Here are a few of their conclusions:

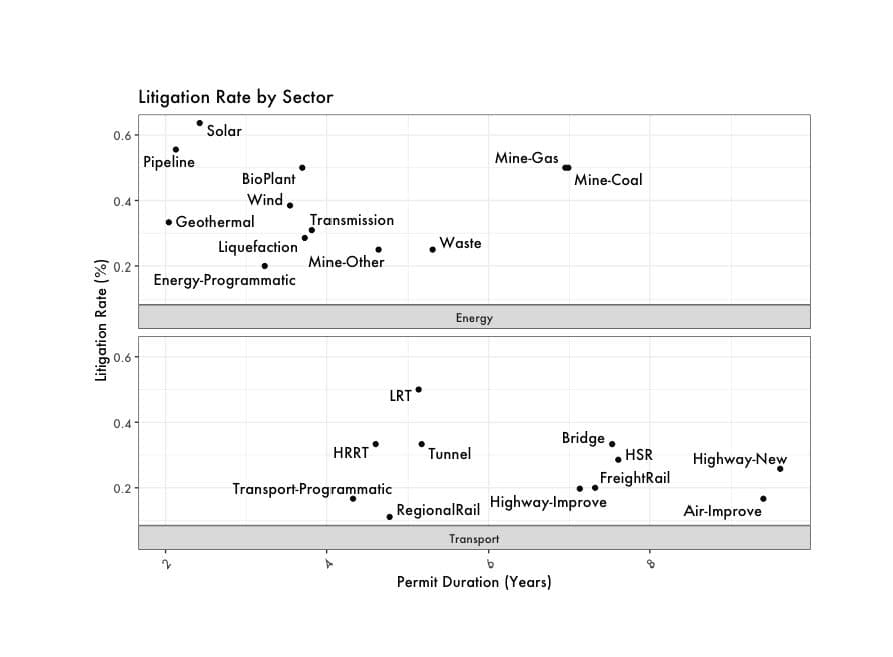

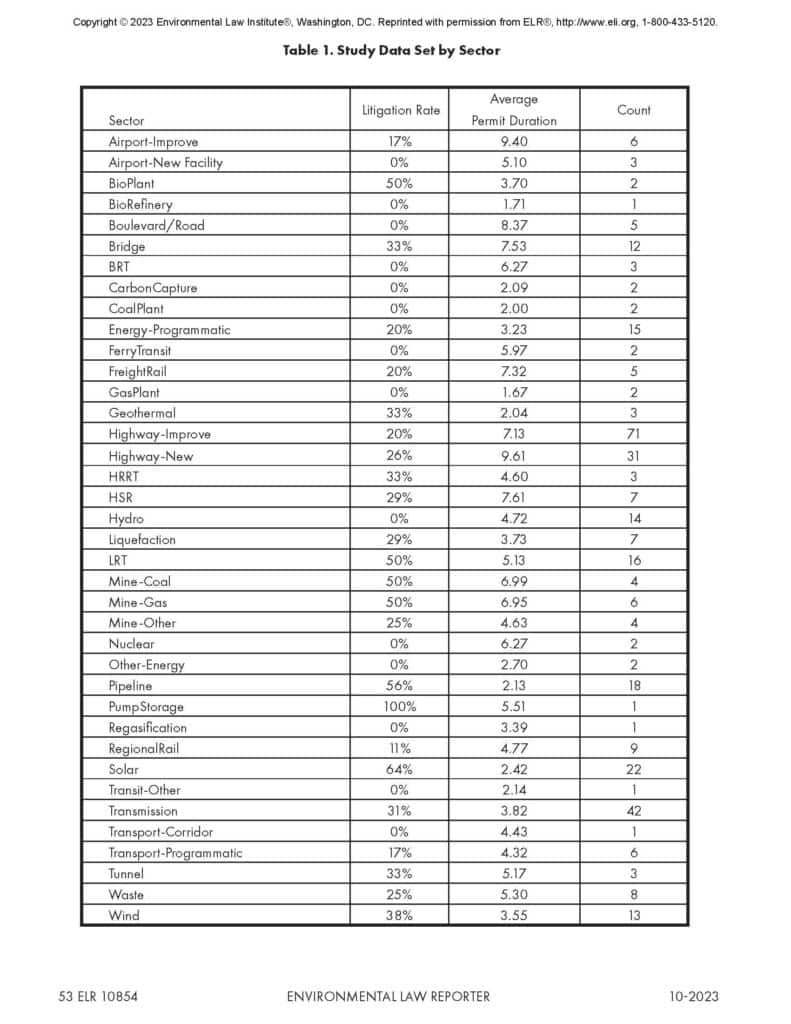

We observe predevelopment litigation on 28% of the projects requiring an environmental impact statement, 89% of which involve a claim of a NEPA violation. The highest litigation rate is in solar energy projects, nearly two-thirds of which are litigated. Other high-litigation sectors include pipelines (50%), transmission lines (31%), and wind energy projects (38%)

If anything, and at the highest possible level, we conclude that current debates regarding the question of permitting reform are overly focused on NEPA’s administrative process and comparatively neglect NEPA’s judicial process. Judicial review of NEPA appears to significantly impact infrastructure project development in the United States, and it impacts both the projects that are litigated

and those that are not.

Although the suthors are “happy to qualify that conclusion as limited to large infrastructure projects”, I think it is also relevant to forest management projects.

As discussed herein, many prior studies of NEPA practices and environmental litigation have focused on land management agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). We aimed tofocus specifically on infrastructure projects because they differ from area management or forestry projects in terms of both the impacts of the federal actions on the environment, and the practical impacts of environmental litigation on the projects.

One thing that’s obviously very different, and not in this quote, is the role of proponents. Let’s think about a fuel treatment project.. it is mostly between people who want it (including timber folks if there is a mill around) and people who don’t want it. For the most part, loggers and mills are not making investment decisions based on a specific project making it through the litigation mill. To the contrary, geothermal, solar and wind companies are subject to the whims of interest rates, the time value of money, supply chain difficulties and so on. Their operational environment is substantially more complex, and it appears that their connections to political actors may be stronger than, for example, Tina and her family who run Tina’s Sawmill. In the Forest Service, these projects may be more like Wolf Creek or ongoing litigated projects with specific proponents.

It is possible that NEPA’s architects, even Senator Jackson, failed to foresee28 the volume of litigation that would stem from the law because the environmental law sector was nascent, almost nonexistent, at the time of NEPA’s passing.

In fact, it is remarkable that NEPA’s evolution has been so primarily driven by case law rather than executive orders or major guidance by CEQ. After the 1978 CEQ guidance changes, NEPA did not undergo another major guidance change until CEQ published another revision in 2020, which was followed by additional rulemakings in 2021 and 2022.

In the case of NEPA, that limiting principle on the scope of environmental study is not found in law. NEPA’s “opaque, constitution-like language seems to give courts enough latitude to subject NEPA documents to either the hardest of looks or the softest of glances.”43 Judicial flexibility translates to agency uncertainty, to the point that permitting time and effort may be driven less by the anticipation of environmental impacts and more by the presence of conflict, or stakeholders with the resources and motivation to litigate against the project.44

The procedural nature of NEPA litigation is a key driver of “litigation proofing” and why contentious environmental studies under NEPA tend to grow into the many thousands of pages, despite the fact that strict page limits for EISs have been recommended by CEQ guidance since 1978. When asked to review NEPA studies, courts are deferential to federal agencies on their substantive determinations.46

On the question of limitations for its judicial reviews of agency NEPA decisions, the court in the Calvert Cliffs’ decision stated: “Although this inquiry into the facts is to be searching and careful, the ultimate standard of review is a narrow one. The court is not empowered to substitute its judgement for that of the agency.”

I keep reading that, but that’s not my lived experience. For example, I remember courts ruling that the BLM’s air quality model should not have been used; often courts weigh in on scientific controversies against the agency position. It’s entirely possible I’m missing something important and legal here, so maybe legal folks can enlighten me as to some kind of overall pattern in agency deference. Anyway…

They are far less deferential when considering topics, impacts, or alternatives that were not included in the environmental study. This dynamic can create a game of “cat and mouse” for project opponents and federal agencies, in which potential litigants try to identify and comment on alternatives or impacts that were not studied, and federal agencies are left to study everything as a means of litigation-proofing their environmental study.

Yes, cat and mouse, and sometimes it feels like judges “bring me a rock, no not that rock” to the agencies.

What the authors have to say about the “denominator” issue

Additionally, many prior studies have taken a very broad approach to estimating the prevalence of NEPA litigation. They do so by dividing the number of cases filed under NEPA (on average just over 100 annually) by the total number of agency actions that could be subject to NEPA litigation, which includes CEs and EAs (on the order of tens of thousands of actions). Most of those estimates rationally find that the litigation rates associated with NEPA are “exceedingly low.”130

Yet, we find such a calculation underwhelming, and especially so for our purpose, which is to study the impacts of the NEPA process on infrastructure development. The rate of NEPA litigation against all NEPA actions is less useful in part because the distribution of actions is extremely skewed. CEs constitute the vast majority of federal actions (upwards of 99%), and most of these permits are relatively short in duration for relatively minor actions.

This is an interesting observation.

We can generalize a bit and classify what we observe as two distinct but overlapping strategies for navigating federal environmental permitting: one that accepts a higher degree of litigation risk and thus has shorter permitting timelines but also higher rates of litigation, and another that has very long permitting timelines, perhaps due to litigation-proofing, and thus relatively lower rates of litigation. The question of which of these “strategies” is optimal would likely be determined by a wide range of unique circumstances of the environmental impacts, politics, and economics of a specific project.

However, we do note that in the sectors with higher rates of private investment in predevelopment, project sponsors appear to accept more permitting risk and to complete permits faster.

And something I’ve argued for:

The litigation databases that we used for this study are naturally oriented toward their users, or attorneys, and thus focused on published cases and legal precedent. Empirical research is much more challenging to conduct, especially in the many cases that do not result in a published opinion, or which are resolved via settlement. The result is a lack of transparency in many of the most important decisions regarding our public works and their mitigations, because many of those decisions are made during litigation settlement negotiations or during negotiations with stakeholders in the shadow of their threats of litigation.

It is in the public interest for transparency to be significantly increased in NEPA litigation and for other costs and litigation associated with the permitting of infrastructure projects. Recent legislative proposals have included transparency requirements addressing only minor, direct costs, such as the agency expenses to prepare an environmental study. A better alternative would be a requirement for federal agencies to publish online all documentation associated with project litigation during predevelopment, alongside the (already) publicly posted environmental study for the project. Given the public interest in project litigation, agencies should also be required to publicly disclose litigation documents instead of leaving journalists and the public to contend with and pay for federal court records.

Finally, here is their chart of kinds of projects they studied, litigation rate, average permit duration and counts.

Sharon said:

“I keep reading that, but that’s not my lived experience. For example, I remember courts ruling that the BLM’s air quality model should not have been used; often courts weigh in on scientific controversies against the agency position.”

===

Judges will not (and should not) typically substitute their own scientific judgment for that of the agency. However, they will examine the administrative record to ensure that the agency justified its scientific conclusions.

So, for example, a judge should not be rejecting BLM’s reliance on a particular air quality model simply because the judge believes the model is crappy or a better one is available. But the judge might remand an agency decision whose NEPA analysis relied on an air quality model based on conditions that differ from the project conditions.

For example, if in conducting an analysis of methane emissions for an o&g project in Wyoming, BLM uses a model constructed by analyzing methane emissions of cattle in Brazil, BLM will need to demonstrate in the record the work it performed to verify that model’s applicability to the Wyoming o&g project. [I’m making this one up – I’m sure there are better illustrations out there.]

There is some play in the joints here: some judges will demand a more thorough demonstration than others, but most judges are aware of their own scientific limitations and have no desire to clog their dockets by becoming scientific overseers of the agencies. I’m not saying there are no exceptions, but this is the general direction of travel.

Thanks, Rich! It is a very interesting area because there is a great deal of flexibility for judges to make judgments about … not whether the right model was chosen, but whether the agency wrote enough about why they picked that one versus another.

Agency used x science.

Plaintiffs say y science is better, and agency did not explain (adequately why they didn’t use y).

Plaintiffs say agency didn’t explain well enough why they used x.

So perhaps it’s not about the science per se but about the explanation. One paragraph, five pages, addressing every article every written…seems like there’s lots of play there.

There’s a lot here. This is a good insight: “Judicial flexibility translates to agency uncertainty, to the point that permitting time and effort may be driven less by the anticipation of environmental impacts and more by the presence of conflict, or stakeholders with the resources and motivation to litigate against the project.” Not that I necessarily think there is a LOT of judicial flexibility. I do think the main point is a reason why R1 has had a lot more litigation than say R4. A smart manager knows their plaintiffs. As for “anticipation of environmental impacts,” it doesn’t seem like you have lots of decision-makers saying they reject an alternative because it has too much of an effect on species x, which I do think was the intent behind NEPA.

But here’s what seems like a major oversight in this discussion. If the NEPA process for public participation is done properly (especially for EISs), the agency is going to know who is interested (and their litigiousness), what they are interested in, and, importantly what challenges are going to be made to the process – before litigation occurs. The agency should be able to assess the legal risk, and make an educated (informed by their legal counsel if it’s important enough) decision to revisit and possibly correct something procedural and/or substantive, or to accept the risk and move ahead. The APA judicial process, based on an administrative record, should preclude potential plaintiffs from surprising an agency with new issues. There should be no need for “explaining” or “litigation-proofing” issues that haven’t been brought up. The checkpoint after public review may take a little time in some cases, but I don’t see why this is operationally such a big problem.

Also, if, “project sponsors appear to accept more permitting risk and to complete permits faster” (with a higher risk of litigation), should we be surprised (or care much) if they get sued or lose?

I like Rich J’s reply regarding judicial deference. I used to refer people to this article (written by a Columbia Basin colleague from the BLM) for questions about deference to agency science. (I’m sure there’s new law, but it provides some principles for thinking about it.) I have a pdf I could share.

https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/vermenl10&div=14&id=&page=