I became acquainted with them because they fund the State of the Rockies polls, the questions of which seem to lead toward conclusions that the group supports (IMHO), and are then used in a variety of outlets and op-eds to support those views in a seemingly coordinated strategy. So I was looking around for what else they do, and ran across this wildfire strategy.

Prescribed fire policy and management. Prescribed fire, also referred to as prescribed or controlled burning, involves intentionally lighting a fire in an area after careful planning and under controlled conditions to achieve specific natural resource management objectives, such as wildfire risk reduction, improved water quality, or improved wildlife habitat. Prescribed fire is currently underutilized as a management tool that can be safely used across private, state, and federal lands, including near developed areas, under the right conditions.

Tribal leadership. Tribes throughout the United States have used fire as a resource and cultural management tool since time immemorial. After European settlement, Indigenous communities were largely prohibited from continuing their fire management practice, yet many remain uniquely positioned to provide leadership on wildfire policymaking and practice.

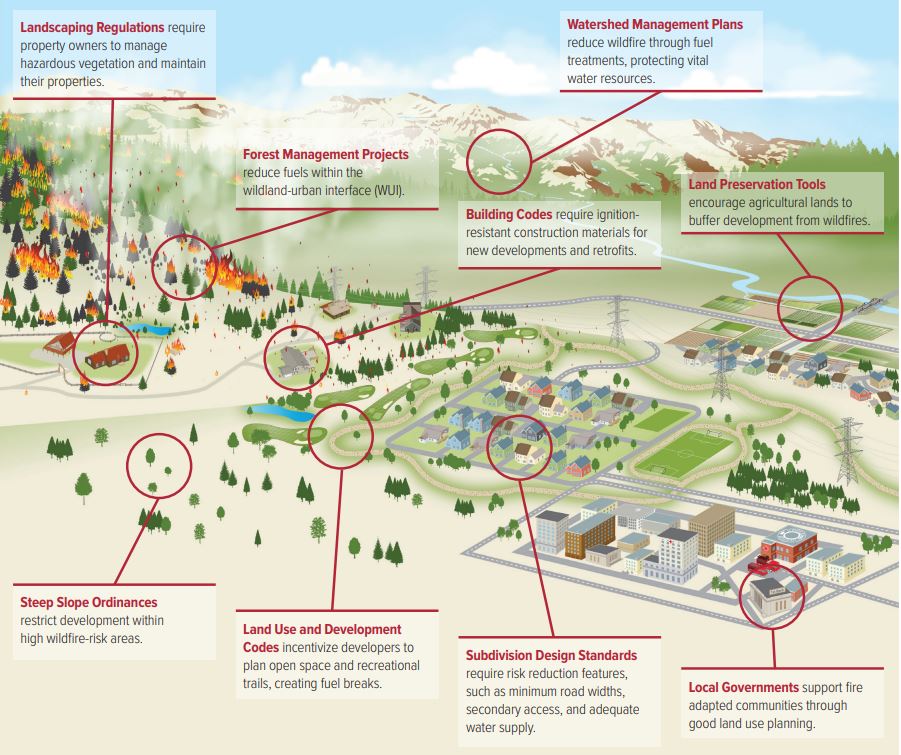

Land use planning in the wildland-urban interface. Many communities in the Western United States were and continue to be developed with little to no regard for meaningfully reducing wildfire risk. Recognizing that fire is an inevitable and often necessary part of the landscape through the West, communities must become fire adapted. The alternative is continuing to lose life and property to extreme wildfire events. Land use planning includes a variety of tools local governments can use to better prepare its existing and future communities for wildfire risk.

While prescribed fire is the star, mechanical treatment is also involved. They also have grants for improving agency decision-making, and use of woody material.

Hewlett’s strategy will focus on encouraging use of prescribed fire because it is one of the more effective and cost-efficient means of managing vegetation for multiple purposes, including hazardous fuel reduction and ecosystem restoration or maintenance. Unlike managed fire, prescribed fire can be used near developed areas and across private, state, and federal lands, and it can be done at times that mitigate communities’ exposure to smoke. Prescribed fire also reduces surface fuel to enable easier fire management, which mechanical thinning may not do. In some cases, prescribed fire should be used in conjunction with managed fire and/or mechanical thinning.

….

Grantees can help ensure that land management agencies are using the best available decision-making tools and policy options to improve strategic planning, access existing capacity, and track resource use.

……

For example, the foundation will support grantees exploring innovative funding mechanisms through development of industries that utilize the types of woody materials that come from forest thinning.

Sounds like some folks we know may be eligible for these grants..

I keep hearing that (all?) indigenous people expertly applied fire to “manage” their landscapes and that we should defer to their ancient knowledge/wisdom. But, who/where are the indigenous elders who possess(ed) this knowledge? Have the specifics of intentional indigenous burning practices and its application in different scenarios been recorded in any detail in extant books or recordings? Or, is it limited to verbal recollection and word-of-mouth over many generations? It would seem to me that much of the particulars would have been lost or forgotten over time, and a blanket statement that indigenous people were more expert is an empty and possibly spurious claim. Of course, I do agree that indigenous people possessed a profound wisdom which allowed them to live in greater harmony with nature than does our modern attitude. But, the “devil is in the details;” sweeping generaliztions about how (modern) indigenous descendants should be consulted because they know more about how, when, and where to utilize fire is highly questionable, since specific expertise may no longer be available, or even applicable, given the current extreme conditions of rapid climate change and expansive human development. It sounds great to say we should be following ancient indigenous fire practices, but what exactly does that mean? Or, does it just serve as a great soundbite?

Michael, I think in some cases, people in Tribes have a more or less continuous information flow from those times but others do not.

The way Hewlett talks about it, it’s a grandiose thing “yet many remain uniquely positioned to provide leadership on wildfire policymaking and practice.”

But in the linked article, Bill Tripp, an experienced guy with (apparently) the right quals wants to be able to lead a prescribed burn on “federal” land, a much smaller ask.

“We know the solution is to burn like our Indigenous ancestors have done for millennia. But too often we are told we can’t burn. Simply put, it’s either because we don’t have the proper environmental clearance for burning under the National Environmental Policy Act, because of liability or because there aren’t enough personnel available to supervise the burn. This year it is because smoke will be bad for Covid-19 patients.

These are excuses, not solutions. We carry the same qualifications as the federal and state agencies when it comes to prescribed burning or otherwise managing fire, and we hold the Indigenous knowledge that is needed to get the job done right. We have the knowledge to conduct cultural burning that is perfectly safe, and in many cases, we do not even need fire lines. Yet the federal agencies still do not allow us to lead prescribed burns on lands administered by the National Forest System.”

During my previous life as a reforestation contractor, my crews did about 18,000 acres of prescribed burns in western Oregon, at low cost and no real problems. Usually excellent results for subsequent planting and greatly reduced risk of future wildfires. So far as I know, not a single acre has burned in a wildfire since, and a large number of the plants have already been logged. Then in 1988 seven people got killed in a car pile-up on I-5 near Albany while driving into thick smoke from a field burn, and everything began to change. State and federal regulations started being written and enforced and within a few years, broadcast burning became too expensive and problematic to continue. The major fires that have been getting larger and more frequent in western Oregon began about the same time, in 1987, in part due to developing management restrictions on “buffer strips,” Wilderness areas, and ESA “critical habitat” zoning — and prescribed burning.

So far as indigenous knowledge, I think some of the Tribes in northern California have been taking the lead on this. My good friend, Frank Lake, is a Karok Indian that attended OSU grad school the same time as me, while we were both conducting our PhD research on “Indian burning” history and practices — him in northern California and me in western Oregon. The oral traditions of western Oregon tribes regarding these practices don’t exist and memories would have to extend more than 150 years since they were stopped. The most useful tools for reconstructing those practices and patterns are GLO survey notes, historical maps and photos, eyewitness accounts, and current vegetation patterns, in my experience.

I have been reviewing some of the literature on past indigenous fire deployments, and I believe we still have much to learn. There’s a great need for more research and documentation on historical indigenous burning practices. Some books that I’m thinking of reading are:

Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest – March 1999 by Robert Boyd (Author)

Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape 2nd Edition – February 2002 by Thomas Vale (Editor)

Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness – February 2009 by Omer C. Stewart (Author), Henry T. Lewis (Editor), M. Kat Anderson (Editor)

… and the soon to be released:

Indians, Fire, and the Land in the Pacific Northwest – September 2021 by Robert Boyd (Author).

Of course, there is the ever-popular:

Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources – October 2013 by M. Kat Anderson (Author)

One critical source that I have encountered, however, questions many of the accepted dogmas relating to the scope and intensity of purported historical indigenous burning practices:

Indian Burning Myth and Realities, By George Wuerthner

https://rewilding.org/indian-burning-myth-and-realities/?fbclid=IwAR2s6xEVL9oh9qphKS-pKLl34rPDt9SbVzXYJWdeYdc55VRER1XFvfnnEkk

The latter website has a wealth of peer-reviewed research and citations that raise many important questions worth contemplating.

I guess my main point is that we should be critically assessing all claims before we promote them as proven solutions without acknowledging that some strict and qualifications and limitations are in order. Pyro-forestry is still in its infancy as a (modern) science.

Hi Michael:

This is an excellent reading list. Anderson, Boyd, Lewis and Stewart are the experts on this topic for the geographic areas that they cover. I was assured by two of the contributors to the Vale book that the intent was to contradict Boyd, and I think that is fairly accurate. Some of the Vale scholarship, as a result, seems tainted by that bias. In my opinion, Wuerthner has always had that problem, too — there is a strong bias to his perspective and that can be seen by his selection and treatment of his references.

Wuerthner and I have debated issues about forest management on-and-off for many years, and I have mostly stopped reading him as a result. This is different. He is writing about a topic that was the focus of my graduate research and in skimming the contents, there is a lot of misinformation in what he is stating. Again.

In the next day or so I hope to post a fairly thorough review of Wuerthner’s work on this topic. If you want to add to your reading list — and don’t want to pay for the book through Amazon — you can download my dissertation here: http://nwmapsco.com/ZybachB/Thesis/Zybach_PhD_2003.pdf

Thank you so much for the link to your (475 pg) dissertation, Bob. You have certainly researched the topic intensively. I am looking forward to reading it, and some of your other work as well.

P.S. I just completed my own graduate studies (not a Ph.D.) in Urban Forestry at OSU.

thanx

mike

Hi Michael:

Please send me an email. It might take me a little longer than expected to review the Wuerthner article — it doesn’t have a date and these are nearly identical statements that I personally debated with him by email in 2009. I’ve left a phone message for him on his phone to clarify (not sure we’ve ever actually talked before), so waiting to hear back before progressing.

Given your reading list, you might be surprised at how he responded to me on January 5 of that year: “I have read Vale’s book, but I will try to find Forgotten Fires, and Boyd’s book.” I am hoping he did just that.

In the interim, and instead of wading through my dissertation, here is the 15-minute slide summary (starting at 4:30) that summarizes my thoughts and research on this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVSnCs9LxeY

Go Beavs!

Thanks for the citations Michael!