‘Since I mentioned this in yesterday’s post, I thought I would post here. Here’s a direct way to pay people for ecosystem services.. which seems efficient. Plus there’s AI.. and local firms and people.

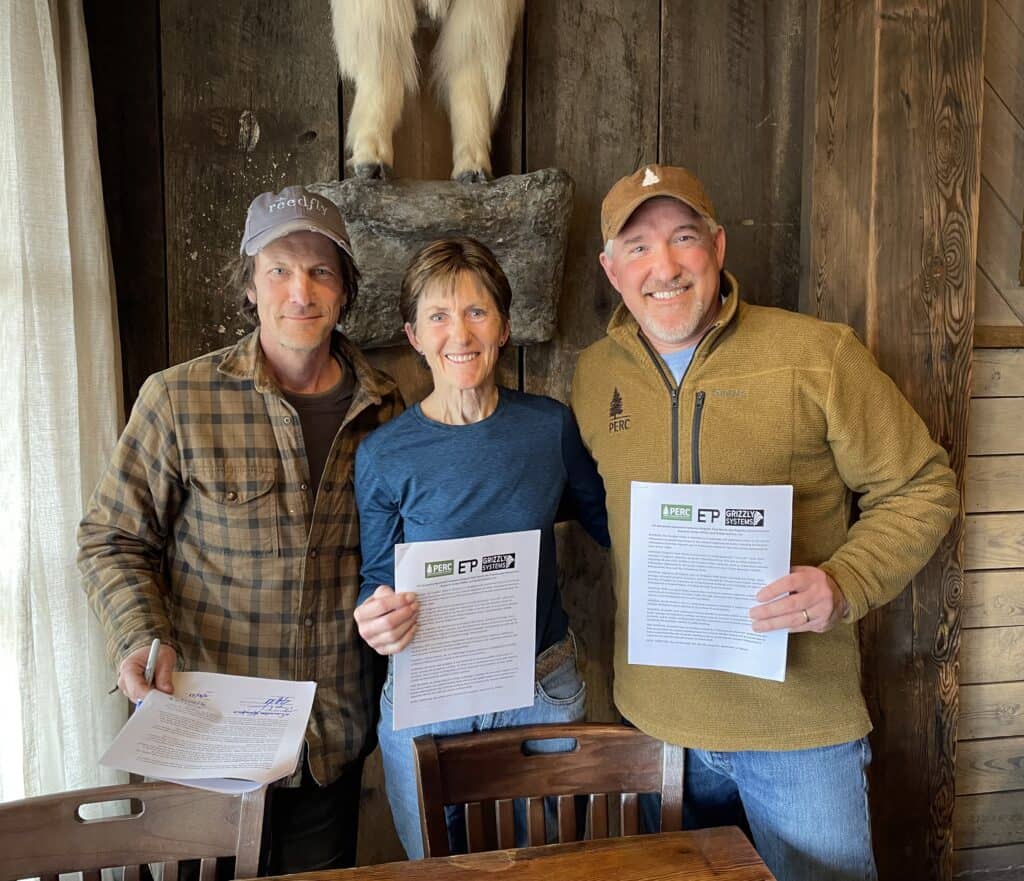

Paradise Valley, MT — The Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) today announced an innovative payment-for-presence program to compensate a rancher for providing elk habitat in Montana’s Paradise Valley.

Using advanced camera traps powered by artificial intelligence (AI) together with landowners’ innate knowledge of the land, this innovative program is the first of its kind in the region. Rather than paying ranchers for predator losses as traditional livestock compensation programs do, PERC’s payments are based on the presence of elk to specifically mitigate elk-livestock conflict.

Paradise Valley serves as an important wintering ground for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s migrating elk herds. As rapid development threatens wildlife habitat in the valley, ranchers and their large, open land holdings play a valuable role in maintaining ecosystem connectivity. Providing habitat, however, comes at a cost.

As the national leader in market solutions for conservation, Montana-based PERC works to develop incentive-based solutions that conserve wildlife habitat by helping mitigate those costs to landowners.

“Elk are often viewed as uninvited guests on a rancher’s property,” says PERC CEO Brian Yablonski. “Ranchers are essentially feeding the elk at great personal expense. Ultimately, we need these private open lands to remain intact if we want to conserve this unique migratory ecosystem, and paying ranchers ‘elk rent’ for providing this public good is a critical step toward accomplishing that.”

A minimum of 20 elk captured on camera across the ranch in a single day constitutes an “elk day” and triggers a financial payout to the rancher. A bonus payment is offered when 200 or more elk are captured in a single day, with a $12,000 cap on total annual payments.

Druska Kinkie, who along with her husband and son run Emigrant Peak Ranch, regularly sees 400-500 elk on her property during peak migration season. The heavy wildlife presence imposes costs through lost forage, fence damage, and the threat of disease transfer, namely brucellosis, a reproductive disease that is spread from elk and bison to cattle.

“This program has offered us a ray of hope,” said Druska Kinkie of Emigrant Peak Ranch. “We want to do right by the elk, but not at the expense of our livelihoods. Compensating their presence offsets the costs they impose, making the elk less of a liability for us.”

Harnessing smart cameras to calculate elk rent

The new program brings together Emigrant Peak Ranch and Grizzly Systems, a local technology firm that uses advanced AI camera traps with an integrated software platform. The advanced technology helps differentiate between random movement such as grass blowing in the wind and actual wildlife detection.

Harnessing smart cameras to calculate elk rent

The new program brings together Emigrant Peak Ranch and Grizzly Systems, a local technology firm that uses advanced AI camera traps with an integrated software platform. The advanced technology helps differentiate between random movement such as grass blowing in the wind and actual wildlife detection.

To try capturing the number of elk on the ranch at any given time, the program relies on game cameras installed in key locations throughout the property. Over time, the AI technology will learn how to better identify elk, reducing the amount of data to analyze. The rancher can also take photos with her smartphone to augment the game cameras.

The pilot program is designed to test the payment-for-presence system as well as the efficiency of artificial intelligence game cameras with continuous refinement.

“We’re excited to test the potential of our technology in such an important region for wildlife,” said Jeff Reed of Grizzly Systems. “We appreciate PERC’s spirit of creativity and flexibility to explore what makes the most sense for ranchers and wildlife. As our technology evolves, so too can the model of this program, delivering more tailored results.”

PERC’s Paradise Valley payment-for-presence program is the fourth project out of PERC’s Conservation Innovation Lab, including Montana’s first elk occupancy agreement, the Paradise Valley brucellosis compensation fund, and the grizzly grazing conflict reduction project in the Gravelly Range. When conservationists help ranchers offset the costs wildlife impose, they’re ultimately helping sustain the wildlife themselves.

Ranchers are instead uninvited guests into what has always been elk habitat. Courts have confirmed presence of wildlife goes with the land. Trying for another handout by entitled landowners. If they don’t want elk on their land, they need to open it up to lawful hunting.

I wondered about “who’s paying” until I got to this – “When conservationists help ranchers offset the costs wildlife impose.” I’m not sure who they are thinking of as “conservationists,” but it suggests those who benefit from the elk. So maybe we would increase hunting license fees? But how about those who benefit economically, like the businesses that make money off of hunters and tourists? It’s arguably a benefit to the general public, though, so maybe it should be financed by tax dollars (which I imagine PERC wouldn’t support). More broadly (and consistent with PERC’s philosophy) it suggests creation of a private property right that would disrupt the traditional relationship of the state to its wildlife.

I’ve actually seen some work like this being done to promote conservation of endangered species on private land (especially predators). These are species for which there is not currently the conservation funding infrastructure that exists for big game. It’s something that all kinds of conservationists should be willing to support.

https://www.thecgo.org/research/cameras-for-conservation-direct-compensation-as-motivation-for-living-with-wildlife/

I don’t see how paying for elk would “disrupt the traditional relationship of the state to its wildlife” but paying for predators would not. I must be missing something.

Predators that are listed under ESA (not game species). Paying for elk forage would move towards conceding that private landowners have a right to what the elk eat and should be compensated (as opposed to assuming the risk of losing it). Paying ranchers to feed elk is not unheard of, but it’s not a traditional state role (and you have to assume every rancher would expect payments).

But isn’t it simply a private agreement between willing landowners and willing donators? Actually Wyoming pays more for elk predation than for wolf. https://cowboystatedaily.com/2023/09/06/game-fish-reports-compensation-for-wildlife-damage-to-crops-nearly-equal-to-compensation-for-damages-to-livestock/

I’m not sure what property right you believe would be created or what you believe to be the traditional relationship of the state to its wildlife?

Regardless, leasing of private lands for wildlife habitat is a well established practice, at least in Oregon, where the first state wildlife refuges were comprised of leased private lands. That statutory authority still exists, although it’s, unfortunately and I believe failingly, rarely used in favor of fee title acquisition by the state.

In Oregon, most of the critical big game habitat is privately owned and, like most other states, private landowners reserve a constitutionally protected right to prevent injury to our private property from the state’s wildlife. The legal concept of ferae naturae doesn’t extinguish my right to protect my property any more than you living in a crime ridden neighborhood extinguishes your right to protect yourself from a home invasion burglar. I’ve argued for years that a service payment for big game habitat is a much better solution than paying for damage or living with depredation killing, if the state desires big game production. In fact, while doing research recently for a paper I’m writing on the history of mule deer in Oregon, I found published papers as far back as the early 1900’s declaring that if Oregon wanted to grow wildlife populations, particularly big game, that they would have to develop cooperative programs with private landowners since we owned most of the important habitats.

On a personal note, I have a forage budget for our ranch, where we provide substantial habitat for elk, mule and whitetail deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep while grazing cattle and reserving forage for watershed, soils, etc. My direct costs and foregone opportunity of housing the state’s wildlife is substantial and even though we enjoy and appreciate the animals, we certainly are looking at methods to commoditize them as much as our other economic endeavors.

The outdoor industry is a multi-billion annual economic sector and, in my experience, non-landowners frequently argue that landowners are the only ones who shouldn’t benefit from that economy even though, in many cases, we are the ones making the most significant, direct contribution to species conservation. That attitude strikes me as very bigoted and a total lack of comprehending basic monetization theory.

Under English common law, private landowners were under an obligation to support wildlife by retaining adequate forage and cover. Now states have the right to manage wildlife on private lands for the benefit of the public. There have been attempts to claim that state requirements of private landowners regarding wildlife amount to a Fifth Amendment “takings” of a private property right. I agree that as long as a payment for wildlife benefits by a state is voluntary there is no problem, but there are some who would like to construe that as an obligation.

Ahh. A Sax disciple. I should have figured.

And prior to English common law, as you know, Roman law. But just like the English common law of right of trespass that allowed unrestricted public access to uncultivated and unenclosed private “forest” land in the original 13 colonies for subsistence hunting, time and circumstance have eroded many of the early so-called public trust principles as they have other reserved rights such as a landowner’s right to kill any wild animal in trespass for any reason.

No matter how much the candlepackers and legal philosophizers dream about the PTD extending beyond tidal flats, navigable waterways and ocean beaches, it’s been my experience that the courts are reluctant to do so. Check out the Oregon supreme court decision in the Cherniak case where the State argued against it possessing either ownership or a public trust responsibility over anything but beaches, etc.; the court agreed.

A police power to prohibit actions by a landowner that substantially impairs a resource held for public benefit? Certainly. But I’m not aware of any “takings” or “rights” related decisions that concluded landowners had a requirement to take positive action on the behalf of wildlife. Please cite those cases for me as I’d be interested in reviewing them. Of course, looming over all of this is, for me and other property owners, the exciting possibility that another takings case winds up in front of this SCOTUS and, inarguably, a strong property rights protection majority. I’m particularly hopeful that it will have an ESA aspect although the Biden administration has been particularly devious in simply ignoring the decisions of the court and pressing forward anyway.

Regardless, what’s most troubling to me is that you and others apparently don’t understand or agree that incentivizing, rather than a centralized regulatory scheme, is of any value or that there is anything inherently wrong with making uncompensated demands of certain classes of citizens simply by virtue of their position. How would you react if the government demanded that you open up your residence to the homeless, forced you to provide for them and then restricted your ability to do anything about them once they started causing you problems?

I said nothing about the public trust doctrine, or “decisions that concluded landowners had a requirement to take positive action on the behalf of wildlife.” I am contemplating a claim by a landowner that the state owes them the value of the forage eaten by wildlife. The current state of wildlife law (which can’t really be compared to anything else) as I understand it, is that there is NOT “anything inherently wrong with making uncompensated demands of certain classes of citizens simply by virtue of their position.” (And I agree that if this made it to the current Supreme Court, any bizarre reinvention of property rights is plausible.)

You say “I said nothing about the public trust doctrine”…what you said previously was “[n]ow states have the right to manage wildlife on private lands for the benefit of the public”….that’s literally the definition of the public trust doctrine.

You say “I said nothing about…decisions that concluded landowners had a requirement to take positive action on the behalf of wildlife [quoting me]”…what you said previously was “[u]nder English common law, private landowners were under an obligation to support wildlife by retaining adequate forage and cover”. That seemed to me like you were claiming that landowners have an affirmative obligation, rather than a prohibitive one. My apologies for misinterpreting your claim.

Certainly, I agree with your statement regarding compensable “takings”, particularly in light of the multiple court cases dispensing with the issue, even while I disagree with the courts’ analysis. What I do not understand is why you would characterize a reversal as a “bizarre reinvention”. You would certainly acknowledge that the courts have evolved their thinking on other rights, why not property rights, particularly in light of contemporary legal scholarship that is generally in agreement that SCOTUS has not dealt with property rights as extensively as they have with others (mostly because they continue to push decisions back to the states for interpretation). Additionally, the courts have rarely dealt with the “injury” component of the takings clauses that exist in over 1/2 of state constitutions.

The analogy to me is if the state ordered homeowners to begin housing every city’s homeless population in their private residences, with restrictions on what you could do to protect your family and property. Every homeowner would howl like mashed monkeys and demand recompense. I understand that. Why would anyone expect landowners to act any differently?

To answer your last question, because there is an entirely different history. In light of that, a court that would “evolve” its thinking to change wildlife property rights would have to be considered pretty “activist” (if you don’t like “bizarre reinvention”). But this is a public lands blog, and while I have followed takings jurisprudence over the years, I don’t think I have a lot more value to add here.

Hi. Does this work for farm land, not just livestock land?

I think Wyoming pays farmers for wildlife eating farm fields, don’t know about other states; check this out.