Thanks to readers sent in this fascinating WaPo story Trees are moving north from global warming. Look up how your city could change. The graphics and mapping, as so often happens, are way better than the assumptions behind them.

There’s much to question there. For one thing, the article is talking about hardiness maps and so “people planting trees”. Beware of English in headlines! To most of us, “moving” is different from “being moved”. Active versus passive.

Modeled vs. Observed

Another obvious problem is that it’s not exactly clear that it’s all modeled changes. So not, “moving” but “being moved on the basis of models.”

In fact, modeled results are better than observed results, according to this reporter (!), who is admirably careful about being clear on modeled vs. observed.

Unlike the government’s official plant hardiness zones, which were released in 2012 and are based on temperature observations from 1976 to 2005, the projections shown here include a time range closer to the present day and allow for comparisons over time.

But my favorite topic, of course, is what the article says about tree adaptation. I’m not criticizing the reporter here. I also had trouble finding current experts; in fact it appears that forest genetics, like tree physiology, and forest entomology and pathology have become less cool over time, That’s just the way it is, universities have to keep up with trends of what’s cool or they won’t get funding. So no blame to anyone here, we are all parts of a system. But I will try to shed some light on this particular question.

Let’s think about this together and I’ll share some research.

Trees’ ranges adapt to change, but modern climate change is fast. Over the past century, the earth has warmed about 10 times faster than when it emerged from historical ice ages. With some difficulty, humans will adapt to global warming. For trees and the ecosystems that depend on them, adapting will be even harder.

Actually trees’ “ranges” don’t adapt to change, tree populations do. So let’s look at how fast climate change is happening.

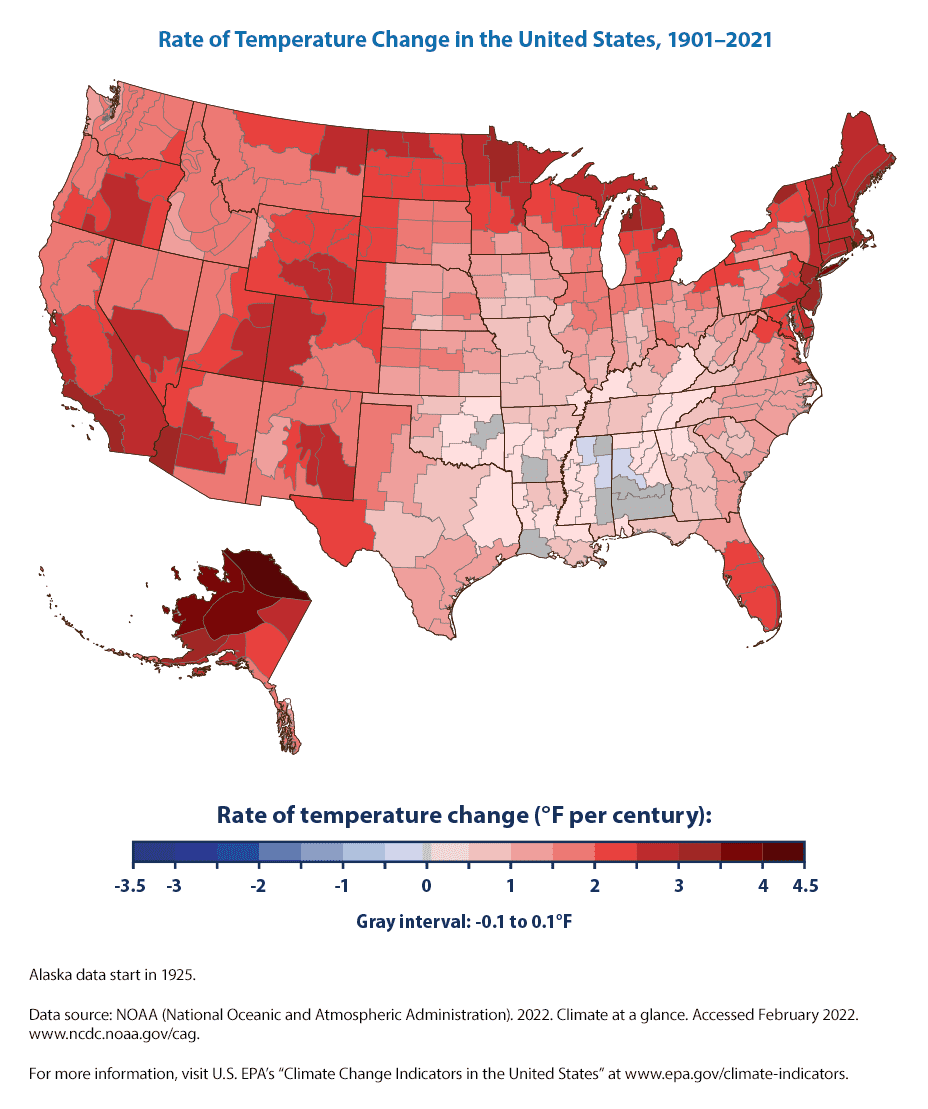

How fast? I found this on an EPA website. Note that they are observed differences over the last 100 years.

Since 1901, the average surface temperature across the contiguous 48 states has risen at an average rate of 0.17°F per decade (see Figure 1). Average temperatures have risen more quickly since the late 1970s (0.32 to 0.55°F per decade since 1979).

Some parts of the United States have experienced more warming than others (see Figure 3). The North, the West, and Alaska have seen temperatures increase the most, while some parts of the Southeast have experienced little change. Not all of these regional trends are statistically significant, however.

So there are two questions. First is “will the rate of change increase in the future?” .. I’ll ask some climate folks about that.

But the question that presents itself now is “are the observed differences too fast for tree species to adapt?”

We have historical evidence, and our own lived experience (of the elders among us) that there are many trees over 100 years old. In fact, the FS and BLM just mapped them for the MOG initiative! Which seems like evidence that not only populations of trees, but individual trees, have been able to survive the current rate of temperature change.

Caveat- average temperature is not particularly helpful to understand how tough trees find it to survive. The timing of frosts, cold extremes, season of drought and moisture, soil type, aspect, mycorrhizae, pathogens, competitors and so on..

The comments on the WaPo story point this out; also that more people seem to have problems with invasive pests and diseases than climate change. So what does looking at average temperature tell us? Probably not much.

I’ve seen them burn up. I’ve also seen them have tough times due to age (not a problem unique to trees- how do I know this?). For example, according to the Rocky Mountain LPP averages 150-200 years, thanks to this handy Fire Effects Information System (2003) compendium of info.

Silvics of North America also has good information. Biology hasn’t really changed.

Which reminds me of this box.

Time alone won’t kill a tree, but climate change might.

Unlike most living things, many trees can live indefinitely. There are trees among us today that took root before European settlers first arrived here. They have avoided fire, pestilence, drought and infestation, but some will not survive global warming.

Here’s what the cited paper says:

A preponderance of evidence has suggested that trees do not die because of genetically programmed senescence in their meristems (Mencuccini et al., 2014), and rather are killed by an external agent, either biotic or abiotic.

In the last 50 years, I’m not sure that I’ve observed climate change killing a tree, but certainly observed fires and bugs killing trees. And so, yes the 1980’s outbreak in Central Oregon may have been influenced by climate change (although at the time it was thought that was part of a natural disturbance cycle). Perhaps not so much bb outbreaks in the 20s and earlier.

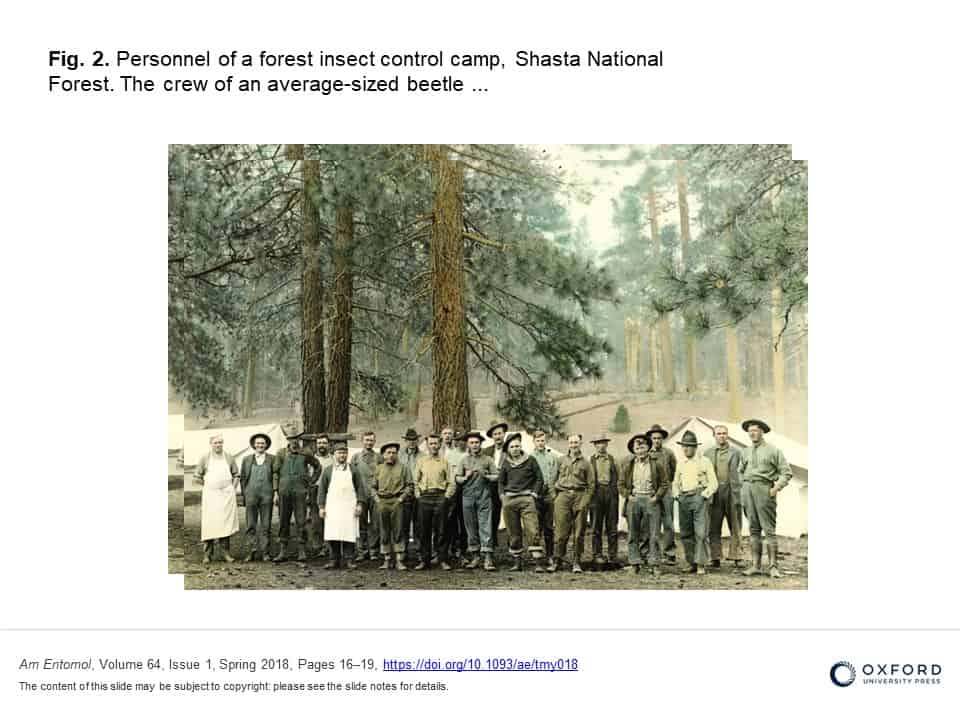

I found this fascinating paper on The Battle for Old-Growth Ponderosa Pine in Northeastern California: Efforts to Control the Western Pine Beetle in Remnant Old-Growth Stands During the 1920s

With terrific photos. Very, very cool.

The next post in this series will be on “some things we know about conifer genetics and adaptation.”

Sharon, I appreciate your many good questions and editorial eye for the wording miscues made by the writer of the WaPo article. This comment you made seemed like it needed a response though.

“We have historical evidence, and our own lived experience (of the elders among us) that there are many trees over 100 years old. In fact, the FS and BLM just mapped them for the MOG initiative! Which seems like evidence that not only populations of trees, but individual trees, have been able to survive the current rate of temperature change”

My understanding is that at least some of the modeling done concerning trees’ ability to survive climate change impacts (e.g., increased temperature, more frequent and severe drought, etc.) is not suggesting that mature trees with deep roots will die due to the rapid change, rather it will be increasingly more difficult for seedlings to establish and survive. Of course, a legitimate question is how accurate are the models.

Mike, that’s an important question. They never actually say, do they.. living trees, old trees, poles, will trees actually die if conditions change, or will their offspring die or be unable to become established? It might be true that it will be harder for seedlings to get established. Here’s what we have.. the seedlings are likely to be more adapted to changed conditions (I’ll talk about the mechanisms later). They may already have a hard time getting established, depending on all the physical factors that gave natural regen trouble prior to (the knowledge of) climate change. So for say dry ponderosa pine, seed sources in mast years, coinciding with presence of bare mineral soil. Seeds landing on it. Not getting eaten.. which are all pretty unmodelable. In a drive to go hiking and on a hike, I can see zillions of tiny pine seedlings in some places, and others not so much. In my neck of the woods there are summer rainfall patterns that may be the key to profuse vs. intermittent pine regen. Plus slope and aspect are big.. how about where you are? What do you see?

So the question is “how would you know?”

You could take a sample, say of different soil types and aspects, pick maybe 10 sites with a good number of cone-producing trees. Each year you would clear off some chunks of bare mineral soil.. perhaps along a shade gradient on each site. Then each year you would come in at different times to assess whether seeds had fallen, germinated, disappeared or sprouted and died at various points. If any germinate, sample soil moisture during the season. After say 5-10 years, you would know what factors are most important at the microsite level for seedling establishment. Then you would check with climate modelers to see whatever climate conditions that seem to be important to seedling establishment could be modeled at the microsite level.

I think in addition to seedling establishment, the challenge is seedling survival over several years until they can develop the root system needed to withstand extreme weather years. Modeling done on the Rio Grande NF now guides foresters as to which species to plant following harvests or disturbances. Time will tell if the process increases success with reforestation efforts.

What kind of modeling?

I commented about this once before. I’m basing this on my poor memory, so I may have some specifics incorrect. I sat in on two presentations, read the summary and spent some time looking over the maps, but I didn’t need to work with it in my position, so some of the specifics are a little foggy. Two FS employees (I think from GMUG) applied the range of conditions individual tree species survive within to a model projecting climatic conditions (I believe this was a mid level climate scenario) for the Rio Grande NF over time. This provided some rough predictions as to where individual tree species would most likely do well and areas where survival would be more challenging. RGNF foresters are using this info to inform their reforestation efforts.

thanks for this post and topic! I am glad to see you bring up that average temperature is of limited use – the extremes and other factors may be of greater importance. I have seen that several times in my career – things look good until there is a drought or a severe late spring frost. I also think that much of the discussion about trees and climate change seems to be centered on keeping things the same as they have been instead of figuring out how to adapt to the changes that may be coming. I look at the States of Oregon and Washington and how they are planning to deal with Emerald Ash Borer – ash trees are going to die – how are we going to deal with that? How will forests with Oregon ash reorganize after that? It’s not necessarily climate related, but I think that climate-related tree mortality is somewhat analogous. Trees are going to die – look at “firmageddon” in Oregon last year – how will those forests reorganize after the loss of those true firs?