Not even a pandemic can stop forest planning.

Forest plan revisions for the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon and Washington stalled again in March, 2019, when the Forest Service Washington Office responded to objections on the Umatilla, Malheur and Wallowa-Whitman revised forest plans by instructing the regional forester to withdraw the draft record of decision for “additional information.” One of the reason given was, “The Revised Plans also did not fully account for the unique social and economic needs of local communities in the area.” While not specifically citing these instructions, the Forest Service and the Eastern Oregon Counties Association have funded a research project that will help understand the impacts of forest management across the Blue Mountain region, including the potential impacts of new forest plans. The Forest Service has always done social and economic analysis as part of forest planning, but according to Nils Christoffersen, director of Wallowa Resources …

“The desire was to create a system to get more localized analysis of what would be the impact of increasing or decreasing timber harvest on national forest land, (or) increasing or decreasing the grazing activities,” he said. “(It’s) trying to understand the relative economic importance of the national forest system land and their management to the economics of the Eastern Oregon counties.”

The Manti-La Sal National Forest released a “draft forest plan” in October as part of its plan revision process. The Forest cautions that they are not even to formal the scoping stage, which would initiate the EIS process, but they are looking for public comments on what I would characterize as a detailed proposed action. They have scheduled several “virtual workshops” that address different plan revision topics. (After today, one remains on “Watershed,” December 3.) A coalition of conservation groups has already submitted a “conservation alternative” that, “emphasizes scientific data and recommends adapting forest use to climate change and population growth as well as prioritizing conservation of water, native species and ecosystems over commercial use, and pushing for greater inclusion of Indigenous groups in policy-making.”

In fiscal year 2020, the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest sold 84.5 million board feet of timber, the most since 1991. An annual volume of 125-150 million board feet is included in the current draft of the revised forest plan.

Environmental groups are split over the uptick. Some, like Gary Macfarlane of the Moscow-based Friends of the Clearwater, say it is damaging water quality and habitat for salmon and steelhead. While others, like Brad Smith of the Idaho Conservation League, say current logging levels appear sustainable as long as the work is done with proper environmental review and robust public participation. The latter has participated in the Clearwater Collaborative, while the former hasn’t.

“If they maintain the current riparian buffers, if they don’t harvest old growth and they provide adequate wildlife habitat security, I think 125 million board feet (per year) is sustainable,” Smith said.

The Forest Service proudly proclaims,

“The more volume we produce, the more miles of roads we maintain, the more sediment we reduce and the more fish passage culverts we install — and the more wildlife habitat gets improved.”

A county commissioner has reservations about this, since the programs allowing the agency to reinvest proceeds of timber harvest into restoration cut the county out of its share. (I have my own reservations about logging to raise money, especially if it is independent of ecological needs established in the forest plan, and how that is used in the NEPA process as discussed here.)

McFarlane doesn’t buy the agency’s contention that logging leads to improved environmental conditions.

“To conflate logging with restoration is one of the biggest hoaxes perpetrated on the American public,” he said. “There is no science that supports that — none.”

“They are always predicting an upward trend (in water quality) for all of the road decommissioning they are doing, but when they go back into the watershed (to monitor water quality) they are still not meeting forest plan objectives. That is why they want a new plan that removes those objectives.”

Nez Perce-Clearwater revision page

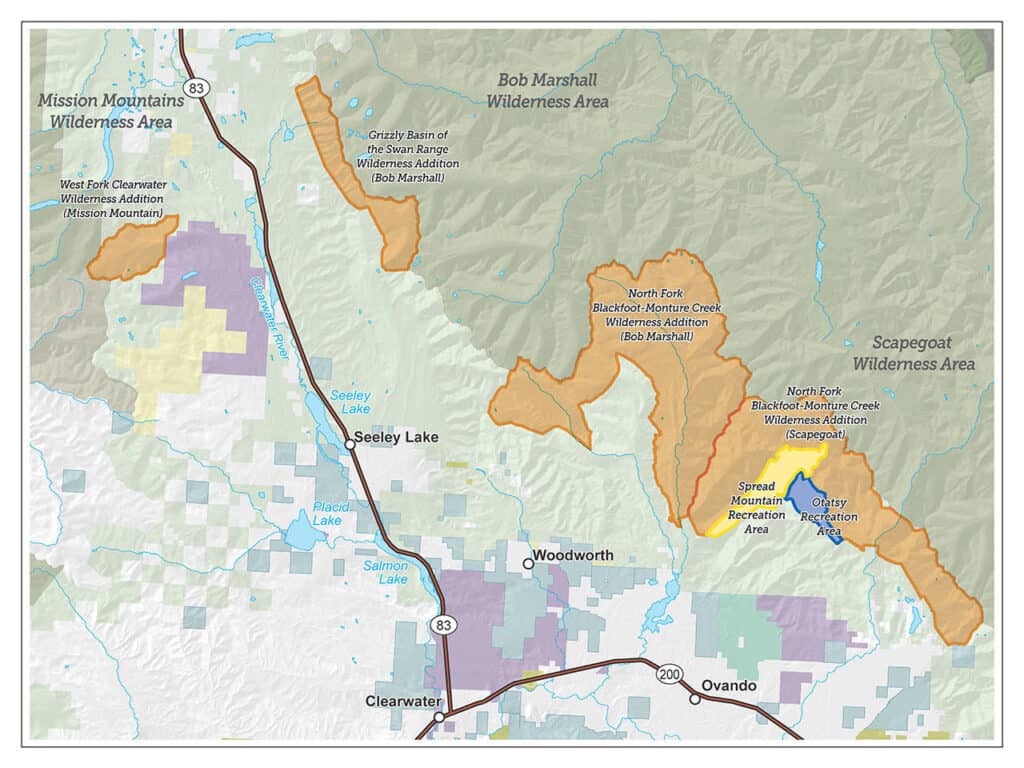

The Custer-Gallatin National Forest held its meeting with those who have objected to its final revised forest plan. The issues revolve mostly around wilderness designations. According to this article, most objectors argued the land designations proposed for these areas don’t sufficiently safeguard wildlife habitat from recreation-related fragmentation. The objectors include the Gallatin Forest Partnership, which submitted its own set of recommendations for the plan to the Forest Service. One of those recommendations for wilderness is supported by the Southwest Montana Mountain Bike Association.