Both of these sources (Limerick’s history post and the webinar) talk about people in the middle.

The Colorado Media Project had an interesting webinar on “Reclaiming the Public Square: Trust, Media and Democracy in Post-Election Colorado.” I think it’s worth watching to get the views of (some) media folks on problems and solutions. The presentation by Stephen Hawkins runs from 5:06 to 18:00 and was my first introduction to More in Common

More in Common works on both short and longer term initiatives to address the underlying drivers of fracturing and polarization, and build more united, resilient and inclusive societies.

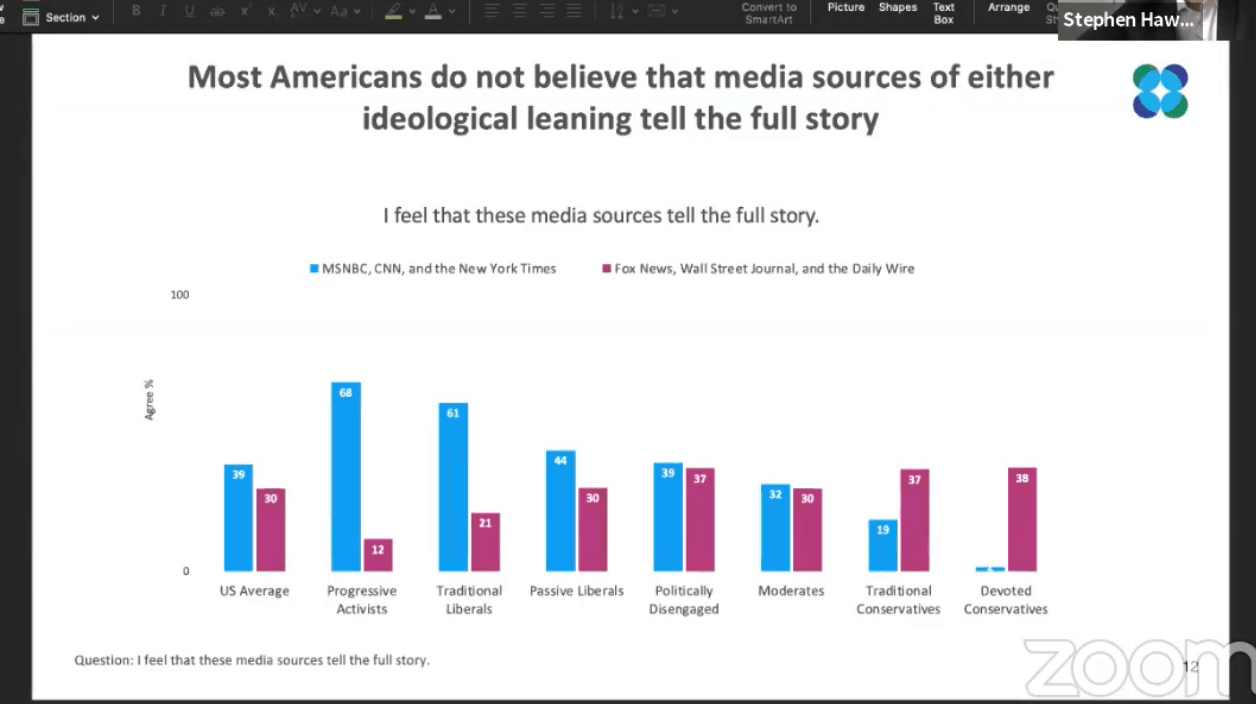

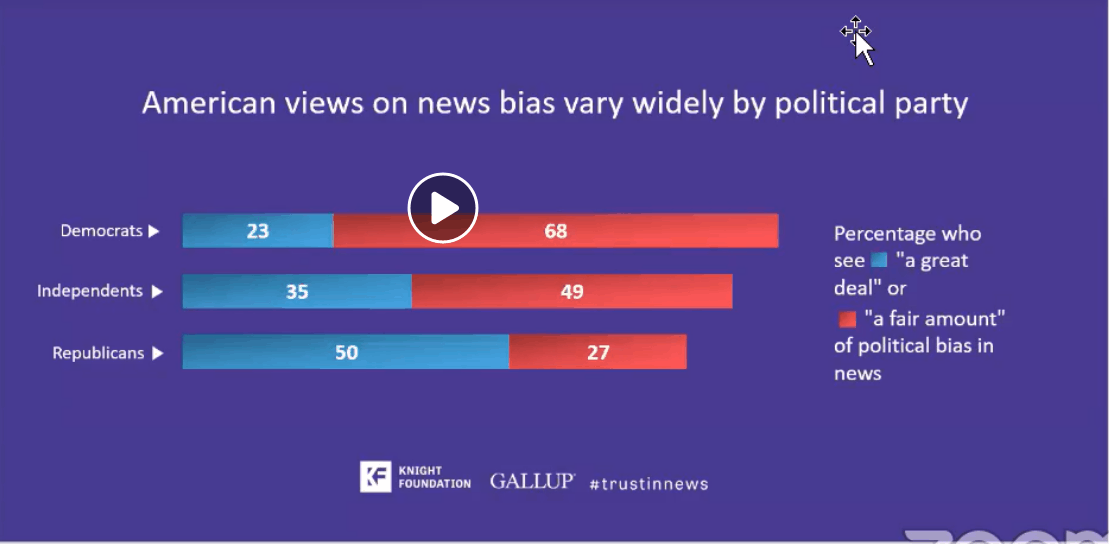

More in Common divides Americans politically into eight “Tribes” (see the chart above). Following that is a presentation about some Gallup polling that put people into three political categories (Ds, Is and R’s)(see chart above). It would be interesting to take some forest-related questions and see what different narratives might result from dividing folks who answer into three or eight categories. My guess is that eight would yield more understanding of peoples’ points of view. You don’t have to be a sociologist of science to think that how you structure the study (what groups you choose, exactly what questions you ask) can affect the answers you obtain.

Patty Limerick had an interesting idea in her “Not My First Rodeo” post History’s Essential Workers about the role of interpreters in Western history.

A Familiar Story from the Past, A Fresh Approach for the Present

As Meriwether Lewis and William Clark traveled from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean, the terrain they crossed presented an almost unfathomable variety of landforms. And yet the diversity of the languages they encountered proved far more difficult to comprehend.At every stage of the trip, the expedition encountered a group that spoke a different language. On a few occasions, this required Clark and Lewis to engage in an early nineteenth century experimentation with what would later be called “the telephone game,” a chain of interpreters lined up to pass on a single message. In one episode when clear communication was of great importance, Lewis spoke in English to a French soldier from the expedition. The soldier then spoke in French to the expedition’s official interpreter, Toussaint Charbonneau. Charbonneau then spoke in Hidatsa to Sacagawea, who spoke in Shoshone to a leader of that tribe. And then the process reversed: Shoshone to Hidatsa to French to English.

Here’s an idea that we suspect no one else has proposed: this would be a good time to adopt his chain of translation and put it to use to our world today.

There is no mistaking our national dilemma: people who are firmly committed to one political position are unable to communicate with people who are firmly committed to an opposite political position.

Lewis and Clark offer us a promising technique.

A far-left progressive Democrat would speak to a centrist Democrat. The moderate Democrat would speak to a centrist Republican. The centrist Republican would speak to a far-right Republican, who could then offer his response to the centrist Republican, and that response would then move back along the chain.

After a few messages have traveled back and forth through the chain, the time would be right for a designated interpreter to step in. Asking everyone to pause, the interpreter could ask everyone a few debriefing questions: “What did you just hear? Was it what you expected to hear? Where do you agree and disagree? Were there parts that you simply did not understand and that need more explanation? Do you need to keep using this chain of indirection, or are you ready now to talk with each other?”

Limerick has an interesting idea but in our forest world, I’m not sure our views fall into neat political categories whether three, four as in Limerick, or eight. Thoughts?

I just drafted an opinion editorial for a regional newspaper. There is a 300-word limit. Some papers have a 250-, even 200-word limit. To make needed connections and make my point, I had to generalize some, and omit lots of details. Clearly, someone with opposing views can think of details that I had to overlook, providing a reason to excuse the entire op ed. Point is, that some of the miscommunication and mistrust we see results from the need to (try to) communicate in sound bytes (pun intended). The media participate in the problem in order to be read or heard by a large portion of the public that wants simple, short answers, and due to staff and budget limits. Much of the public is not geared to critical thinking. Our educational system is failing to produce those critical thinkers. — Criticism is easy, solutions are not.

Hear! Hear! on the point of critical thinking lacking in our conversations. I advocated that point many times during my FS career, especially when artificial time constraints were imposed. The running joke was (and still is) we don’t have enough time to make a reasonable decision, but we have enough to redo the decision when the first one fails. And wouldn’t that be the operational principle to efficiency? Doing something only once?

As for the “interpreter” idea, I have seen that in operation during collaborative discussions. But, it took having a facilitator who could listen to the conversation and discover occurrences when people talk past each other. Ultimately, it was a worthwhile approach, but it also took time. Hence, my “time constraint” criticism above.

Small comment, but: I find it problematic for interpretation of people’s responses about their trust in different media that cable TV journalism is lumped with print (or, ostensibly print! I read it all online) journalism in the first graph.

If asked about the specific news sources listed separately, I would say I feel that the news side of the WSJ and the NYT “tell the whole story” and that MSNBC, CNN, Fox, and Daily Wire do not.

I do not think that any cable TV news outlet tells the whole story- nor do they truly attempt to.

(It is also problematic that these news sources are not distinguished by their ‘news’ vs ‘editorial’ content, but that is probably splitting hairs for 90% of the public… sigh.)

Actually my issue was exactly that – the need to distinguish news from opinion, and I think it’s a problem that the public can’t tell the difference (and this survey apparently didn’t try to). I’d like to see all of these companies make it more clear which one we are seeing – and maybe even stick to one or the other. (I think Associated Press and Reuters have stayed pretty factual.)

Then there’s the concept of “full story.” There is also “bias” in what news is covered at all. I think there is more legitimacy in Fox covering what I think are uninteresting stories because their audience is not like me, than skewing and ignoring facts about what they do choose to cover.