Gov. John Hickenlooper’s wildfire team unveiled an overhaul of how Colorado deals with the growing problem of people building houses in forests prone to burn, shifting more of the responsibility to homeowners.

The overhaul recommends that lawmakers charge fees on homes built in woods, rate the wildfire risk of the 556,000 houses already built in burn zones on a 1-10 scale and inform insurers, and establish a state building code for use of fire-resistant materials and defensible space.

Sellers of homes would have to disclose wildfire risks, just as they must disclose flood risks. And state health officials would adjust air-quality permit rules to give greater flexibility for conducting controlled burns in overly dense forests to reduce the risk of ruinous superfires….

Protecting homes from wildfires is increasingly costly, with the state’s share going up from around $10 million a year to $48 million in 2012 and $54 million this year – some of which may be reimbursed by the federal government.

Yet construction in the mountains and foothills is accelerating. A Colorado State University study found development will cover 2.1 million acres in wildfire-prone areas by 2030, up from about 1 million today.

But parts of the plan face opposition from developers and the real estate industry.

“When you put a number 10 on a house, it can change the game. In a lot of cases, it could make property un-sellable,” said Colorado Association of Home Builders chief Amie Mayhew, a task force member.

Under the risk ratings recommendation, a home classified as high-risk would go through a “mitigation audit” to specify how to protect it against wildfire. Homeowners who do so could have their risk ratings reduced, said Barbara Kelley, director of the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, who ran the task force.”Homeowners in the wildland-urban interface should take on more of the responsibility” for protecting against wildfire, Kelley said.

Developers and the real estate industry also oppose a state building code unless implementation and enforcement is left up to local authorities.

And the Colorado Association of Realtors – not represented on the task force – rejects requiring disclosure of wildfire risks before home sales, vice president Rachel Nance said. House contracts could simply include a website address where buyers could conduct their own research into risks, she said.

Matthew Koehler

Tour Red Shale Wildfire in the Bob Marshall Wilderness

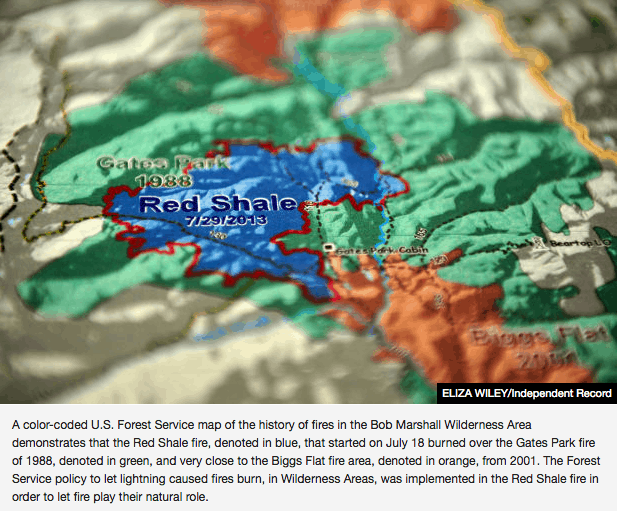

The Great Falls Tribune and Helena Independent Record recently teamed up (whether they knew it or not) to present a fairly cool multi-media education about the Forest Service’s “let it burn” policy as it applies to the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex and this summer’s Red Shale wildfire.

Not surprisingly, the Forest Service is finding that following nearly 30 years of following such a policy in the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex, fuels have been reduced, wildlife habitat has been created and US taxpayers have enjoyed significant wildfire suppression cost savings (again, whether they know it or not).

First, I highly recommend watching this short video from the Great Falls Tribune. Mike Munoz, Rocky Mountain District Forest Ranger on the Lewis and Clark National Forest is interviewed and gives some of the recent wildfire history in the Bob Marshall, as well as some of the rationale and justifications for the Forest Service’s “let it burn” policy. The video includes some pretty cool GoPro footage from high about the Bob Marshall, so enjoy some of those images.

Next, Eve Byron of the Helena Independent Record has a more extensive story, parts of which are highlighted below.

Twenty-five years ago this month, the Canyon Creek fire roared out of the Scapegoat Wilderness after slowly burning unfettered for more than three months, deep within the mountains, under part of the so-called “let it burn” U.S. Forest Service policy.

Eventually, the Canyon Creek fire burned across more than one-quarter of a million acres, forced the deployment of shelters by more than 100 firefighters and threatened the town of Augusta.

The local firestorm of criticism over the Forest Service’s handling of the Canyon Creek fire lasted even longer than the conflagration. But valuable lessons were learned, and this summer, as the Red Shale fire was allowed to burn relatively unchecked through the wilderness, it did so with little fanfare.

Brad McBratney, the fire staff officer for the Helena and Lewis and Clark national forests, and Rocky Mountain District Ranger Mike Munoz smile at questions about various firefighting tactics used by the Forest Service, well aware that the public typically has a limited understanding of how decisions are made as to whether to try to extinguish wildfires in wilderness areas or let them burn. They pull out two yellowed documents from the early 1980s, which foresters have used in the ensuing decades to put policies into practice on the ground, and half a dozen maps showing how fires have shaped the 1.5 million-acre Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex landscape since then.

“In 32 years, we have seen some significant fire activity on the landscape,” Munoz said….

McBratney and Munoz point toward this summer’s Red Shale fire as a textbook example of fire management, even though it is still burning after being started by lightning on July 18, about 35 miles west of Choteau. The fire has spread over 12,380 acres in a typical mosaic pattern, burning trees in one area but leaving others standing. Most of the burned area is within the footprint of the Gates Park fire, which ended up totaling about 52,000 acres.

They do more up-front planning, which includes examining various long-term scenarios. They get daily briefings on weather. More resources are in place — both people and equipment — if it’s needed. They map using satellites and infra-red radars. The develop models on where the fire is expected to burn and revisit those models regularly to tweak them.

Public information officers posted daily updates on a fire’s size, location and the number of resources assigned to it in Choteau and Augusta. There’s even an “app” that allows cell phones to scan it and go directly to the online “InciWeb,” a national incident management website that posts fire information, to learn more about the Red Shale fire.

Even if they’re not actively trying to extinguish the flames, they still use helicopters to drop water to cool the blaze and try to direct it away from some areas. They’ve wrapped historic cabins with fire-resistant materials and installed sprinklers as protective measures.

At the height of the Red Shale fire, about 25 people were assigned to it, including about 10 people on the ground. Today, four people are watching the fire, which is mainly smoldering after recent rains and cooler fall temperatures.

Today, after 100-plus fires in the Bob Marshall Complex have burned hundreds of thousands of acres since 1980, there’s less fuel to add to the fires. Munoz points to the Red Shale fire map, which shows how it burned to the edge of the 2001 Biggs Flat fire, then stopped without human intervention.

In addition to the natural fires within the wilderness area, forest officials have used prescribed burns to remove fuels outside the boundaries, with the hope that will make it easier to catch a fire that makes a run toward private property.

They’ve also worked on building relationships with local and state firefighters. McBratney is a member of the Augusta volunteer fire department, and Stiger said that during the recent fire season local volunteers meet weekly with state and federal representatives to talk about potential issues.

Study: Is fire severity increasing in the Sierra Nevada?

A new study published in the International Journal of Wildland Fire found that, contrary to what has been claimed in some of the news coverage of recent forest fires, there is not a trend toward increasing fire severity in the Sierra Nevada. Previously, those who claimed that fire severity was increasing relied primarily on two publications by Jay Miller of the Forest Service (Miller et. al 2009, Miller and Stafford 2012).

However, Dr. Chad Hanson and Dr. Dennis Odion found that the Miller studies left out hundreds of thousands of acres of fire data from their analysis. In contrast, Hanson and Odion used all of the available fire severity data for the Sierra Nevada, and that data showed no trend toward increasing fire severity.

Furthermore, they found that rate of high severity fire since 1984 has been lower than it was historically. These results refute some of the main claims we see on this blog and elsewhere.

Abstract

Research in the Sierra Nevada range of California, USA, has provided conflicting results about current trends of high-severity fire. Previous studies have used only a portion of available fire severity data, or considered only a portion of the Sierra Nevada. Our goal was to investigate whether a trend in fire severity is occurring in Sierra Nevada conifer forests currently, using satellite imagery. We analysed all available fire severity data, 1984–2010, over the whole ecoregion and found no trend in proportion, area or patch size of high-severity fire. The rate of high-severity fire has been lower since 1984 than the estimated historical rate. Responses of fire behaviour to climate change and fire suppression may be more complex than assumed. A better understanding of spatiotemporal patterns in fire regimes is needed to predict future fire regimes and their biological effects. Mechanisms underlying the lack of an expected climate- and time since fire-related trend in high-severity fire need to be identified to help calibrate projections of future fire. The effects of climate change on high-severity fire extent may remain small compared with fire suppression. Management could shift from a focus on reducing extent or severity of fire in wildlands to protecting human communities from fire.

White House threatens veto on Hastings/Daines mandated logging bill

The so-called “Restoring Healthy Forests for Healthy Communities Act” (H.R. 1526), which reads more like a timber industry/Sage Brush Rebellion wish list than anything else, is scheduled to be voted on by the US House sometime this week. (See Andy Stahl’s previous post for some vote-count predictions, as well as more information).

Of course, here in Montana it’s crystal clear that the Rep Daines/Hastings mandated logging bill is taken directly out of Senator Tester’s own mandated logging playbook.

Yesterday, the White House released a Statement of Administration Policy, which strongly opposed the bill and promised a veto:

“The Administration strongly opposes H.R. 1526, which includes numerous harmful provisions that impair Federal management of federally-owned lands and undermine many important existing public land and environmental laws, rules, and processes. The bill would significantly harm sound long-term management of these Federal lands for continued productivity and economic benefit as well as for the long-term health of the wildlife and ecological values sustained by these holdings. H.R. 1526, which includes unreasonable restrictions on certain Federal agency actions, would negatively impact the effective U.S. stewardship of Federal lands and natural resources, undertaken on behalf of all Americans. The bill also would create conflicts with existing statutory requirements that could generate substantial and complex litigation.” (See below for entire Statement)

I should mention that the White House’s Statement of Administration Policy on the “Restoring Healthy Forests for Healthy Communities Act” (H.R. 1526) has also been making the rounds via email among the Forest Service’s top communication’s strategists.

To date, none of the Tester mandated logging bill collaborators at the Montana Wilderness Association, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Montana Wildlife Federation, National Wildlife Federation or Montana Trout Unlimited have uttered one peep of resistance, protest or concern about the Rep Daines/Rep Hastings mandated logging bill, which the White House says would “undermine many important existing public land and environmental laws, rules, and processes.”

Instead these collaborators continue to court Rep Daines with expensive advertising and letters to the editor pressuring Daines to support Tester’s version of a mandated National Forest logging bill.

Yep, things are that whacky here in Montana.

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20503

September 18, 2013

STATEMENT OF ADMINISTRATION POLICY

H.R. 1526 – Restoring Healthy Forests for Healthy Communities Act

(Rep. Hastings, R-WA, and 22 cosponsors)

While supportive of working with States and communities to restore National Forests and rangeland, the Administration strongly opposes H.R. 1526, which includes numerous harmful provisions that impair Federal management of federally-owned lands and undermine many important existing public land and environmental laws, rules, and processes. The bill would significantly harm sound long-term management of these Federal lands for continued productivity and economic benefit as well as for the long-term health of the wildlife and ecological values sustained by these holdings. H.R. 1526, which includes unreasonable restrictions on certain Federal agency actions, would negatively impact the effective U.S. stewardship of Federal lands and natural resources, undertaken on behalf of all Americans. The bill also would create conflicts with existing statutory requirements that could generate substantial and complex litigation. A number of the Administration’s concerns with H.R. 1526 are outlined below.

Title I would negatively impact forest resources and the Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) current statutory obligations to manage forest lands by requiring USDA to sell no less than 50 percent of the sustained yield from the bill’s newly created Forest Reserve Revenue Areas (FRRA). The Administration does not support specifying timber harvest levels in statute, which does not take into account public input, environmental analyses, multiple use management or ecosystem changes. The bill would create a fiduciary responsibility to beneficiary counties to manage FRRAs to satisfy the annual volume requirement, which may create significant financial liability for the United States. It would also impede National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance for projects within FRRA, which undermines the reasoned consideration of the environmental effects of Federal agency actions. The bill also would establish significant barriers to the courts by imposing a requirement that plaintiffs post a bond for the Federal government’s costs, expenses, and attorneys’ fees.

Title II would give States the ability to determine management on Federal lands, including prioritized management treatments for hazardous fuel reductions and forest health projects without consultation with Federal land agencies, public involvement, or consideration of sound science and management options. The title would also accelerate commercial grazing and timber harvests without appropriate environmental review and public involvement, and would impede compliance with NEPA and Endangered Species Act (ESA) requirements. The Administration supports early public participation in Federal land management. The bill would mandate processes that shortchange collaboration and would lead to more conflict and delay. Further, this title’s mandated use of limited budgetary resources would likely reduce funding for other critical projects.

Title III would transfer from Federal agencies to a State-appointed Trust, the rights and responsibilities to manage most lands covered by the Oregon and California Railroad and Coos Bay Wagon Road Grant Lands Act (O&C) lands, and attempts to create exemptions from NEPA, ESA and other land management statutes. This would undermine appropriate management and stewardship of these lands, which belong to all Americans, would compromises habitat for threatened and endangered species, and would create legal uncertainty over management of these lands as well as increase litigation risk. Further, Title III also contains seriously objectionable limitations on the President’s existing authority under the Antiquities Act to designate new National Monuments in this region.

Title IV would remove authority from the Secretary of Agriculture for management of National Forest lands designated as Community Forest Demonstration Areas, while requiring the Secretary to be responsible for a number of management actions including fire presuppression, suppression, and rehabilitation. This title’s proposed management strategies would create a patchwork of management schemes and difficulties for the agency to meet other statutory and regulatory requirements. Federal environmental laws should apply on Federal lands; however, Title IV creates exceptions to, and potentially exemptions from the normal application of these laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, and the ESA.

If H.R. 1526 were presented to the President, his senior advisors would recommend that he veto the bill.

——————-

Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate HR 1526 “Restoring Healthy Forests for Healthy Communities Act”

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/hr1526.pdf

Idaho Statesman: Wildfires snare even managed areas

You can read Rocky Barker’s entire article here. Below are some highlights.

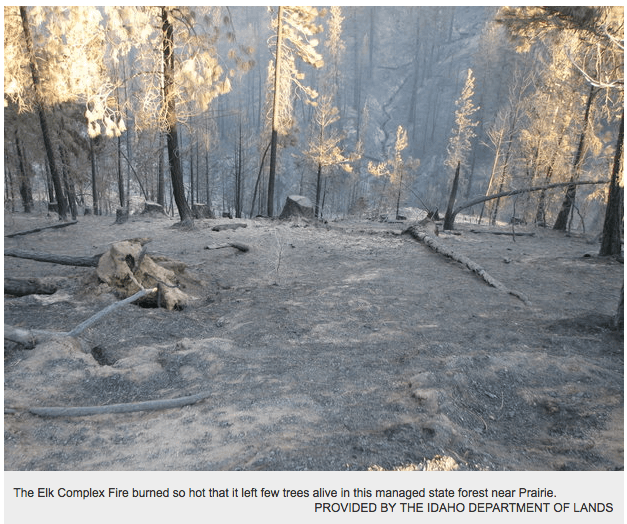

Emmett logger Tim Brown had just completed the White Flat timber sale on the Boise National Forest near Prairie when the Elk Complex Fire burned through in early August, destroying most of the remaining trees.

“That timber sale completely burned up,” said Dave Olson, a Boise National Forest spokesman.

The same happened on state lands nearby.

With extremely dry conditions and 50-mph winds, the fire burned so intensely that even the 6,000 acres of intensively managed state endowment forests burned, said Idaho Department of Lands Director Tom Schultz.

“There is little that land managers can do to prevent that kind of intense fire behavior,” said Schultz, who holds a master’s degree in forestry.

Presidential Proclamation: September is National Wilderness Month

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

A PROCLAMATION

In September 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law, recognizing places “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Throughout our history, countless people have passed through America’s most treasured landscapes, leaving their beauty unmarred. This month, we uphold that proud tradition and resolve that future generations will trek forest paths, navigate winding rivers, and scale rocky peaks as visitors to the majesty of our great outdoors.

My Administration is dedicated to preserving our Nation’s wild and scenic places. During my first year as President, I designated more than 2 million acres of wilderness and protected over 1,000 miles of rivers. Earlier this year, I established five new national monuments, and I signed legislation to redesignate California’s Pinnacles National Monument as Pinnacles National Park. To engage more Americans in conservation, I also launched the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative. Through this innovative effort, my Administration is working with communities from coast to coast to preserve our outdoor heritage, including our vast rural lands and remaining wild spaces.

As natural habitats for diverse wildlife; as destinations for family camping trips; and as venues for hiking, hunting, and fishing, America’s wilderness landscapes hold boundless opportunities to discover and explore. They provide immense value to our Nation — in shared experiences and as an integral part of our economy. Our iconic wilderness areas draw tourists from across the country and around the world, bolstering local businesses and supporting American jobs.

During National Wilderness Month, we reflect on the profound influence of the great outdoors on our lives and our national character, and we recommit to preserving them for generations to come.

NOW, THEREFORE, I, BARACK OBAMA, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim September 2013 as National Wilderness Month. I invite all Americans to visit and enjoy our wilderness areas, to learn about their vast history, and to aid in the protection of our precious national treasures.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this thirtieth day of August, in the year of our Lord two thousand thirteen, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and thirty-eighth.

BARACK OBAMA

Readers may also be interested in viewing this short video, American Wilderness, featuring National Park Service Wilderness areas.

5 Groups Appeal Tongass Timber Sale: 6,000 acres of old-growth would be logged, 46 miles of new roads constructed

The following was sent to me by the Greater Southeast Alaska Conservation Community (GSACC). If you have any questions about the release and the info contained within it, please contact the GSACC directly. Thanks. – mk

On August 16, GSACC and four other organizations filed an administrative appeal of the Tongass Forest Supervisor’s decision to proceed with the Big Thorne timber project. The appeal went to to the next highest level in the agency, Regional Forester Beth Pendleton. The appeal is known as Cascadia Wildlands et al. (2013), and other co-appellants are Greenpeace, Center for Biological Diversity and Tongass Conservation Society.

The project would log 148 million board feet of timber [enough to fill 29,600 log trucks], including over 6,000 acres of old-growth forest from heavily hammered Prince of Wales Island. 46 miles of new logging roads would be built and another 36 miles would be reconstructed. Our points of appeal encompass fundamental problems with the concept of the project, its economic problems, aquatic impacts from roading and logging, and severe impacts to wildlife including wolves, deer, bear, goshawks and flying squirrels. Our Request for Relief is that “the decision to approve the ROD and FEIS be reversed and that the project be cancelled in its entirety because of multiple failures to comply with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), National Forest Management Act (NFMA), Clean Water Act (CWA), Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA), Tongass Timber Reform Act (TTRA), Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) and various regulations and policies implementing these statutes.”

Included with the appeal were three expert declarations. One is by Dr. David Person, who did 22 years wolf and other ecological research on Prince of Wales Island and recently retired from the Alaska Department of Fish & Game. It says that the predator-prey system on the island (which includes wolves, bear, people and deer) is likely at the point of collapse, with the Big Thorne project being the tipping point. Another declaration is by Jon Rhodes, an expert on the sediment impacts of logging roads and their effect on fish. The third is by Joe Mehrkens, GSACC board member and former Alaska Regional Economist for the Forest Service, on the failings of the economic analysis in the Big Thorne EIS and economic nonsense this project embodies.

The appeal and the declarations are available for viewing and download at this link. Because the appeal is 127 pages, you will likely find the clickable table of contents useful. This series of e-mails illustrates the kind of biological knowledge that the State of Alaska has withheld from the NEPA process for the Big Thorne timber sale project on the Tongass National Forest.

Plum Creek Timber Co pays 25 cents/acre for annual firefighting fee assessment

Two weeks after the Lolo Creek Complex fire started, the Montana news media has finally let the public know that the vast majority of forest land burned in the fire is owned and managed by Plum Creek Timber Company, which just so happens to be the largest private landowner in the state.

Blog readers will recall that I was recently critical of the fact that no Montana media outlet apparently saw fit to mention even once or briefly that the Lolo Creek Complex fire was burning mainly on land owned and managed by Plum Creek Timber Company.

According to this morning’s Missoulian: “Most of the forest burned in the Lolo Creek Complex fire belonged to Plum Creek Timber Co., which hopes to recover what it can of the blackened trees this fall.”

Perhaps the most interesting part of the article was this bit of information about just how little Plum Creek Timber Company pays the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation for fighting wildfire on its private land:

Plum Creek also pays an annual firefighting fee assessment of about 25 cents an acre to the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation that works like insurance on all its approximately 900,000 acres of property in the state.

Montana State Forester Bob Harrington said the fee system is similar to programs used in most Rocky Mountain states to support firefighting efforts on private land. The money pays for equipment and training in years when fire activity doesn’t predominate the expenses.

Plum Creek also lost about 1,700 acres of timberland in the West Mullan fire near Superior in July. That area will also be assessed for possible salvage logging.

What do others think about the 25 cents per acre firefighting fee assessment? If it’s a fee assessment that works like insurance, then Plum Creek’s annual fee is approximately $225,000. Not a bad deal for insuring firefighting coverage over 900,000 acres of land, right?

Looked at another way, Plum Creek’s 7000 acres that burned in the 10,902 acre Lolo Complex Fire kicked in a grand total of $1,750 (7000 acres x 25 cents per acre) as per the firefighting fee assessment. I have yet to see concrete cost totals to the Forest Service, State DNRC and taxpayers for the Lolo Creek Complex fire but given the fact that this was the nation’s #1 priority wildfire recently and nearly 1,000 firefighters were fighting it at one point I’d have a hard time believing that total fire suppression costs would be anywhere south of $10 million.

Is this yet another real-world example of the timber industry getting one of the sweetest sweet-heart deals in America? Or does Plum Creek Timber Company (and other timber companies) paying about 25 cents per acre for a firefighting fee assessment pay their fair share of firefighting costs?

Hanson: The Ecological Importance of California’s Rim Fire

The following article, written by Dr. Chad Hanson, appeared yesterday at the Earth Island Journal. Once again, I’d like to respectfully request that if anyone has questions about the content of the article please contact Dr. Hanson directly. Thanks. – mk

The Ecological Importance of California’s Rim Fire: Large, intense fires have always been a natural part of fire regimes in Sierra Nevada forests

by Chad Hanson – August 28, 2013Since the Rim fire began in the central Sierra Nevada on August 17, there has been a steady stream of fearful, hyperbolic, and misinformed reporting in much of the media. The fire, which is currently 188,000 acres in size and covers portions of the Stanislaus National Forest and the northwestern corner of Yosemite National Park, has been consistently described as “catastrophic”, “destructive”, and “devastating.” One story featured a quote from a local man who said he expected “nothing to be left”. However, if we can, for a moment, set aside the fear, the panic, and the decades of misunderstanding about wildland fires in our forests, it turns out that the facts differ dramatically from the popular misconceptions. The Rim fire is a good thing for the health of the forest ecosystem. It is not devastation, or loss. It is ecological restoration.

What relatively few people in the general public understand at present is that large, intense fires have always been a natural part of fire regimes in Sierra Nevada forests. Patches of high-intensity fire, wherein most or all trees are killed, creates “snag forest habitat,” which is the rarest, and one of the most ecologically important, forest habitat types in the entire Sierra Nevada. Contrary to common myths, even when forest fires burn hottest, only a tiny proportion of the aboveground biomass is actually consumed (typically less than 3 percent). Habitat is not lost. Far from it. Instead, mature forest is transformed into “snag forest”, which is abundant in standing fire-killed trees, or “snags,” patches of native fire-following shrubs, downed logs, colorful flowers, and dense pockets of natural conifer regeneration.

This forest rejuvenation begins in the first spring after the fire. Native wood-boring beetles rapidly colonize burn areas, detecting the fires from dozens of miles away through infrared receptors that these species have evolved over millennia, in a long relationship with fire. The beetles bore under the bark of standing snags and lay their eggs, and the larvae feed and develop there. Woodpecker species, such as the rare and imperiled black-backed woodpecker (currently proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act), depend upon snag forest habitat and wood-boring beetles for survival.

One black-backed woodpecker eats about 13,500 beetle larvae every year — and that generally requires at least 100 to 200 standing dead trees per acre. Black-backed woodpeckers, which are naturally camouflaged against the charred bark of a fire-killed tree, are a keystone species, and they excavate a new nest cavity every year, even when they stay in the same territory. This creates homes for numerous secondary cavity-nesting species, like the mountain bluebird (and, occasionally, squirrels and even martens), that cannot excavate their own nest cavities. The native flowering shrubs that germinate after fire attract many species of flying insects, which provide food for flycatchers and bats; and the shrubs, new conifer growth, and downed logs provide excellent habitat for small mammals. This, in turn, attracts raptors, like the California spotted owl and northern goshawk, which nest and roost mainly in the low/moderate-intensity fire areas, or in adjacent unburned forest, but actively forage in the snag forest habitat patches created by high-intensity fire — a sort of “bedroom and kitchen” effect. Deer thrive on the new growth, black bears forage happily on the rich source of berries, grubs, and small mammals in snag forest habitat, and even rare carnivores like the Pacific fisher actively hunt for small mammals in this post-fire habitat.

In fact, every scientific study that has been conducted in large, intense fires in the Sierra Nevada has found that the big patches of snag forest habitat support levels of native biodiversity and total wildlife abundance that are equal to or (in most cases) higher than old-growth forest. This has been found in the Donner fire of 1960, the Manter and Storrie fires of 2000, the McNally fire of 2002, and the Moonlight fire of 2007, to name a few. Wildlife abundance in snag forest increases up to about 25 or 30 years after fire, and then declines as snag forest is replaced by a new stand of forest (increasing again, several decades later, after the new stand becomes old forest). The woodpeckers, like the black-backed woodpecker, thrive for 7 to 10 years after fire generally, and then must move on to find a new fire, as their beetle larvae prey begins to dwindle. Flycatchers and other birds increase after 10 years post-fire, and continue to increase for another two decades. Thus, snag forest habitat is ephemeral, and native biodiversity in the Sierra Nevada depends upon a constantly replenished supply of new fires.

It would surprise most people to learn that snag forest habitat is far rarer in the Sierra Nevada than old-growth forest. There are about 1.2 million acres of old-growth forest in the Sierra, but less than 400,000 acres of snag forest habitat, even after including the Rim fire to date. This is due to fire suppression, which has, over decades, substantially reduced the average annual amount of high-intensity fire relative to historic levels, according to multiple studies. Because of this, and the combined impact of extensive post-fire commercial logging on national forest lands and private lands, we have far less snag forest habitat now than we had in the early twentieth century, and before. This has put numerous wildlife species at risk. These are species that have evolved to depend upon the many habitat features in snag forest — habitat that cannot be created by any other means. Further, high-intensity fire is not increasing currently, according to most studies (and contrary to widespread assumptions), and our forests are getting wetter, not drier (according to every study that has empirically investigated this question), so we cannot afford to be cavalier and assume that there will be more fire in the future, despite fire suppression efforts. We will need to purposefully allow more fires to burn, especially in the more remote forests.

The black-backed woodpecker, for example, has been reduced to a mere several hundred pairs in the Sierra Nevada due to fire suppression, post-fire logging, and commercial thinning of forests, creating a significant risk of future extinction unless forest management policies change, and unless forest plans on our national forests include protections (which they currently do not). This species is a “management indicator species”, or bellwether, for the entire group of species associated with snag forest habitat. As the black-backed woodpecker goes, so too do many other species, including some that we probably don’t yet know are in trouble. The Rim fire has created valuable snag forest habitat in the area in which it was needed most in the Sierra Nevada: the western slope of the central portion of the range. Even the Forest Service’s own scientists have acknowledged that the levels of high-intensity fire in this area are unnaturally low, and need to be increased. In fact, the last moderately significant fires in this area occurred about a decade ago, and there was a substantial risk that a 200-mile gap in black-backed woodpeckers populations was about to develop, which is not a good sign from a conservation biology standpoint. The Rim fire has helped this situation, but we still have far too little snag forest habitat in the Sierra Nevada, and no protections from the ecological devastation of post-fire logging.

Recent scientific studies have caused scientists to substantially revise previous assumptions about historic fire regimes and forest structure. We now know that Sierra Nevada forests, including ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests, were not homogenously “open and parklike” with only low-intensity fire. Instead, many lines of evidence, and many published studies, show that these areas were often very dense, and were dominated by mixed-intensity fire, with high-intensity fire proportions ranging generally from 15 percent to more than 50 percent, depending upon the fire and area. Numerous historic sources, and reconstructions, document that large high-intensity fire patches did in fact occur prior to fire suppression and logging. Often these patches were hundreds of acres in size, and occasionally they were thousands — even tens of thousands — of acres. So, there is no ecological reason to fear or lament fires like the Rim fire, especially in an era of ongoing fire deficit.

Most fires, of course, are much smaller, and less intense than the Rim fire, including the other fires occurring this year. Over the past quarter-century fires in the Sierra Nevada have been dominated on average by low/moderate-intensity effects, including in the areas that have not burned in several decades. But, after decades of fear-inducing, taxpayer-subsidized, anti-fire propaganda from the US Forest Service, it is relatively easier for many to accept smaller, less intense fires, and more challenging to appreciate big fires like the Rim fire. However, if we are to manage forests for ecological integrity, and maintain the full range of native wildlife species on the landscape, it is a challenge that we must embrace.

Encouragingly, the previous assumption about a tension between the restoration of more fire in our forests and home protection has proven to be false. Every study that has investigated this issue has found that the only way to effectively protect homes is to reduce combustible brush in “defensible space” within 100 to 200 feet of individual homes. Current forest management policy on national forest lands, unfortunately, remains heavily focused not only on suppressing fires in remote wildlands far from homes, but also on intensive mechanical “thinning” projects — which typically involve the commercial removal of upwards of 80 percent of the trees, including mature trees and often old-growth trees —that are mostly a long distance from homes. This not only diverts scarce resources away from home protection, but also gives homeowners a false sense of security because a federal agency has implied, incorrectly, that they are now protected from fire — a context that puts homes further at risk.

The new scientific data is telling us that we need not fear fire in our forests. Fire is doing important and beneficial ecological work, and we need more of it, including the occasional large, intense fires. Nor do we need to balance home protection with the restoration of fire’s role in our forests. The two are not in conflict. We do, however, need to muster the courage to transcend our fears and outdated assumptions about fire. Our forest ecosystems will be better for it.

Chad Hanson, the director of the John Muir Project (JMP) of Earth Island Institute, has a Ph.D. in ecology from the University of California at Davis, and focuses his research on forest and fire ecology in the Sierra Nevada. He can be reached at [email protected], or visit JMP’s website at www.johnmuirproject.org for more information, and for citations to specific studies pertaining to the points made in this article.

2013 Fire Season in New Mexico Below Normal: Nearly 60% of forest land within fire boundaries remained unburned or burned at low severity

The following press release is from WildEarth Guardians. If you click on this link, you can see a few charts and a map. If anyone has questions about the information contained within this press release from WildEarth Guardians, please contact WildEarth Guardians directly. Thank you. – mk

2013 Fire Season in New Mexico Below Normal:

Nearly 60% of forest land within fire boundaries remained unburned or burned at low severity

Contact: Bryan Bird (505) 699-4719Santa Fe – New Mexico experienced several expensive fires early this summer, the largest was the Silver Fire covering nearly 217 square miles in the Black Range. Fire costs in the U.S. have topped $1 billion so far this year; less than last year’s $1.9 billion, but the fire season is not over. The Thompson Ridge fire alone cost $16,326,136 before it was declared contained. Rising plumes of smoke could be seen on the horizon of Santa Fe and Albuquerque and breathless reporters gave statistics of ever increasing acreages of devastated forestland.

But, the numbers tell a different story. The four major fires in New Mexico this summer covered a total of 184,024 acres or nearly 288 square miles, but just 16% of that area burned at high severity. In all 213,289 acres have burned to date in New Mexico. While there is still a chance for late season fires, the total burned area for 2013 is significantly less than the 372,497 acres burned in 2012.

“Once the smoke cleared, the environmental benefits of the 2013 fire season were obvious,” Said Bryan Bird, Wild Places Director for WildEarth Guardians. “Though flooding is always a risk, these fires do more to clear fuels and reduce fire hazard than we could do with mechanical treatments and a large chunk of the federal budget.”

Burn Area Emergency Response (BAER) teams take action immediately after fires to analyze the area within the burn perimeter and take action to minimize immediate damage from flooding, which can have severe consequences downstream. The BAER teams measure fire severity to analyze the loss of organic matter from the forest. In areas of low fire severity ground litter is charred or consumed, but tree canopies remain mostly unburned and the top layer of soil organic matter remains unharmed. Areas of moderate severity have a higher percentage of both crown and soil organic matter consumed. Areas of high severity have lost all or most of tree canopy organic matter and soil organic matter is wholly consumed.

The numbers reported by the BAER teams for the 2013 fire season in New Mexico put into perspective the burn results. Of all acres within fire boundaries over 10,000 acres this summer, 59% (109,290 acres) were ranked as unburned or low severity. Another 24% (44,880 acres) was moderate severity. Finally, just 16% (29,125 acres) burned at high severity.

The Joroso Fire, located in the Pecos Wilderness, burned primarily in mature Spruce Fir stands with high levels of wind blown material. These conditions create an environment where high severity burns are much more likely than the other fires, so it is instructive to remove it from summary statistics. When removing this fire from the analysis the overall numbers demonstrate even less severe effects on the vegetation: 61% remained unburned or burned at low intensity, 25% burned at moderate severity, and only 13% burned at high severity.

Fire fighting in the United Sates has become a very costly endeavor. While most fires are extinguished quickly, it is the very small portion of wildfires that are not immediately controlled and result in significant financial burdens to states and the federal government. Already this year the Forest Service has exhausted its fire-fighting budget and has had to tap other budget line items. And yet, it is not clear that committing such resources is necessary or beneficial when human life and property are not immediately at risk.

“Fire is an essential process in western forests and we cannot eliminate it. Resources need to be reserved for protecting lives, not supporting huge operations in the backcountry.” Said Bird. “We can fire proof communities, but we cannot fire proof the forest.”