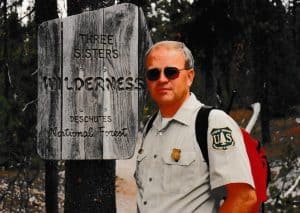

Les Joslin returned to U.S. Forest Service work in 1990 in the Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon.

A quarter century after the five Toiyabe National Forest summers he recently shared with The Smokey Wire readers, Les Joslin—a retired U.S. Navy commander—returned to U.S. Forest Service work. He did so in 1990 as a volunteer wilderness ranger on the Deschutes National Forest—a volunteer because the Dual Compensation Act of 1964 prevented retired regular officers of the armed forces from pursuing federal civil service employment without significant reduction of their earned retirement pay. Les served 10 summers in the Three Sisters Wilderness without federal compensation until Congress repealed the Dual Compensation Act in late 1999, then another four summers as a GS-5 forestry technician before he accepted a full-time GS-11 appointment as team leader for recreation, heritage, wilderness, special uses, lands and minerals, and roads on the million-acre Bend-Fort Rock Ranger District in which he served until shortly after his sixty-second birthday. “All the great stories,” he says, “happened during those 14 field seasons in the wilderness.”

A Three Sisters Wilderness Volunteer

By Les Joslin

During spring 1990, almost two years after I’d retired from the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C., and moved with my wife and two daughters to Central Oregon, I got wind of an opportunity to serve on the Deschutes National Forest as a Three Sisters Wilderness volunteer wilderness ranger. In addition to regular trail patrols, the person chosen for this position would conduct visitor impact surveys of every identifiable place anybody had ever camped along the trails and around the lakes of the roughly fifty-thousand-acre portion of that wilderness managed by the Bend Ranger District (later lumped with the Fort Rock Ranger District).

This wilderness, like the Hoover Wilderness in the Toiyabe National Forest on which I’d worked the summers of 1962 through 1966, was one of the original fifty-four designated by Congress when it passed the Wilderness Act of 1964 which established the National Wilderness Preservation System and provided for its management. A unique, closely-grouped cluster of four major volcanic peaks—the Three Sisters for which it is named and Broken Top—and surrounding Deschutes and Willamette national forest lands comprise the 286,708-acre preserve then administered by five ranger districts on these two national forests. I’d not had reason—other than compelling desire—to visit this wonderful area. This volunteer opportunity gave me that reason.

I applied, was interviewed and signed up, issued a uniform and a badge, oriented to my duties by a supervisory wilderness ranger named Deb, and soon on the job. As explained above, I began working on the Deschutes National Forest that summer of 1990 as a volunteer. I worked as a volunteer because this was work I wanted to do and knew I could do well. My five summers on the Toiyabe National Forest had included Hoover Wilderness patrols.

The work involved campsite condition surveys (pursuant to a “limits of acceptable change” management concept) and visitor contact in the Three Sisters Wilderness. This entailed walking to all the lakes along the trails—and cross-country to lakes not along trails—within the Bend Ranger District part of the wilderness. That’s a good-sized piece of country stretching from the popular Green Lakes in the north to the relatively isolated and much-less-visited Irish and Taylor lakes in the south, and westward to the Cascade crest.

Along those trails and around each lake I located all—or as close to all as possible—the places people had camped, then evaluated and recorded the impact of camping at each campsite on both the wilderness resource and the visitor experience. In addition to entering some thirty measurements and judgements reflecting those impacts and the condition of each site on a form that would eventually find its way into a computerized database, I sketch mapped and photographed each site. Assessing the situation along each trail and at each lake as a whole, I made recommendations regarding each site’s continued use for camping or closure for rehabilitation. The purpose was to produce a wilderness use and impacts baseline to inform wilderness management decisions.

And, as I traveled the trails, I represented the Forest Service and its management efforts to visitors and provided information and assistance they needed. Many visitors were surprised to see a Forest Service representative in the wilderness. Most were pleased.

By the end of that summer of 1990 I had worked twenty-five sunrise-to-sunset days, located and evaluated 254 campsites at 29 lakes and along many miles of trail, and pretty well learned the country. I had walked hundreds of miles, slapped thousands of mosquitoes that ignored my government-issued bug dope, and met 338 wilderness visitors.

In 1977 I spent a summer working in the municipal watershed for Dillon, MT (Beaverhead National Forest). It was mostly measuring flow and taking water samples, but I also worked on a campsite inventory using “Code-A-Site” forms – probably a predecessor.

There may have been an odd connection between those two multiple-uses. Towards the end of the summer I got some violent intestinal symptoms. Those were the days before anyone knew much about giardia, and I sometimes drank the water from the municipal watershed untreated while in the field (the iodine tablets provided by the Forest Service were not pleasant). When I eventually learned about giardia, I thought back on this and hoped Dillon was treating its drinking water.