Our friends at E&E News had a piece on it. What was interesting to me is the framing.

The Forest Service’s approach has rankled opponents of old-growth logging and those who say even forests that aren’t quite that old shouldn’t be heavily harvested. But the timber industry and its allies in Congress say the findings underscore a point they’ve made for years: that cutting down trees for wood products from time to time is a part of keeping forests healthy.

Coming from what we might call the areas with much need for fuel treatments and little timber industry (like much of the interior west), it seems like our voices aren’t heard in this debate. I don’t think the timber industry is looking for “heavy” harvests.. I think they are saying that they can use some of this stuff that is removed. This is the old dichotomy.. “logging” supported by “timber industry” and leaving things alone. I feel like the discussion could be back in the 80’s. The other people that aren’t heard in this framing are all those collaborative folks working on zones of agreement and trying to find common ground.

I’m going to quote from the E&E news summary which I think is good (but haven’t double-checked numbers).

1. Logging for timber is not as big a threat to old growth and mature forests as are wildfires, insects and disease.

In slides shared with forest industry representatives and provided to E&E News, the Forest Service said wildfires have eliminated 2.6 million acres of mature forest and 689,000 acres of old growth since 2000 on lands managed by that agency and the Bureau of Land Management. The agency defines old growth as areas that haven’t been logged, for instance, and mature forest as areas that may have been logged in the past and have grown back substantially on the way to becoming old growth again.

In the same period, 1.9 million acres of mature forest was lost to insects and disease, while 134,000 acres of old growth suffered that fate.

“Tree cutting,” which the agency said includes logging but might include other actions, took 214,000 acres of mature forest and 10,000 acres of old growth on Forest Service and BLM lands, the agency said. “Currently, wildfire exacerbated by climate change and fire exclusion is the leading threat, followed by insects/disease,” the Forest Service said in the slides. “Tree

cutting (any removal of trees) is a third relatively minor threat.”

But is, say thinning, a “threat” or is it “protection” from climate-change exacerbated drought or wildfires?

*************

Sidenote:

Meanwhile, this was not explicitly stated by anyone, but reminds me of an argument I’ve heard in different contexts.

Even if certain activities have only a little impact, those are the ones we can control, so we should further reduce them. Something like bats and white-nosed syndrome, or or many species and climate. It tends to be the same old activities that need to be reduced, based on this argument.

Or wildfire smoke and other sources of pollution.. “Smoke, Screened: The Clean Air Act’s Dirty Secret” as per this article, or this one.

The wildfires, though, could force the EPA’s hand. They could compel the agency to bump Chicago and East St. Louis to a higher nonattainment level and, as a result, trigger tougher remedial actions.

But obviously the remedial actions wouldn’t involve stopping the Canadian wildfires, it would involve ratcheting down the usual PM 2.5 suspects in that state.

*************

2. Back to the E&E news article:

In total, the inventory shows the 193 million-acre national forest system has about 25 million acres of old growth, 70 million acres of mature forest and a little more than 50 million acres of younger forest. The system includes grasslands and other landscapes.

Older forest is likely to increase over time as younger areas age, the Forest Service said. The increase, estimated at 5.5 percent by 2070 on Forest Service and BLM lands, will slow after that point, officials said, based on agency modeling.

******************

3. Timber Wars Redux…

To logging critics, the Forest Service’s analysis doesn’t offer much relief. “Current rates of logging are not the only indicator of the precarious state of older forests in the nation,” said Dominick DellaSala, chief scientist at Wild Heritage, a Berkeley, Calif., project of the nonprofit Earth Island Institute.

DellaSala said less old growth is being lost recently because harvests in decades past “nearly liquidated the entire ecosystem.”Barely a quarter of the nation’s old forests are in protected areas, as in designated wilderness, said DellaSala, who’s called for a halt to logging in old-growth areas. The U.S. needs a “national rulemaking process that protects all remaining older forests and large trees from logging as they are not safe from ongoing or future threats,” he said.

But about 30% are in Roadless, which are not apparently protected to DellaSala. Some people say this because they are not “permanent”. To my mind, as a person who has worked on a tediously litigated (no offense to readers who litigated) Roadless Rule, this is not a meaningful distinction. And 18% of NFS is Wilderness. So that adds up to 48%.

*************

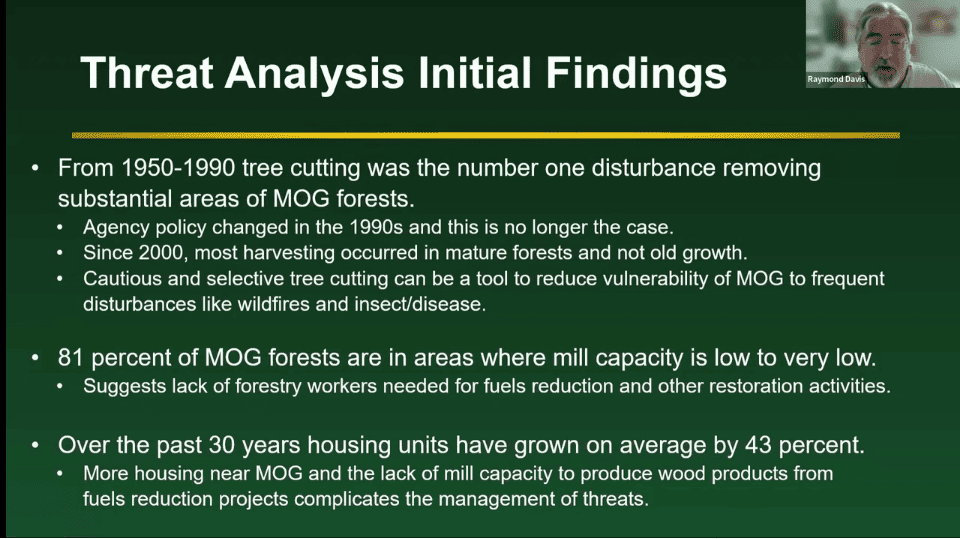

4. “As much as 81 percent of mature and old growth is in areas with little logging capacity, according to the agency.”

This is an interesting number. It could be interpreted as:

1. The timber industry wouldn’t have that much of an impact if we let them have at the 20 percent (not a popular interpretation, I grant you).

2. Folks who want to thin for mature and old growth protection (either fuel reduction or increasing drought resistance) are going to need megabucks, because currently there are not markets and viable substitutes for burning into the atmosphere. (We know this)

3. Maybe this isn’t really about logging? So maybe the controversy is between dry forest folks who want thinning (even with no industry available) and wet forest folks who don’t? It’s interesting that the article mentions the Tongass and not the millions of acres of MOG pinyon juniper from this fact sheet.

Pinyon and juniper woodlands are the most abundant forest type in the federal inventory of mature and old-growth forests, with 9 million acres of old-growth pinyon-juniper across BLM and Forest Service lands and an additional 14 million acres of mature pinyon-juniper.

4. Another framing than the aged and decrepit Timber Wars would possibly that Some Mesic/Coastal ENGOs exert an outsized influence over dry forest policy in their quest for a national MOG rule.

Other interpretations welcome.

I enjoy reading this piece. As you have stated, unplanned wildfires and other disturbances alter far more forested landscapes than anything else. Now, a quote that I thought was important. That is, “…But is, say thinning, a “threat” or is it “protection” from climate-change exacerbated drought or wildfires?

Well, it’s certainly not a “threat.” Large, high intensity wildfires throughout America – especially in the west – have created a national emergency. The three primary reasons are, with a tie for the top spot:

1. Lack of forest maintenance

1. The impacts of climate unpredictability

3. The expansion of the Wildland-Urban Interface

These three factors also enable the forest, or not, to be receptive to unplanned wildfire as a forest maintenance tool. Currently, America’s forests, especially in the west, are not receptive to fire being a maintenance tactics. In time, if the aforesaid “top three” are addressed, may they [i.e., forests] will be [receptive].

Until that time comes, the notions of “managed” or “beneficial” or “let burn” or “moving back to the next best ridge” are, well just notions without any hope of consistent success. As I have often stated before, they are just intellectual arguments.

As we move ahead to “On Fire”, please be careful of the “beneficial” fire focus. Simply put, it will not work. Not NOW. The focus has to be, expand forest maintenance and provide the necessary resources to that end. It’s not a close call actually.

Very respectfully,

I’ve always found it ‘odd’ that, on one hand, they say there isn’t much old growth left, while on the other hand, we are told that every logging project cuts irreplaceable old growth.

Then again, some conservatives want more “forest management”, and by that, they mean “overstory removal’.

To me, thinning from below is appropriate for many forests.

The current rate of loss of MOG from wildfire is greater now than it was pre-NWFP from wildfire and logging (tree cutting 🙂 ) combined (Healey et al 2008 – https://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/sites/default/files/lter/pubs/pdf/pub4200.pdf). The 80s were cool and all but if you can’t keep up with any developments over the last 30 years it might be time to retire.

Thanks, Patrick! I hadn’t seen that one..2008.. indeed. And here we are yet.

I didn’t go into it, but did they separate the “wet forest” part of the NWFP from the dry and what were the numbers? Here’s the abstract for those interested.

ABSTRACT

Interest in preserving older forests at the landscape level has increased in many regions, including the Pacific Northwest of the United States. The North- west Forest Plan (NWFP) of 1994 initiated a significant reduction in the harvesting of older forests on federal land. We used historical satellite imagery to assess the effect of this reduction in relation to: past harvest rates, management of non-federal forests, and the growing role of fire. Harvest rates in non-federal large-diameter forests (LDF) either decreased or remained stable at relatively high rates following the NWFP, meaning that harvest reductions on federal forests, which cover half of the region, resulted in a significant regional drop in the loss of LDF to harvest. However, increased losses of LDF to fire outweighed reductions in LDF harvest across large areas of the region. Elevated fire levels in the western United States have been correlated to changing climatic conditions, and if recent fire patterns persist, preservation of older forests in dry ecosystems will depend upon practical and coordinated fire management across the landscape.

Correlation does not equal causation, and “changing climatic conditions” have not actually been shown to: 1) be taking place in the PNW (other than normal fluctuations based on historical documentation), and 2) having anything to do with increased severity and extent of wildfires occurring on public forestlands.

However, there is a direct correlation between reduced harvest levels on federal lands and increased severity and extent of wildfires as has been accurately predicted by using traditional scientific methods for the past 30 years. If people were serious about saving our “MOGs” (OMGs?), they would actively manage for that result.

The conclusions of this study are accurate, but they are clearly flawed by politics. Cause and effect have been identified — and politically ignored — for decades.

Bob, you have no idea what you are talking about. There are dozens of papers that show the climate is changing the in PNW: snowmelt is happening earlier, ERCs are increasing, and the frequency of extreme drought periods is increasing. Your previous assertions that the past 100 years of active fire suppression has had no impact on fuel loads underpins the fact that you don’t understand basic fire ecology. It is frustrating that fridge voices from the left and right take up so much air space in the discussion of how to best manage our lands.

Patrick: Those “dozens of papers” don’t prove anything. I’m guessing modelers “peer reviewing” modelers. I’m 75 and the weather has been about the same during my lifetime and my research shows it’s been about the same for centuries. Not sure what an ERC is, but droughts were worse 90 years ago and lasted for decades in California several times during the last 1000 years. I’d go into more detail, but you are not using a real name, so my inclination is to not spend too much time responding. My doctorate is in ecology and the focus was on fire history. What are your credentials for telling me I’m clueless?

You are right that they don’t prove anything but I tend to trust papers that have gone through the peer review process and are based on actual measurements more than the opinions of an old guy on the internet. Everyone knows you have a liberal arts PHD Bob, you can’t help but mention that in every. single. post.

Thanks Patrick: I have written a detailed published report on peer review that was transparently reviewed by 18 named individuals, most with PhDs and several with national reputations, if you would like to read it. Based on your comments, I’m guessing no.

It’s odd that you mention that I claim to have a liberal arts degree in “every single post,” because I don’t. What are you reading that you think I’ve written? My degree is in Environmental Sciences — and I use my real name, making it easy to attack my age and actual credentials. Meantime, you continue to publicly make negative remarks about me while hiding behind a pseudonym. With no apparent credentials at all. Very brave of you. And why I give so little weight to what you have to say, and assume most others do as well.

Here was my main take-home (and it’s in this slide):

“Cautious and selective tree cutting can be a tool to reduce vulnerability of MOG to frequent disturbances like wildfire and insect/disease.”

Compare that to E&E’s description of the timber industry view:

“cutting down trees for wood products from time to time is a part of keeping forests healthy”

What jumped out at me (and what is missing from the industry view) was the “cautious and selective” part. To me that supports a default (plan standards) of not doing it, and deviation (plan amendment) should depend on site-specific proof of benefits.

It also seemed obvious that logging old growth (as opposed to MOG) is rare (10,000 acres after 2000?), and could easily be eliminated with a blanket prohibition. It could even be considered not suitable for timber production.

And maybe most importantly, while there seemed to be some surprise at how much MOG currently exists, there was no discussion of the historical context of that, which should be a basis of how much there SHOULD be. There wasn’t much discussion of the ecological significance of these numbers. It also wasn’t clear to me what assumptions they were making about management and fire when they projected increased MOG in the future.

I also noted that there was a slide showing how the temperatures in the Pacific northwest have increased over the last 30 years, in contrast to claims by some (who must not be named).