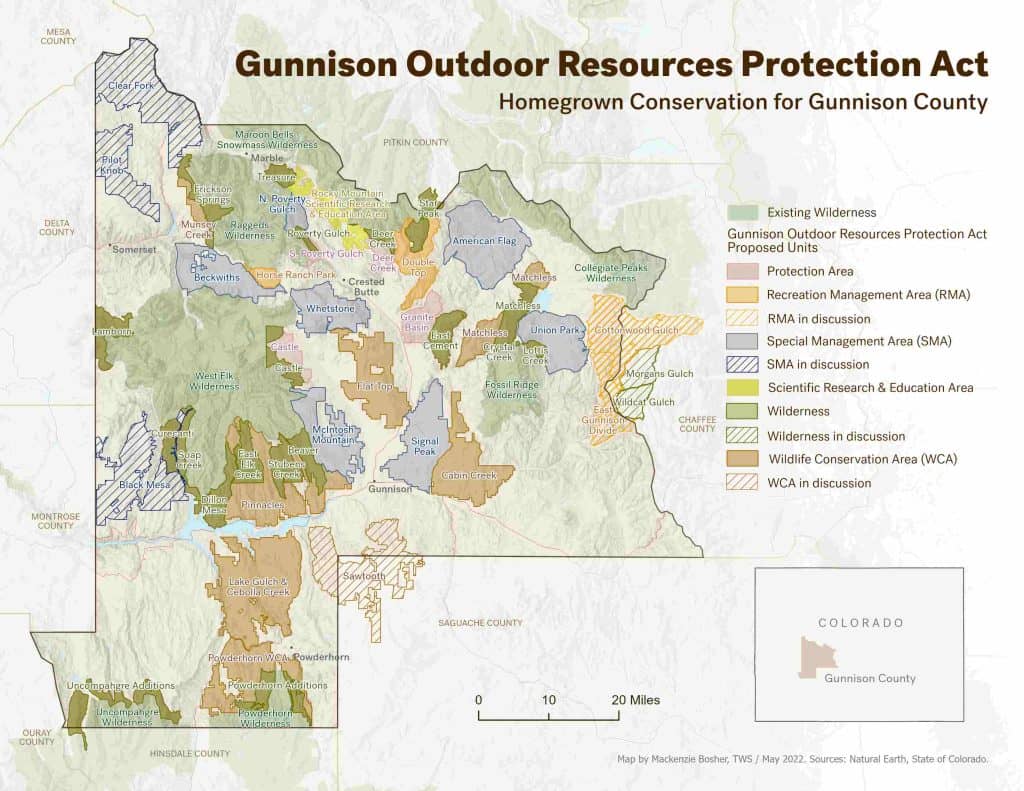

This is a proposal that seems to do land management planning for BLM and FS jointly in the Gunnison area. According to the website Bennet started effort this in 2012 (he was elected in 2010). It seems to have all the usual (local) suspects involved. And right now, this legislative proposal is even open for public comment! But no NEPA of course, and perhaps not much discussion of how entities outside of the area should influence federal lands. This reminds me of a Mark Rey quote about how deciding on designations is politically above the pay grade of a Forest Supe. It definitely changes the political landscape of decisions, and perhaps relieves the FS and BLM of the rigors of (and overanalysis, NRV-ing, and bullet-proofing) planning and EIS’s. Because isn’t the ultimate question, beyond all the high falutin’ verbiage, “who can do what. where?” Leaving the “how” perhaps to another day. And in legislation, if passed, it would stick.. or at least be an interesting convo and/or object of horse-trading in Congress. On the website you can find the readers’ guide, FAQ’s, the proposal and maps.

The only thing I would add is a public posting of all comments, so that folks like me might be able to write about what concerns people have. But maybe that’s there somewhere.

What do you think?

I always look on these things with scepticism, and it’s hard to keep an open mind when one starts out with biases.

It looks to me like a lot of recreation and probably zero camping areas with the hope that affluent recreators will stay in hotels in town and eat at restaurants. The same recipe that has been used at National Parks for eons. The list of businesses is very long. A couple special interest groups, bikers, off roaders, fly fishermen. Who is left out? Mining for sure, loggers maybe, do they even log in Colorado any more? I’ll bet e bikes aren’t in there. Probably not much consideration of the other 99.9% of the public.

I still hate when people use “impact” figuratively, as an intransitive verb.

I have actually always agreed with Mark Rey that forest plan decisions are above the pay grade of forest supervisors because of the political aspects of the decision, and maybe above a regional forester. I think Congress in NFMA may have passed a bigger buck to the Forest Service than it could handle, and I could see something like this legislation being a better idea, in principle. Congress reserved to itself the power to make wilderness decisions, and I don’t see other gross management designations being much different. I’m guessing the FS would fight this loss of authority, but it would also lose what it sees as a major headache in forest planning (and save lots of money).

I assume non-local interests would be represented in Congressional hearings by their usual representatives and lobbyists, but also that they would find a way to be represented in the local discussions as well.

Of course I have no idea if I would like the results (ignoring for the moment that it would end my career), and that kind of fear of the unknown on all sides might make it a hard sell. A test case may be worth trying. However, this example is not typical because it does not discuss commercial logging at all, which seems like it would (still) hang up such efforts on most national forests.

The way I think about commercial harvesting is like mining or whatever.. if it’s “allowed” people who don’t want it have another bite at the apple, at the project level. Or while this allows grazing, people who don’t like it can still take the agencies to court over a species or something else. That’s why some feel that those sorts of deals are quid pro (might possibly) quo, folks trade Wilderness (permanence) for the ability to do things in places.. but that negotiated-for ability can always be transcended by the whims of judges in court cases. And to do a deal on that basis is ultimately not a deal at all.

I don’t see how you can argue against a bite of the apple that contains the apple-specific information needed to understand how it’s going to affect you. The argument should be about the value of planning – whether and how to make a decision to let you try a particular apple in a particular place. (And you know where I stand on that one.)

I agree in theory Jon. But, in practice, Congressional knowledge of virtually anything extending beyond the last stop on a subway is virtually nil.

Here, there be danger. Just rake those tree farms, peasants.

There’s no public repository of comments on the GORP Act, but here is a link to the comments I submitted on behalf of Colorado Offroad Trail Defenders: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1G32h63okzPcfo7LJ88aRTkoc36e9xTDCaHyAtL7jYLE/edit?usp=drivesdk.

In short, I pointed out that because of a few mapping errors, Senator Bennet’s claim that no existing motorized routes would be closed by this bill is false. In fact parts of two existing roads and a motorcycle trail would be closed because they are currently mapped as being inside incompatible management areas. Hopefully these mapping errors will be fixed in the final bill, since it looks like they probably intended to exclude those routes but put the boundaries in the wrong place to do that.

Additionally, the two Wilderness areas in Chaffee County listed as “under discussion” would close two highly popular snowmobiling areas along Tincup Pass near Saint Elmo and one also conflicts with a recognized Chaffee County road which the federal government has no jurisdiction to close. Obviously neither Bennet’s staff nor the GPLI have done their homework on those areas, nor have they been subject to any kind of collaborative process like the rest of the areas in the bill, so I hope those are left out of the final bill.

Overall this bill, like most Wilderness bills, is pretty one sided. It gives environmental groups basically everything they want and the permanent assurance that the Gunnison Basin will be forwver managed according to their policy preferences. Disfavored groups like motorized users get to continue using these areas for now, but we have no guarantees or assurances beyond the fact that the land management agencies *may* continue to allow motorized use on existing routes, but have no obligation to do so. Meanwhile the main effect of the bill is to ensure that no new motorized trails may ever be built or re-opened in any of the new management areas, guaranteeing that motorized access in Gunnison County will only decrease over time.

Personally I think it would only be fair to give motorized users some certainty too by mandating that all current designated motorized routes in these areas must (not just may) remain open, but that’s probably too reasonable a compromise to ever be seriously considered.

That was my point about these kinds of agreements.. one side gets what it wants permanently and is traded for the other side maybe getting what it wants for now. And I think that would be easier to do with OHV and grazing (which are already there), since it is legislation. Tree cutting and minerals not so much as that particular project is not there on the ground yet, for the decision to be made that “we will accept those impacts in perpetuity.” I think it’s worth discussing, though, maybe we could have a sit-down with Bennet’s staff?

I don’t think “we got there first” is an especially good policy argument for the “greatest good.”

Why not? Especially when it comes to recreation? People have been enjoying these recreational opportunities for decades and rely on those opportunities continuing to exist. Why is it not the “greatest good” that legislation offer the certainty that existing forms of recreation will continue to be allowed?

What is the “greatest good” here anyway? This is a political process. The “greatest good” is whatever can gain majority support in Congress. That normally requires negotiation and compromise so that both sides have something to gain from it. Giving both sides certainty that their interests are protected is a great way to do that. Conversely, giving only one side certainty is not.

There are a lot of people who no longer think that allowing someone to unilaterally stake a claim on public lands under the 1872 mining law is in the best interest of society. The same is becoming the case in the drought-stricken west with its prior appropriation doctrine of water rights. Things change and the balance of interests needs to be considered, especially where it has never been considered before, and I don’t know why motorized recreation (often another unilateral decision) should be different. It would be appropriate for Congress to consider this balance here. (The same may even be true for Wilderness designations some day.)

I disagree with this characterization of “certainty” as being yes or no. There are degrees of certainty, and those degrees are simply part of the negotiation process. So is the importance of “squatters rights.”

Historical precedent has value. You can’t (or at least shouldn’t) just re-evaluate everything about how public lands are used every few years from a clean slate. The fact is that every existing use of public lands is there because at some point in the past the authorities that were deemed it to be for the “greater good” or in the best interests of society. No existing use arose in a vacuum, and there is no such thing as an existing use of public lands where the balance of interests has never been considered before.

Sure things change over time and may need to be re-evaluated, but overall the power of precedent means that existing uses should continue to be allowed absent a really compelling reason not to. But these days it seems these re-evaluations happen so frequently that one decision barely has time to be implemented before another process forces the previous decision to be re-negotiated all over again. This is especially the case with motorized travel management.

Every current motorized route in the Gunnison National Forest exists because it has been evaluated in at least one (likely multiple) travel management process that determined its benefits outweigh its impacts. Yet land managers these days don’t seem to care at all about historical precedent, and the result has been that in every new travel management process, motorized routes are in fact evaluated with about as close to a clean slate as there is. This means that motorized users never have any certainty that a route that was determined to have high value and should stay open in one travel management process will be kept open in the next process 5-10 years later. As a result, no route is ever safe, and we are always on the defensive having to constantly defend even some of the most popular 4×4 trails in the country against the constant threat of closure.

Contrast that with the conservation side, where land managers very much respect historical precedent. Once a higher level of protection is applied to a given area, that serves as a permanent floor and no option will ever be considered that lowers the level of protection. Once a road is closed, it can never be reopened. Once an area is determined to be “roadless”, no development can ever take place there, and it is only a matter of time before any existing conflicting uses are shut down so that area can eventually be designated as Wilderness. Thus most federal land management is a one-way ratchet always headed toward more restrictions and stricter “protected” statuses.

A bill like the GORP Act tightens the ratchet a bunch all at once, and gives preservationists as close a thing to absolutely certainty as there is. It then puts tremendous pressure on land managers to shut down nearby conflicting uses adjacent to protected areas so that they can then be expanded in the next bill or forest plan or whatever. So the assurances in the bill that existing uses will continue to be allowed ring hollow, because we know it’s not likely to actually stay that way for long. While I agree that certainty is a matter of degrees, if the other side gets 99% certainty and we only get 1% certainty, that’s not a very fair bargain.

I’m not arguing that existing uses shouldn’t be an important factor. It would be interesting if there were some research showing loss of motorized opportunities through travel planning. My impression is that the first travel plan likely did quite a bit of that (because the “balance” had not previously been considered, at least in a public forum), but that those plans would have inertia so that additional losses wouldn’t be the norm.

The comparison to the “conservation side” using roadless and wilderness isn’t really appropriate because the roadless and wilderness designations are much harder to change (more inertia) than travel plan (or forest plan) decisions.