We haven’t had much for our recreation friends lately.. so here is a link to a post by Jonathan Thompson in his Land Desk newsletter. Apparently he is not a fan of (some? all?) OHVers. Which is OK. Another writer might have said “OHV groups appeal decision which has had a lot of local input and compromise.” I mean this is a good argument (if true) but some of us could apply that to say.. the Rock Springs proposed RMP alternative, or numerous lawsuits against collaboratively produced fuels treatment projects. But do we know what litigants “really want”? I would say that we do not. This goes back to intention, and I’m not much of a fan of digging into other peoples’ brains.

The appellants claim the plan — which closes some motorized routes — violates federal law, is “arbitrary and capricious,” and is even unconstitutional.

But really they’re just miffed that they can’t continue to ride their OHVs just about everywhere.

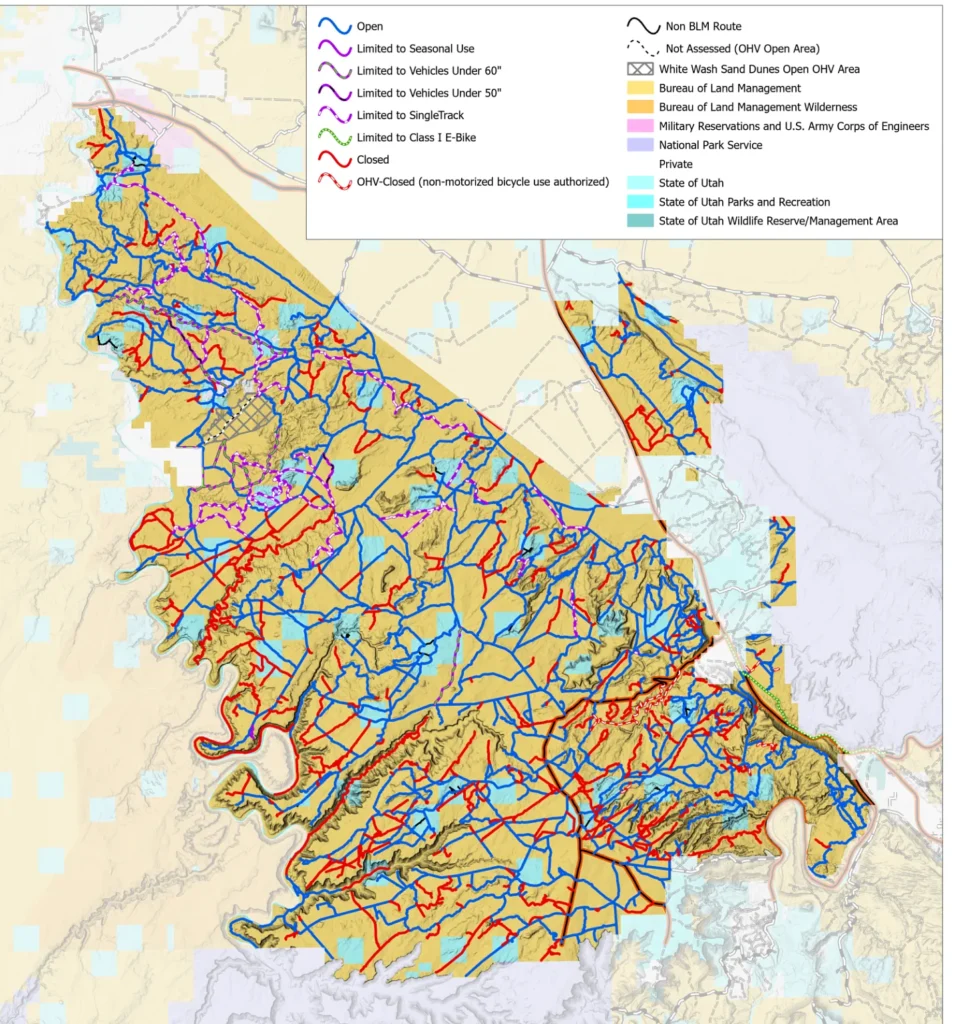

The plan, long in the making, was intended to strike a balance between motorheads’ desire for unfettered access and the urgent need to mitigate the impacts of a burgeoning number of OHVs, especially side-by-sides, on public lands. But even this “balance” was tilted toward the OHVs: Of the 1,120 miles of existing motorized routes in the 469-square-mile planning area, more than 800 miles will remain open to motorized travel. Only 317 miles, or less than one-third of the total, will be closed.

But the Blue Ribbon Coalition, other motorized access groups, and, for that matter, most Utah politicians, have an ideological intolerance to any road closures whatsoever — whether those roads go anywhere or not. The state and various county commissions have spent millions of dollars fighting road closures. They’ve led illegal and damaging protest rides into closed areas and subjected BLM staffers to threats and intimidation. County sheriffs of a certain ilk have even attempted to press criminal charges against federal employees simply for doing their jobs.

This case is a bit different, because the local county commission favors the BLM compromise. In fact, they advocated for a more restrictive plan that would have closed 437 miles of trails. In 2021, the commission urged the BLM to create a rational plan that would remedy the existing situation, in which 95% of the planning area was within a half mile of a motorized route and less than 1% was a mile or more away from a road. “In particular, it is important to provide opportunities for quiet forms of recreation, out of earshot of motorized trails,” they wrote. “We think the travel plan should ensure that a reasonable percentage of the planning area is more than one mile from a road or motorized trail.”

Instead of wielding ol’ RS-2477, the 157-year-old defunct statute giving the right to build highways across public lands to access mines, the Blue Ribbon Coalition and friends are attempting other spurious arguments, such as:

- The plan violates the Dingell Act, the 2019 legislation designating Labyrinth Canyon as a wilderness area. Congress emphasized that the act was meant only to protect the designated wilderness areas, not “to create protective perimeters or buffer zones around the wilderness areas.” The appellants claim this plan is an attempt to do just that. But the argument falls flat when you consider how many routes near the wilderness remain open. That’s no buffer.

- The closures violate the Constitution’s Appointments Clause. Okay, this one’s so goofy I’m not even going to get into it. (Basically they’re saying the BLM’s district manager doesn’t have the authority to make any decisions because they aren’t elected or directly appointed by the president).

- The decision is arbitrary and capricious. Not! The BLM has been working on this plan for more than five years and has accepted and considered thousands of comments. If anything was arbitrary it was the establishment of more than 1,000 miles of roads and paths across the landscape over the last century.

Chances of the appeal actually going somewhere are pretty slim, given these arguments. It’s a colossal waste of time nevertheless.

It would be interesting to hear the other side of the story. I’m hoping some TSW readers will weigh in.

Well I’m one of the plaintiffs in this appeal so I’m not exactly unbiased, but neither is this LandDesk article. Rather typical of a publication that accepts everything SUWA says as gospel truth. If you want a more balanced report on this issue, here’s an article that has that: https://www.deseret.com/utah/2023/10/30/23938967/moab-off-roading-updates-blm-gemini-bridges-labyrinth-canyon . If you want to read our press release on the appeal and download the actual appeal document, you can find that here: https://www.sharetrails.org/release-coalition-of-off-roaders-challenges-imminent-closure-of-317-miles-of-trails-near-moab-ut/ .

While there are many things I could say about this, I’ll start with this. If you actually look into the details of this plan (and I have spent the last three years practically living and breathing it), it’s clear there is nothing balanced, reasonable, or thoughtful about it. The only folks who think this travel plan is balanced are those who think absolutely everywhere on public lands must be dedicated exclusively to non-motorized recreation. The recreation balance around Moab already overwhelming favors non-motorized recreation, with two national parks, multiple wilderness study areas, and several huge mountain bike trail networks all dedicated primarily or exclusively to non-motorized recreation. This travel management area was one of the few areas around Moab, and indeed all of Utah, where motorized recreation was thriving, and has long been regarded as the ultimate offroading destination in America. That will no longer be the case, as this plan closed many of the absolute best offroad trails both in Moab and the entire country.

In Utah’s canyon country, and especially this area near Moab, the main scenic attractions are canyon bottoms and canyon rims. If you study a map of the closures, you’ll see that the BLM overwhelmingly focused on closing routes that were either in canyon bottoms or accessed scenic overlooks on canyon rims. Almost all motorized access to the banks of the Green River at the bottom of Labyrinth Canyon were eliminated, as were probably 70% of roads accessing scenic overlooks of Labyrinth Canyon and its side canyons. The 800 miles of routes that remain open are largely boring roads across open mesa tops with no technical challenge or scenic value.

Qualitatively, probably 80% of the most desirable trails in the area were closed, including dozens of routes that have been featured in published guidebooks for decades. The BLM also closed four Easter Jeep Safari routes, which the BLM has previously acknowledged are the absolute most desirable routes in the area and basically form the core of the OHV “highway system” around Moab. A few of the most popular Jeep Safari trails in the area remain open, but those were already overcrowded and will be even more crowded now that they are basically all that’s left of trails people actually want to use. Nearly all of the trails where you could get away from the crowds and enjoy a day of exploring remote, lightly used trails with spectacular scenery were closed.

The BLM’s reasoning supporting these closures were not thoughtfully considered in the slightest, but rather the BLM simply took an ax to the offroad trail network. It determined from the start that there were simply too many motorized routes in the area, and arbitrarily closed a third of them concentrating on those that were the most valuable and the most scenic. The primary reason they gave for the majority of the closures was the scientifically unsupported assumption that motorized use is incompatible with bighorn sheep habitat, which covered almost the entire TMA. Bighorn sheep habitat was the main excuse, but the underlying motivation was to manufacture wilderness suitability by closing most roads in or near lands deemed to have wilderness characteristics — even though the 2008 RMP determined not to manage these areas for wilderness characteristics.

The BLM also closed all motorized routes where certain vocal non-motorized recreationists had complained about motorized noise, even if those routes were in motorized recreation focus zones designated in the RMP. Thus in addition to expanding de facto wilderness areas, the BLM’s goal through this plan was to establish a precedent that non-motorized recreation always trumps motorized regardless of what the RMP says, and that any motorized route no matter how valuable must be closed if non-motorized users complain about noise, which the BLM considered to be a form of “user conflict” which must be minimized.

In the midst of all this, the BLM was extremely sloppy in actually giving reasoned explanations for individual closure decisions. Our stay petition highlights numerous instances where the BLM gave contradictory explanations for closures or made decisions based on blatant factual errors. In the most egregious instance, the BLM denied the very existence of an entire dispersed campground they themselves had created just a few years ago.

This was another instance like Rock Springs where throughout the planning process the BLM appeared to be planning to adopt the alternative positioned as “balanced” or a compromise and then swung for the fences and switched to adopting almost the most extreme conservation alternative at the last minute, and it shows in the contradictory rationale statements that often refer to other routes being kept open that were in fact closed.

The BLM closed all four-wheel drive roads paralleling the Green River, turning the river corridor into an exclusively non-motorized zone. Even though Congress had designated it as a scenic river, which allows roads, the BLM essentially decided to manage it as a wild river instead. And they ignored the fact that motor boats are allowed on the river itself, so closing roads along it will still not create the completely non-motorized rafting experience boaters were calling for. This also served to create a de-facto buffer zone along the boundary of the Labyrinth Canyon Wilderness on the other side of the river, in direction violation of a congressional prohibition. And these are just some of the ways in which the BLM outright ignored federal law in creating this travel plan.

In the end, we’ll just have to see where this thing goes. The appeal I’m involved with, led by BRC, is only one of three appeals I know of. Another is by the State of Utah based on their RS 2477 claims. I believe a second coalition of motorized access groups is also filing a separate appeal, but I haven’t seen that one yet. If the IBLA denies the stay petitions in these appeals, they will then move on to challenging the plan in federal court. Senator Mike Lee has also introduced legislation that would block funding for implementation of this travel plan and would bar the BLM from completing all the other travel plans in progress in Utah under the 2017 settlement agreement with SUWA. If that gets included in one of the upcoming spending bills in Congress, it could shut down the entire travel management racket in Utah.

Suffice it to say that this fight is just beginning. The LandDesk author may think we have little chance of succeeding (and I’ll grant the Appointments Clause argument is a bit of a hail Mary), but we only need to show likelihood of success on one argument at this stage in order to win a stay blocking this travel plan from moving forward. If this plan can be blocked long enough to carry over into a more favorable administration, it could very well be dead on arrival.

While anti-motorized groups accuse us of wanting to drive vehicles on every square inch of public lands, what we really want is simply to be able to continue driving historic dirt roads that people have been regularly using for over half a century. Nearly all of the roads in this plan date back to the mid-20th century and have since gained a special place in American offroading culture. Not everywhere has to be Wilderness, accessible only by able-bodied people capable of hiking dozens of miles at a time. Americans deserve to be able to access wild and scenic places by a variety of means, and for many, motor vehicles are their only way of experiencing these lands at all. We are not asking to build new roads into currently non-motorized areas. All we want is to keep the access we already have. This shouldn’t be so difficult for people to understand.

Thanks for giving your side of the story, Patrick! Also the link to the Deseret story..

“Peterson, with SUWA, said the group was “disappointed but not surprised” that the Labyrinth Canyon and Gemini Bridges plan is being challenged.

“Unfortunately, there are some who will not be satisfied unless every inch of Utah’s public lands are blanketed with off-road vehicle routes, regardless of the damage these vehicles cause,” Peterson said in a statement. ”

I guess SUWA is spreading misinformation.. or maybe it’s disinformation. Because we don’t know their intent. But they claim to know yours. And so it goes…

Yes, that statement is what I was responding to in my last paragraph. It’s ironic really, since their assertion would inherently mean we want to increase the total number of OHV routes. Motorized advocates know well that building new motorized trails hasn’t been on the table for decades. We only ever lose routes, and have indeed lost thousands of miles of roads in Utah already in just the last 20 years. Opening new routes, or even reopening a handful of previously closed routes, is simply out of the question.

Other user groups like mountain bikers have new trail systems built for them all the time. In fact in this specific area, a new mountain bike trail network was built in the early 2010s (shortly after the 2008 travel plan being revised here was adopted) called the Magnificent 7. Those mountain bike trails are intermingled, and in some cases co-aligned with, long established motorized routes, in an area designated as a motorized focus area under the RMP. Now the BLM is closing most of the motorized routes in that area due to alleged user conflicts with mountain bikers. And so it goes.

All we want is to keep open the few remaining routes we have left. In past rounds of travel planning the BLM at least focused mostly on closing unknown routes that few people used and most people never missed. Now that all those are closed, the BLM has started closing nationally famous trails that have long been featured in guidebooks and advertised as tourist attractions in themselves. If we can’t even have those, it shows that the powers that be have decided there simply is no place for motorized recreation anywhere on public lands in the west. This travel plan is an existential threat to our entire way of life, and both sides in this contest know that. If SUWA loses, they have plenty of other areas managed as wilderness in Utah. If motorized users lose, there will soon be no motorized access to public lands in Utah at all, and offroaders will be entirely relegated to a handful of private offroad parks as they already are in every state east of the Rocky Mountains.

If by “Congressional prohibition” you are referring to is the Dingell Act, its statement that this particular law did not intend to create a buffer zone says nothing about limiting the authority of the agency to do so. (Kind of like they are free to create “de facto wilderness.”)

Also, since Congress cannot dictate the outcome of a particular case, I have to wonder if it has the power to overrule a judicially approved settlement agreement (w/SUWA).

It’s interesting that you have described what you think the intentions of the agency are with regard to various roads. It seems like this is a case where the “reasoned explanations” required of the BLM by the APA will be important.

Agreed this will be a highly fact dependent case depending on the specific rationalle for the closure of each route.

This is the exact language from the Dingell Act:

“(B) Adjacent management.– (i) In general.–Congress does not intend for the designation of the Wilderness to create a protective perimeter or buffer zone around the Wilderness. [[Page 133 STAT. 640]] (ii) Nonwilderness activities.–The fact that nonwilderness activities or uses can be seen or heard from areas within the Wilderness shall not preclude the conduct of the activities or uses outside the boundary of the Wilderness.”

While it’s true the first part is a declaration on Congressional intent, the second part is a clear prohibition on using sight and sound impacts on the wilderness as reasons to prohibit motorized use on adjacent routes. This situation is a little complicated because in Labyrinth Canyon you have a wilderness area that ends on the west bank of a designated Scenic River, and then you have these motorized routes running along the east bank. The BLM expressly closed the roads because of noise disturbing boaters on the river, which is not itself in the wilderness but is immediately next to it, based on public comments from the boaters, environmental groups, and Grand County which explicitly called on the BLM to create a wilderness experience on the river. This also treats the river as a wild river instead of a scenic river. So the BLM arguably decides to treat the river as a buffer zone extending the wilderness area contrary to Congressional intent both in the wilderness designation and the scenic river designation, considering factors Congress did not intend it to consider, which makes the decision arbitrary and capricious. We’ll see what judges think of this argument but it’s pretty reasonable in context.

Are motorized boats allowed on that section of river?

Yes they are, which is what makes treating it as an exclusively non-motorized corridors so ridiculous. And as I understand it, the State of Utah controls what kind of craft are allowed on navigable rivers so the BLM doesn’t even have authority to ban them if it wanted to. There’s also an airstrip at Mineral Bottom that requires planes to fly through Labyrinth Canyon to takeoff and land, and that will remain open as well.

So, boaters in motorized craft complain about noise from motorized OHV’s? This is confusing.

I believe it was mainly the boaters in non-motorized craft (canoes and rafts) that were complaining, and I think the majority of boaters in the area are non-motorized, but yes it’s a very bizarre situation. This case should result in some interesting legal rulings on the interplay between wilderness, scenic rivers, and motorized use to say the least. All the roads along the river are also claimed as RS 2477 routes, so there’s that dimension as well.

Thanks for that additional info. Wilderness acts seem to come in different shapes and sizes. That does leave some room to prohibit uses for other reasons, like the (non-wilderness) experience of river floaters. And this does look like a good candidate for the courtroom.