Jonathan Thompson runs a newsletter called The Land Desk that covers some of the topics of the Interior West that are also of interest to TSW readers. This story is about the issue of non-motorized recreation impacts on wildlife, and collaborative efforts to deal with that issue.

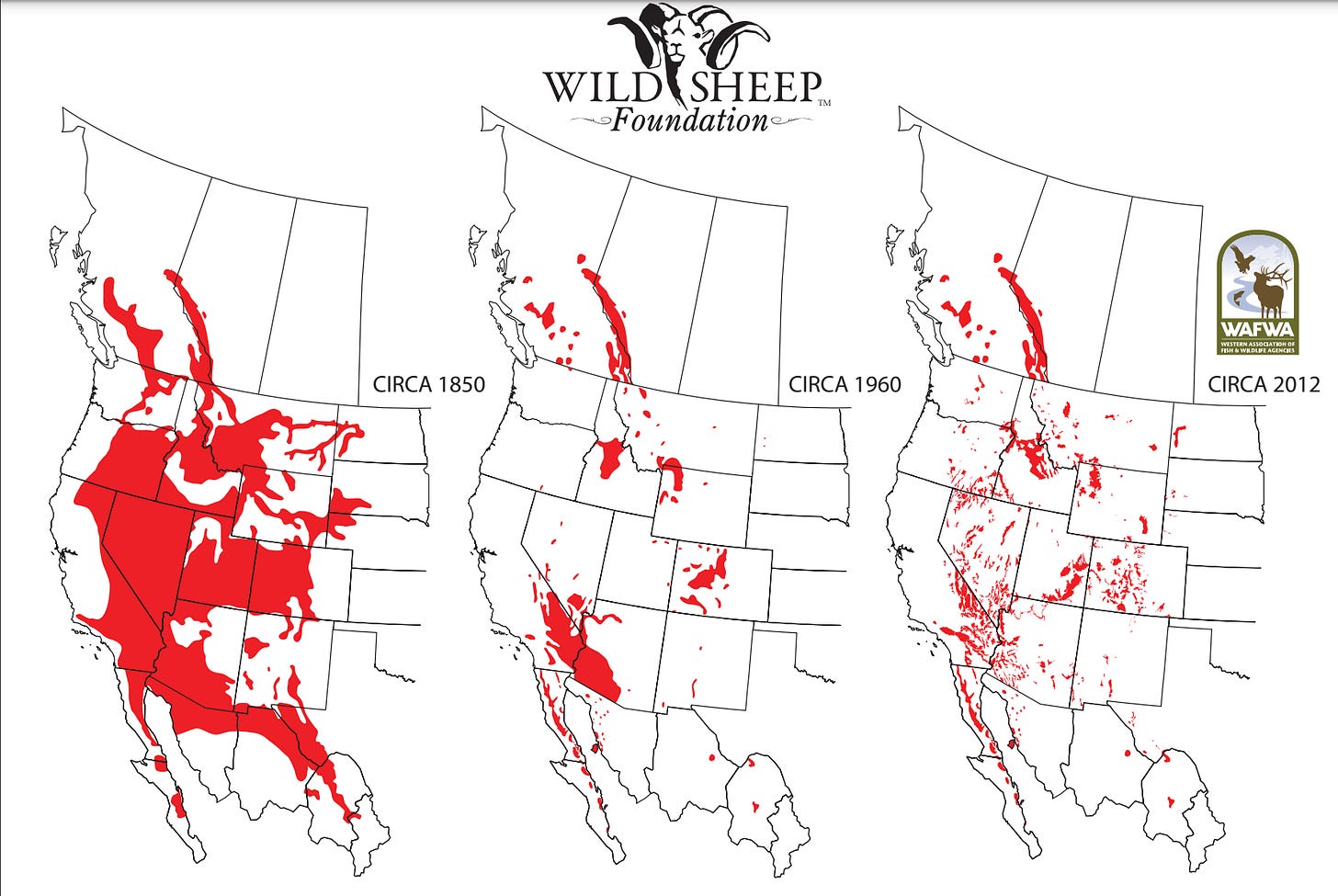

(what’s interesting about these maps to me are the dots that weren’t there in 1960 but are there in 2012; fewer blobs but expanded numbers of dots in other places, does anyone understand this?)

CONTEXT: Bighorn sheep were once abundant across the Mountain West, migrating for miles to follow the forage. Habitat destruction, fragmentation of migratory paths, disease, climate change, competition from non-native and domesticated ungulates, and, well, humans in general, have shrunk the ungulates’ range and winnowed their numbers. The Teton Range’s bighorn sheep, hemmed in by humanity, stopped long-distance migration eight decades ago. The last remaining herd, numbering just 100 to 125 animals, is on the precipice of extirpation. In the 1990s, state and federal wildlife agencies, biologists, and advocates formed a working group to develop strategies to stave off its demise.

In the decades since, an additional threat has emerged: a growing number of recreational users going further and further into the backcountry — and the bighorn’s winter range. “Quiet,” non-motorized forms of recreation were once considered benign, but a growing body of research suggests even hiking and skiing can have a deleterious effect on wildlife.

To better understand these impacts, the Teton bighorn sheep working group teamed up with University of Wyoming biologists on a research project. The results — published by Alyson B. Courtemanch in her 2014 Masters thesis — were eye-opening:

“We found that bighorn sheep avoided areas of backcountry recreation, even if those areas were otherwise relatively high quality habitat. Avoidance behavior resulted in up to a 30% reduction in available high quality habitat for some individuals. Bighorn sheep avoided areas with both low and high recreation use. … These results reveal that bighorn sheep appear to be sensitive to forms of recreation which people largely perceive as having minimal impact to wildlife, such as backcountry skiing.”

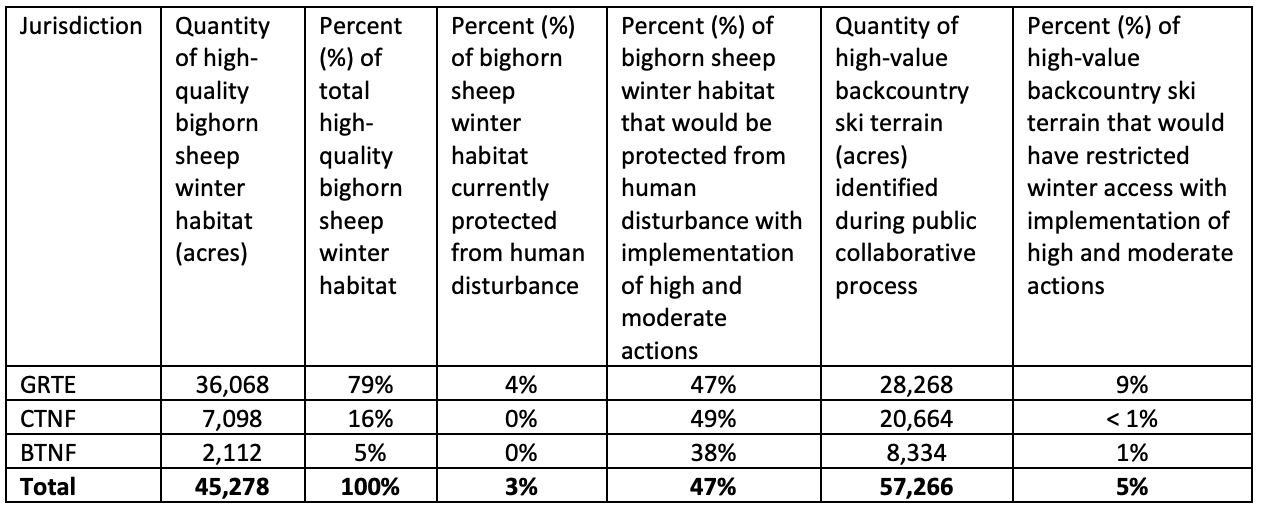

Given the urgency of the situation, such a finding might warrant an immediate closure of all 45,278 acres of the sheep’s high-quality winter Teton range to human incursion. Such a move wouldn’t fly with large sectors of the backcountry community and the businesses that rely on it. So the working group launched a bottom-up, years-long collaborative process to develop a strategy.

The resulting compromise: A little less than half of the high-quality sheep range—or 21,233 acres—would be closed in winter. The closure would only affect about 2,000 acres, or 5 percent, of the 57,000 acres identified as high-quality ski terrain. Here’s the breakdown:

So, in other words, the skiers are getting 95 percent of what they want while the imperiled bighorn sheep get just 47 percent of what they need to survive. But are the skiers satisfied? Most, yes, or at least they are grudgingly accepting the outcome. But a vocal few are grousing about even this small sacrifice, as reported last week by

…

and the story goes on to report on different peoples’ views.

Well this certainly confirms my suspicion that once environmentalists have managed to ban motorized recreation somewhere, they will eventually try to ban all human recreation on public lands. This is the inevitable result of an anti-humanist worldview that values animals over people. The rights of Americans to enjoy our public lands must always be sacrificed “to protect the wildlife.”

I think the science is highly suspect here too. If bighorn sheep so strongly avoid areas with any human presence, why then (at least in Colorado) are they frequently seen along major highways and around crowded recreational sites? I once saw a whole heard wandering down Guanella Pass Road during peak fall color season. They are are also known to hang out in Waterton Canyon right next to Denver which is a popular hiking and biking trail that’s pretty much always crowded, especially on weekends.

The idea that bighorn sheep avoid humans at all costs just doesn’t square with even a cursory knowledge of their behavior.

https://jhwildlife.org/why-do-bighorn-sheep-lick-your-car/

“A common sight near Miller Butte in the winter is bighorn sheep licking or eating dirt on the road, as well as licking passing cars.”

But then I read this article…

““Quiet,” non-motorized forms of recreation were once considered benign, but a growing body of research suggests even hiking and skiing can have a deleterious effect on wildlife.”

Hiking has a deleterious effect on the sheep but they’re also known to lick passing cars. The idea of recreating a pre-human environment sounds nice but an episode of “Life After People” type solution is not the way.

Patrick, I think that’s a great question.. I’m thinking (1) there’s something about winter in the Tetons that’s different from Colorado and/or (2) the bighorns in Colorado have had time to adapt to people.. possibly, the only people bighorn have seen in the past are hunters.. so to be avoided. Most of the people bighorns in Waterton Canyon see are not hunters, hence not to be avoided in the same way. I’m going to find a bighorn expert and ask them unless someone out there has a better idea?

George Wuerthner > Jonathan Thompson. Fight me.

What does that mean?

I read the abstract of the University of Wyoming’s masters degree candidate and Mr. Thompson’s essay on this issue.

I think it’s important not to dismiss the actual issue based simply on who’s advocating for these closures. I don’t know anything about Jonathan Thompson. Maybe he is an environmental fundamentalist. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the proposed winter closures won’t benefit the bighorn sheep. To me, it’s analogous to the old saw, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean that someone isn’t after you.”

It is worth wondering, though, how vulnerable the sheep are. I’ve seen them before at high elevations, though not anywhere near a road. If they really are hanging around paved roads, then what about that? Could both be true: they hang around paved roads and yet still they’re vulnerable? Perhaps. I wouldn’t discount it automatically.

In the San Francisco bay area, a public agency is contemplating prohibiting e-bikes within 100 or 200 feet of various species of bats’ nesting sites. It’s already causing a backlash. People are saying, What about loud hikers? They have a point. If the agency prohibits hiking too, the backlash will be all the greater.

Many years of bat work on multiple species – they care not a twit about your presence during the day around or even next to the roost tree even if you are blasting Metallica on your boom box. Now in a cave during winter, that’s a different story…. as per sheep. Then balance risks and come to roads to get salt which sometimes overwhelms their natural tendency to avoid humans.

Personally I will be staying out of bat caves, especially those in China.

The author is a graduate student, not an environmentalist (unless one considers anyone who studies wildlife an environmentalist). They used GPS location data from collars and standard statistical analyses to develop the results. The animals clearly avoided high quality habitat when it had high levels of backcountry winter recreation. This isn’t debatable, unless there’s something specific about the statistics they used or study design one can point to?

It is a common finding that individuals of some species can become habituated to some levels of routine disturbance, but flee or abandon areas when that same disturbance is novel or randomly applied. For example, there are bighorn studies showing that animals are much more likely to flee if approached by off-trail hikers/bikers than those on trails. This is true for other ungulates as well, where they do not habituate to off-trail uses.

In an era when western states are scrambling to preserve habitat for bison, wapiti, bighorn sheep, pronghorns, deer, the threatened greater sage grouse and all the other wildlife at risk to the Republican Party how is running nurseries for introduced species like feral horses and burros either conservative or sustainable?

Sharon, I don’t know that anyone answered your question about the expanded number of dots in 2012 compared to 1960. Those dots likely represent reintroductions of bighorns to areas in which they had previously been extirpated.

I found a Forest Service publication from 2001, which includes the following paragraph:

“Bighorn sheep recovery began during the 1960’s and 1970’s. State wildlife departments in

partnership with land management agencies have ongoing efforts that include transplants into

unoccupied habitat, augmentation of existing herds, and habitat manipulation. These efforts have had varying success rates; however, success has been consistently poor in areas where contact with domestic sheep occurred. Even with the ongoing recovery effort, current bighorn sheep numbers in the Western United States are estimated to be less than 10 percent of pre-settlement populations.”

https://www.fs.fed.us/biology/resources/pubs/wildlife/bighorn_domestic_sheep_final_080601.pdf

Thanks, John!

The dots Sharon asked about. Even though the species is considered at-risk, bighorn sheep are are heavily managed (with lots of state money behind it) because people still want to hunt them. They are now also vulnerable to disease spread by domestic sheep. They often get removed to avoid that, and they also get relocated to start new huntable populations in favorable habitat. This leads to dots in new places. And what Ben said about habituation (I can think of at least 3 herds near here that I’ve encountered on or near a road). So I suppose that a backcountry population could get used to heavy recreation use (at some cost to some individuals along the way) – but maybe that isn’t what the hunters want.

That makes sense but I am curious about how the intersection of OK, TX and CO could be favorable bighorn habitat, other than the absence of sheep..

I don’t know how perfectly accurate the “circa 1850” map in the article is, and according to some, bighorns are native to southeast Colorado:

“When travelers think of Big Horn Sheep, they generally think of the mountains—and they would be right—except for one small fact: big horn sheep are also indigenous to the canyons of southeast Colorado, and they are reproducing and thriving after being re-introduced to the canyons.”

https://www.canyonsandplains.com/outdoors/wildlife-watching

Comanche National Grassland has a number of cliffs and canyons that could suit bighorns well. It’s also possible that bighorns were introduced in areas they did not historically occupy, like mountain goats in the Olympics, Tetons, and Black Hills, but I don’t know of any specific locations where that occurred with bighorns.

Thanks, John! I’ll see if I can run down a Colorado bighorn expert to answer some of these questions.

Lots of interesting info in this assessment from 2007 for Region 2 of the Forest Service.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5181936.pdf

Patrick, this report has much info about the Guanella Pass, Mt Evans and Waterton Canyon herds.

Good find. I found this passage interesting:

“Other threats to the Waterton sheep are nearly as

dire as disease and habitat issues. Recreational use of

the canyon is high and is expected to remain so or to

increase. Motor vehicle access has been restricted, but

there have been numerous reports of sheep approaching

people and being fed or petted. CDOW has started an

education program to inform people of the problems

with human/wildlife interaction in Waterton Canyon,

and signs have been posted to discourage feeding or

approaching wildlife. Despite these efforts and others,

such as hazing by CDOW personnel, people continue to

interact directly with the sheep (Linstrom 2005b).”

That pretty much matches my experience seeing them in Waterton Canyon. The sheep don’t seem shy around people at all there. That report is probably correct that they are forced to come to the canyon bottom where the walking path is to drink from the river, but they have certainly become habituated to people. If they can get used to people and still live in places as crowded as Waterton Canyon, Mount Evans, and Guanella Pass, surely backcountry skiers are not going to seriously impact them. The report calls it a threat and assumes recreation will prevent the heard from growing to its original size, but it doesn’t actually provide any support for that assumption. I would think the others issues like lost habitat from the Strontia Springs Reservoir have a greater impact.

To me it seems like Bighorn Sheep are just the latest species environmentalists have latched onto in order to restrict recreation. It helps that pretty much everywhere in the west is considered bighorn sheep habitat. This is also a big issue with the ongoing BLM Labyrinth Canyon travel plan around Moab, where the entire travel management area is in desert bighorn sheep habitat and that’s going to be the main justification for most route closures. Just like with the prebles mouse and spotted owl, for species that are supposedly “endangered” they sure seem to be absolutely everywhere.