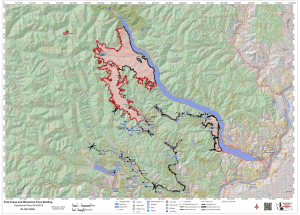

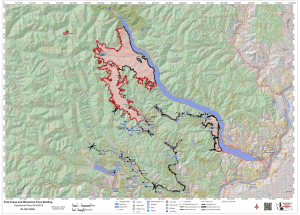

Today’s Seattle Times reports on a 5 million board foot timber sale conceived and consummated as a part of fighting the Wolverine Fire near Lake Chelan in Washington State. The sale, which cut a 50-mile long, 300-foot wide “community protection line” through spotted owl critical habitat and over streams, was logged primarily after rain had stopped the fire’s advance 8 miles from the Lake Wenatchee and Plains communities it was intended to protect. Contemporaneous Forest Service and FWS employees’ objections to the logging were overridden by the Wenatchee River district ranger.

Under normal circumstances, the National Environmental Policy Act would have required the Forest Service to assess this logging in an EA or EIS. But, Forest Service rules include an exception to NEPA analysis “[w]hen the responsible official determines that an emergency exists” and the actions are “urgently needed to mitigate harm to life, property, or important natural or cultural resources.” 36 CFR 220.4(b). In this instance, there is no written record of that determination having been made by “the responsible official,” or anyone else, for that matter. That’s the norm for Forest Service firefighting, which seeks to fly under NEPA’s radar using this regulation without ever following the regulation’s own terms itself. To the best of my knowledge, at no time does a Forest Service responsible official document that “an emergency exists” and that a particular action is “urgently needed.”

In the Wolverine Fire, the Forest Service’s behavior and facts on the ground belied any urgency to log this timber. If an urgent need to protect life or property had existed, the Forest Service would have warned the Lake Wenatchee and Plain communities to be prepared to evacuate. There are three levels of evacuation alert – Level 1 (Be Ready), Level 2 (Leave Soon) and Level 3 (Leave Immediately). At no time did the Forest Service put these communities on even the lowest level (Be Ready) evacuation alert. In contrast, Holden Village and Lucerne, which the Wolverine Fire actually threatened, received evacuation alerts and were evacuated.

When a wildfire threatens national forest visitors, the Forest Service also closes the area to public visitation. But here, when logging began, the Forest Service began relaxing public closures in the Wolverine Fire area, including reopening the Pacific Crest Trail to hikers.

Unaddressed in the news article is whether this 50-mile fuel break would have prevented the fire from spotting over the line. Had weather conditions been such that Lake Wenatchee or other communities actually been threatened (which they were not), it’s a fair bet that the fire could have jumped the line readily. In fact, the Forest Service warned that the Wolverine Fire might even jump Lake Chelan, which is a lot wider and less flammable!