate Trust), and other organizations. Recreational Equipment Inc. (REI), the outdoor gear and clothing retailer, is a member.

The FCWG is guided by four key principles:

1. Climate change is real, and forests must be part of our nation’s response.

2. Keeping forests as forests is the foundation to all forest-climate solutions.

3. Forests can do even more to slow climate change if we provide the right science and financial incentives to help private forest owners and public land managers plant and re-plant forests, and manage with an eye to carbon.

4. Protecting forests from climate change is equally as important as trapping more carbon in forests. Many forest resources could be lost to the stresses of climate change, and cutting edge-science has showed that US forests will lose their capacity to store carbon, and release lots of carbon already stored, if we don’t help forests adapt.

I can accept the idea that burning dead trees or slash for energy could reduce fossil carbon release, and using them in lieu of live trees for wood products would promote carbon sequestration. There are ecological costs that would need to be considered, but the climate tradeoff may be worth it in some circumstances. But using live trees raises a lot more questions and would change the calculation substantially.

Biomass energy is a source of net emissions, not net sequestration.

DellaSala, D.A., and M. Koopman. 2015. Thinning combined with biomass energy production may increase, rather than reduce, greenhouse gas emissions. Geos Institute, Ashland, OR. http://www.energyjustice.net/files/biomass/library/biomass_thinning_study.pdf

There are a host of other problems with biomass energy:

• Economies-of-scale conflict with sustainability. Centralization is better for the market, but the restoration needs of the forest are geographically dispersed. Concentrating biomass extraction around a central point may compromise ecological goals.

• Restoring ecological processes, including natural mortality and dead wood habitat, is important and requires retention, not removal of biomass material.

• Mechanical fuel reduction must be strategic, and focus on the “structure ignition zone” near communities; there is no need to treat every acre.

• The long-term supply of small trees is not sustainable. After a period of fire exclusion and ingrowth of small trees, the first fuel reduction entry may be economically attractive, but the next entry should be with fire, not heavy equipment.

• Electricity is a relatively low value use of wood. There are already a well-developed markets for wood products and wood waste. Bio-energy may not be the highest and best use of wood.

• To make ends meet, biomass efforts must often be coupled with other economic activities (e.g. logging, roads, fire suppression) which may be counter to restoration objectives.

• Competing renewable energy sources such as wind are cheaper than forest biomass.

• High transportation costs do not bode well for such a remote and dispersed raw material supply.

• Power infrastructure limitations: Connecting biomass plants to the grid and wheeling power from where it’s generated to population centers are difficult, due to institutional inertia and bottlenecks in the power grid.

• Cellulosic ethanol is still a pipe dream. The “magic bullet” enzymes may never be found. Genetic engineering may be required to make weaker plant fibers, but it is unwise to genetically pollute our forests which we expect to grow strong, tall trees that will make long-lasting habitat and strong lumber.

• Many forest roads are on steep terrain and unsuitable for chip trucks.

• After logging to remove merchantable trees, a second entry to remove unmerchantable biomass may have unacceptable cumulative impacts on soil, water, wildlife, & weeds.

• We need humility. Due to climate change we may have limited control over fire, fuels, and forest succession.

Second, is your quote from DellaSalla and Koopman? Some of those claims are worth discussing.