Since the NFS litigation reporter is apparently furloughed, here is something you might not want to miss …

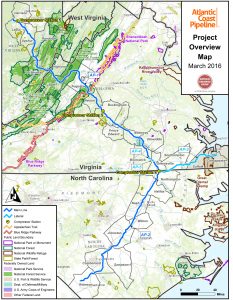

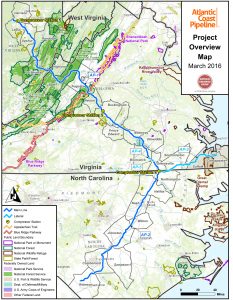

In July the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the Jefferson National Forest for improperly amending its forest plan to create an exception to forest plan standards to allow the construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline (reported here and discussed here). On December 13, the same court ruled against the George Washington and Monongahela National Forests for improperly amending their plans to create exceptions to 13 forest plan standards to allow the construction of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Cowpasture River Preservation Association v. Forest Service again involved interpreting a 2016 amendment to the Planning Rule that governs the application of the 2012 Rule to forest plan amendments. It also again involved circumstances where the Forest Service reversed itself regarding its concerns about the effects of a pipeline without justification.

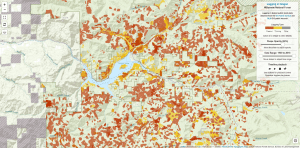

Forest plan amendments to existing plans (that were not prepared pursuant to the 2012 Planning Rule) are subject to the substantive requirements of the 2012 Planning Rule when those requirements are directly related to the amendment. This may occur when the requirements are related to either the purpose or effects of the amendment(in a “substantial” way). The Forest Service found that relevant effects on soil, water, riparian, threatened and endangered species, and recreational and visual resources were mitigated, but ignored the purpose of the amendment, which was (as stated in the NEPA documents) to reduce the protection of those resources so the Pipeline could proceed. As stated by the court, “To say that a 2012 Planning Rule requirement protecting water resources (as one example) is not “directly related” to a Forest Plan amendment specifically relaxing protection for water resources is nonsense.”

The court rejected the argument that it is the purpose of the project that should be considered rather than the purpose of the amendment, and rejected the idea that these requirements do not apply to amendments limited to an individual project. It found, “If the Forest Service could circumvent the requirements of the 2012 Planning Rule simply by passing project-specific amendments on an ad hoc basis, both the substantive requirements in the 2012 Planning Rule and the NFMA’s Forest Plan consistency requirement would be meaningless.” The court also suggested that there would be “substantial” adverse effects of this project that should lead to a conclusion that the amendments are “directly related,” and the 2012 Planning Rule requirements would apply. The court held: “The lengths to which the Forest Service apparently went to avoid applying the substantive protections of the 2012 Planning Rule — its own regulation intended to protect national forests — in order to accommodate the ACP project through national forest land on Atlantic’s timeline are striking, and inexplicable.”

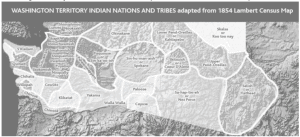

The court also found a violation of forest plan goals, “because it failed to demonstrate that the ACP project’s needs could not be reasonably met on non-national forest lands.” The FEIS did not address this question, but instead found that no national forest avoidance alternative “confers a significant environmental advantage over the proposed route.” The court held that consistency with plan goals is required by the 2012 Planning Rule (even though the goals were not written when that Rule was in effect). The Forest had included the goals (which are also found in the Forest Service Manual) in its scoping material for the Pipeline project. The court held that the Forest Service “is not free to disregard the goal entirely — as the Forest Service apparently wishes to do here.”

The court also found violations of NEPA. The EIS was prepared by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), but the Forest Service had duty to independently review it. The Forest Service never explained why it was satisfied with the lack of off-forest alternative routes after it had said they were required. The Forest Service also failed to explain why it lost interest in landslide risks, erosion control and aquatic species that it had previously expressed concerns about. The court found, “the record before us readily leads to the conclusion that the Forest Service’s approval of the project “was a preordained decision” and the Forest Service “‘reverse engineered’ the [ROD] to justify this outcome.”

The court remanded the Forest Service decisions to grant the right of way to address these legal shortcomings. However, the court also found a potentially bigger problem: the Forest Service does not have the authority to grant a right of way across the Appalachian National Scenic Trail (necessary for the routes considered) because it is administered by the National Park Service, and the Park Service does not have authority to grant such a right of way at all. Thus this part of the Trump Administration’s “energy dominance” program could now be in the hands of a divided Congress.

Here is the line from the court that got the most media attention (includes a link to the opinion):

“We trust the United States Forest Service to “speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues.” Dr. Seuss, The Lorax (1971). A thorough review of the record leads to the necessary conclusion that the Forest Service abdicated its responsibility to preserve national forest resources.”