Yesterday we were discussing environmental justice and residents of dry forests. Jon said “Beyond the formal environmental justice realm (which does not appear to include “rural communities in dry forests”), this is pretty much a matter of opinion, and not a very practical criterion.”

I ran across this article in Wildfire Today which raises other questions. In addition to Jon’s question, I think pre-climate change, some people were originally not sympathetic to dry forest inhabitants (they shouldn’t live there). Now that wildfire is thought to be a result of climate change, though, it seems like attention has been drawn to the fact that low income people also live here. Which I think we knew, but…

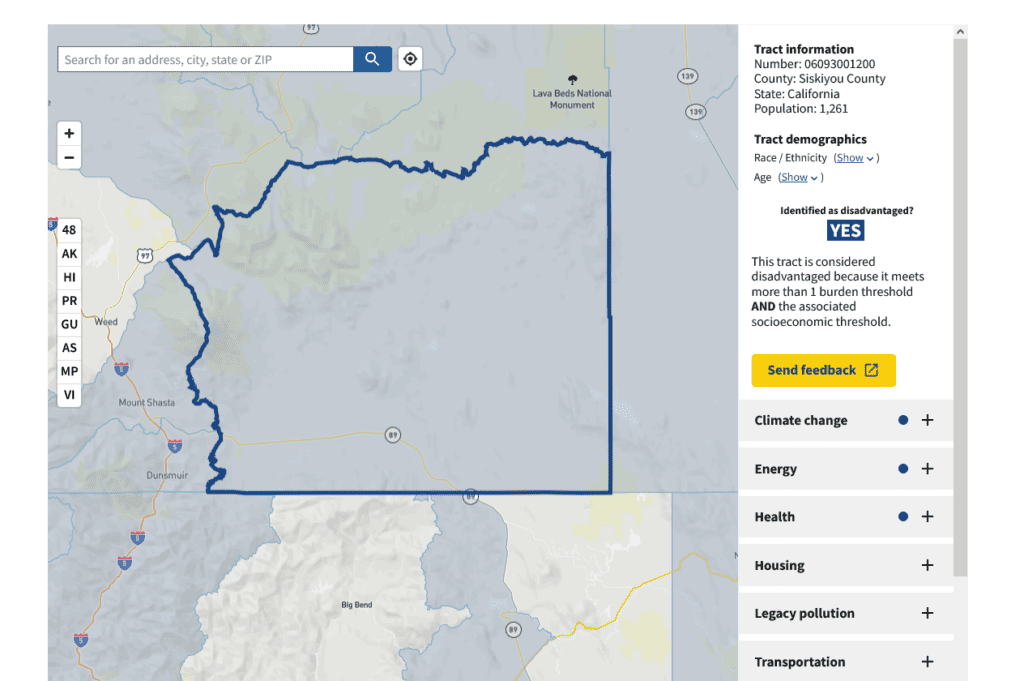

I don’t know about 90 percent of all people exposed.. maybe there is a map somewhere that shows it. Also how “exposed” is defined.

Around 90 percent of all people exposed to wildfires over the past 23 years lived in either California, Oregon, or Washington. Among those, researchers found a disproportionate number were poor, a racial minority, disabled, or over the age of 65.

A recent study examined the “social vulnerability” of the people exposed to wildfires over the last two decades. Social vulnerability describes how persons with certain social, economic, or demographic traits were more susceptible to harm from hazards including wildfires or other natural disasters.

From 2000 to 2021, the number of people in the western United States who lived in fire-affected areas increased by 185 percent, while structure losses from wildfires increased by 246 percent. The vulnerability of the people living there, however, isn’t well known despite these populations potentially never recovering after a disaster strikes.

Researchers asked whether highly vulnerable people were disproportionately exposed to wildfire, how vulnerability has changed over the past 20 years, whether population changes before a fire alter the vulnerability of the population, and whether social vulnerability of people exposed to fires was equal among states.

Each of the three West Coast states recorded disproportionate wildfire exposure of the socially vulnerable; Oregon and Washington had more than 40 percent of their exposed population being highly vulnerable while California had around 8 percent of of those exposed considered highly vulnerable. The most vulnerable populations were also those with low income, while age, minority status, and disability also affected populations’ ability to cope after wildfire.

The number of highly vulnerable people exposed to fire in the three states also increased by 249 percent over the past two decades. An increase in social vulnerability of populations in burned areas was the main contributor to increased exposure in California, while Oregon and Washington saw wildfires increasingly encroaching on vulnerable population areas.

“Our analysis highlights the need to increase understanding of the social characteristics that affect vulnerability, to inform effective mitigation and adaptation strategies,” the study said. “Particular attention to residents who are older, living with a disability, living in group quarters, and with limited English-speaking skills may be warranted, and cultural differences need to be addressed for effective policy development and response.”

Other research published earlier this year, The Path of Flames: Understanding and Responding to Fatal Wildfires, found unequal access and assistance could also play a role in who survives and who dies during catastrophic wildfires. In the study, researchers found that for many of the Paradise, California residents who died in the 2018 Camp Fire, the inability to evacuate on their own was a major factor in their deaths.

“… a disproportionate number were poor, a racial minority, disabled, or over the age of 65.”

In many rural areas — mine included — a decrease in “living wage” jobs in natural-resource-based employment, plus an increase in relatively well-off retirees, has had huge impacts on rural economies and demographics. In addition, the rapid increase in the number of short-term rentals means fewer long-term rental properties available for locals. Also, as well-off outsiders buy up rural properties to operate as short-term rentals, overall property values rise, and thus locals pay far higher rents for the long-term rentals that are available.

See “A town that became ‘one giant Airbnb’ is now facing a reckoning.”

https://www.businessinsider.com/hochatown-airbnb-broken-bow-lake-oklahoma-2023-11

FWIW, about one-quarter of the houses in my rural neighborhood are short-term rentals.

2 potentially relevant thoughts vis-a-vis Jon’s original comment, one more charitable, one less so:

More charitable: in stating the “formal environmental justice realm (which does not appear to include “rural communities in dry forests”)” he is correct, but absent context, this is kind of meaningless. “Formal EJ realm” presumably means where it’s gotten academic and policy attention, and that realm has largely but not exclusively grown out of dealing with the pernicious legacy of racially-gerrymandered neighborhoods and the siting of polluting, noisy, and otherwise health-and-wellness damaging things there. Fair enough, but it points to the need, perhaps, to expand said “Formal EJ realm” (and that is in line with what I take to be Sharon’s point).

Less charitable: in stating the criterion to be impractical he might be rehashing the fairly common (anecdotally, at least) line of thought that boils down to “it’s on you [socially vulnerable population in rural area], so don’t live there, then”. The reason I call this less charitable as a read is because that line of thought relies on prior judgements about where sympathy, resources, concern, what have you should be directed. It implies that one socially vulnerable population [say, a rural one] should have some form of agency to bootstrap their way around the problem (hence no need to be considered in the EJ rubric) whereas another socially vulnerable population would presumably not be expected to do so.

Wanting to be charitable given the overall value of this forum but nastier tone of recent months, I’ll make one slightly more editorial comment: I’m sure your average lower-middle class or poor person in say rural central Oregon or Montana would find great relief in being informed about their proportionally greater per capita representation in the Senate. That’ll make ends meet.

Sharon – does your idea come down to more comprehensive inclusion of social class (some kind of proxy metric for that) in defining “EJ populations”? Granted that some of that already exists in the EJ world, what would you add?

A.. I thought that the “overall nastier tone” might be more or less restricted to the Climate Change arena. But I’m curious as to whether your observations are different.

My point was only that anyone with situational awareness already knew that there were poor people in wildfire country; in fact, studies like this (from 2010 (!)) show that our programs at the time were not reaching them as they should.

This link is from Academia.edu and the title is The “Limited Involvement of Socially Vulnerable Populations in Federal Programs to Mitigate Wildfire Risk in Arizona.”

(sorry about the empty space)

I agree with you that a tool originally designed to deal with pollution might not fit wildfire risk communities. I’m thinking that perhaps the different kinds of communities would require a different kind of typology, perhaps similar to the Paveglio et al..

Because otherwise depending on the spatial scale used.. the rich and poor could be averaged to something meaningless. For example, take a resort community. Because of the high housing costs, poor people there might be even more worse off .. how to take that into account? Neighborhoods in some communities might not be so “gerrymandered” by race or poverty, but the community as a whole might be worse off. Using census block data might obscure important differences. In short..like so many things.. there are good intentions to help people. Yay!

But people who developed definitions were mostly concerned about local pollution loads and perhaps flooding..

So they did the best they could.

Now we are trying to splice in all kinds of different things.

Plus there are a thousand and one different agencies, states and NGO’s getting their own definitions and maps …

And of course, the big money ones (EPA and CEQ) are using data developed and not ground-truthed.

I’d call for a big “time out” and get all these groups together to develop an index. First clarify what are the purposes.. then develop one or more measures that best suit those purposes..

Here is the full quote from Sharon that I commented on: “Impacts of decarbonization efforts should not fall unjustly on, say, rural communities in dry forests, many of which may be disadvantaged in various ways.” It was not intended as an aspersion, but was simply about definitions. I believe “unjust” only has any value in objective decision-making if it is further defined, such as in the “environmental justice” context. Otherwise it is just an opinion based on someone’s set of morals. I think we agree that the rural west is not the context that has been defined as part of environmental justice.

I have no problem with looking at whatever effects are considered important (and giving special treatment if warranted, which maybe is the point here), but I’m not sure what “disproportionate” means as used here. The fact that there may be some amount of “disadvantaged” people who are “highly vulnerable” does not by itself suggest that there is anything disproportionate about that. (I suspect that the proportion of the general population that is “poor, a racial minority, disabled, or over the age of 65” is pretty high, maybe a majority.)