And Trump says “tree clear.” This article got my attention for a number of reasons. It’s a follow-up to the story about the Trump tweet regarding forest fires. It is another case of “upping the cut” under the Trump administration (doubling in this case on the Los Padres). And it looks like the Forest is trying to disguise what it is actually doing with this project. And using a questionable categorical exclusion to boot.

Critics contend the proposed logging in the Los Padres is a signal that the balance of power in national forests is shifting under the Trump administration. Such projects could open the door to commercial logging in other public forests currently managed as watersheds rather than timberlands, such as the Angeles, San Bernardino and Cleveland national forests.

Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue raised annual timber production targets for the Los Padres National Forest from 200,000 cubic feet of wood in 2017 to 400,000 cubic feet this year.

“We are witnessing a historical change unfolding in the national forests in our own backyard,” said Richard Halsey, founder of the nonprofit Chaparral Institute in Escondido, Calif. “Timber was never part of the equation, until now.”

Here’s the way the article introduced the project:

The federal government is moving to allow commercial logging of healthy green pine trees for the first time in decades in the Los Padres National Forest north of Los Angeles, a tactic the U.S. Forest Services says will reduce fire risk.

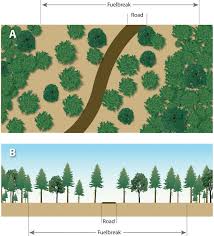

The scoping letter described the project as a “shaded fuelbreak.”

Treatments would include a combination of mechanical thinning, mastication of brush/smaller trees, and hand treatments such as hand thinning, brush cutting, pruning and piling of material.

That sounds fairly benign, but the proposed action sheds a little more light on it:

Mixed conifer and pinyon juniper stands would be thinned to a range of 40 to 60 square feet basal area per acre… Trees would be removed throughout all diameter classes and would include the removal of commercial trees. Residual trees would be selected for vigor; however, larger Jeffrey pine would be retained per Forest Plan direction unless they pose a hazard or are infected with dwarf mistletoe. All black oak would be left unless they pose a hazard.

But the scoping letter states an intent to use this categorical exclusion:

(6) Timber stand and/or wildlife habitat improvement activities that do not include the use of herbicides or do not require more than 1 mile of low standard road construction. Examples include, but are not limited to:

(i) Girdling trees to create snags;

(ii) Thinning or brush control to improve growth or to reduce fire hazard including the opening of an existing road to a dense timber stand;

(iii) Prescribed burning to control understory hardwoods in stands of southern pine; and

(iv) Prescribed burning to reduce natural fuel build-up and improve plant vigor.

And then there’s this:

Ashley McConnell, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said her agency plans to work with the Forest Service to help protect active California condor nest sites or roosting areas. Logging, she said, could “benefit California condor habitat because the larger and older trees where condors typically roost are preserved.”

That’s what “thinning” means, right?

So has it been so long since the Los Padres has had a timber sale that they don’t know what to call it? Or is this an attempt at sneaking by the NEPA requirements that go along with it? Maybe you can technically call it “thinning” if you leave any residual trees, but that is clearly not what this CE was intended to cover. There is another CE for hazardous fuel reduction, but it’s limited to 1000 acres of “mechanical treatments.” And another for “harvest of live trees” (limited to 70 acres). Is this the kind of misleading corner cutting the Forest Service is going to go back to when it is under pressure to “get the cut out?”