Sure enough, the FS doesn’t actually have a “can’t do” attitude as it appeared from my read of the recent hearing. From chatting further with Chris French, it turns out that they are well down the road with an innovative approach to deal with LMP revisions, and to actually get them back on schedule (!).

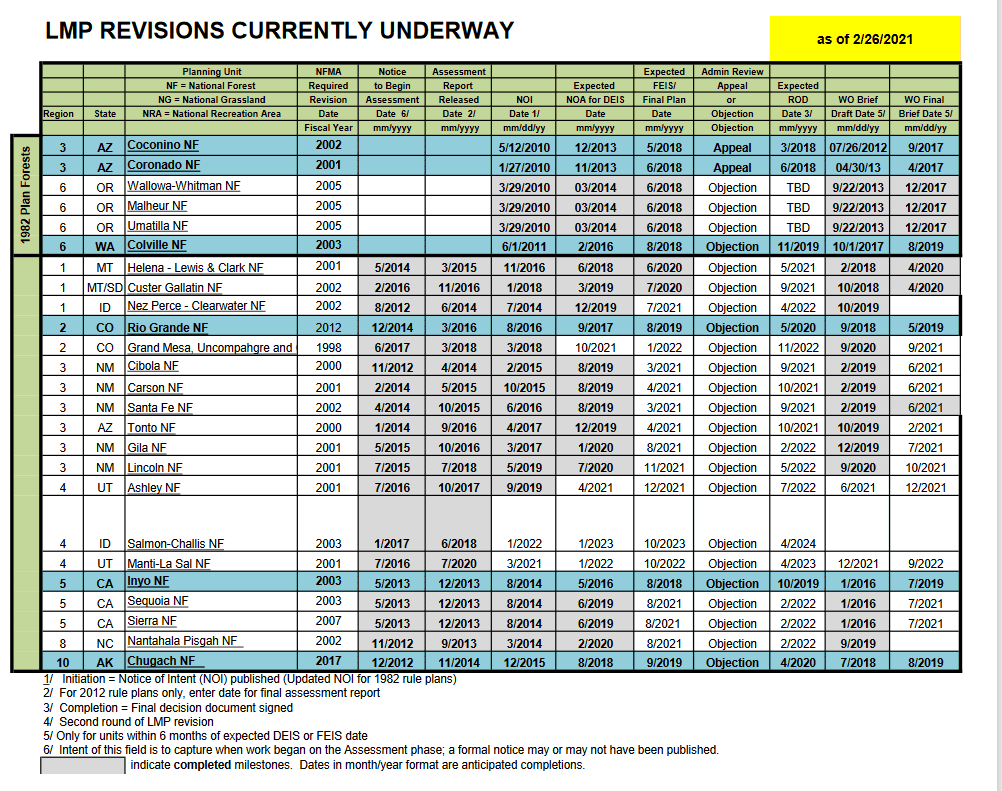

Sure enough, (this will not surprise anyone) the 2012 Rule is difficult and complex to do, and the FS decentralized approach makes for inconsistencies. We’ve observed those here at TSW. Despite the unduly optimistic Q&As from the 2012 Rule:

Under the 2012 planning rule the agency should be able to revise more plans with the same amount of money. The 2012 planning rule should reduce the amount of time (3-4 vs. 5-7 years) and the amount of money ($3-4 vs. $5-7 million) that it takes to revise individual forest and grassland land management plans, as compared to the current 1982 procedures.

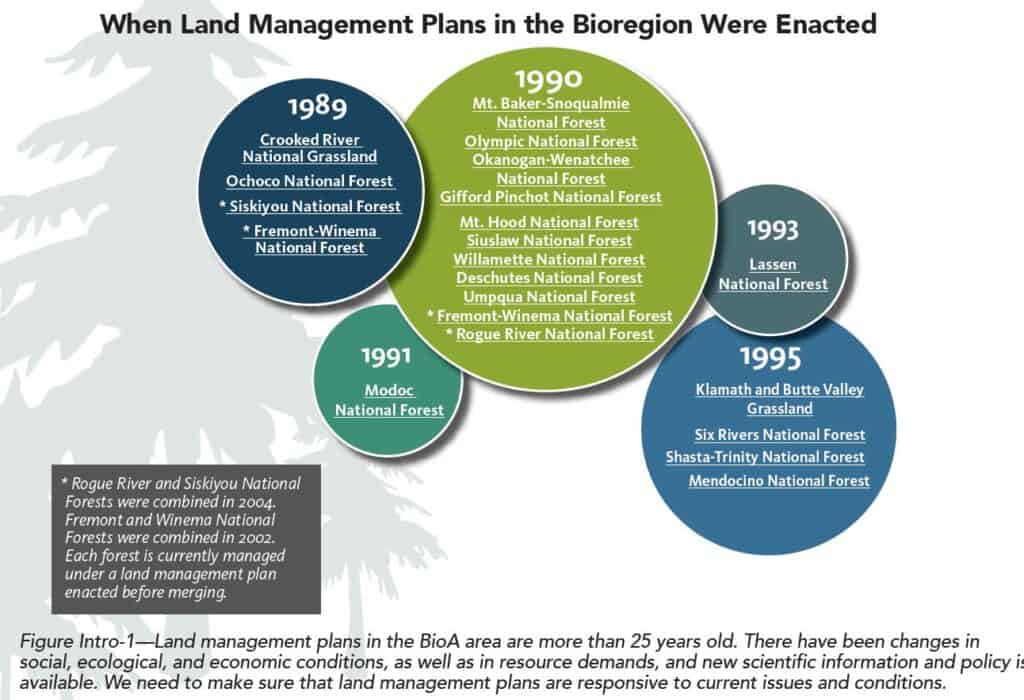

That’s not the way it’s worked out. Using simple logic, if you do more analysis and involve people more, it takes more time and costs more money. This seemed obvious to everyone at the time, apparently everyone but the people who did the PR for the Rule. So the reality has been more like 7-8 years. And the FS folks noticed that this was a problem, especially since the desired target of NFMA is a plan that is revised every 15 years. It makes sense for them to try something different, because next year will be 10 years since the 2012 Rule was published, and it is a reasonable time to assess how it has been working and to do some adaptive management.

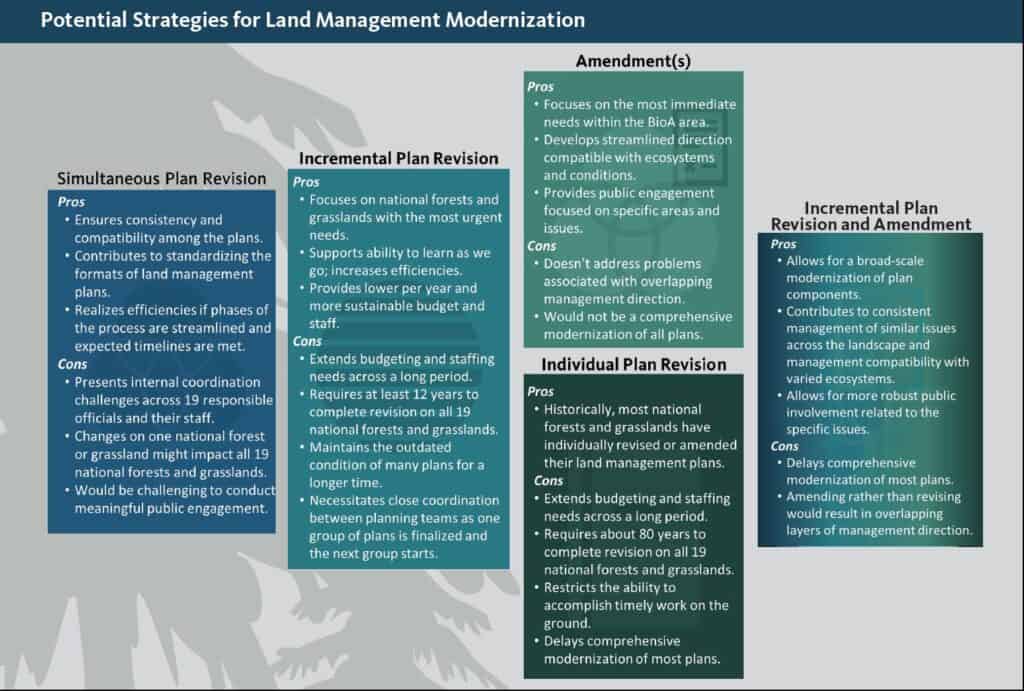

So to that end, the FS is in the process of figuring out the details of a new way to approach forest planning. It’s a hybrid model, with decision authority and stakeholder involvement remaining at the forest level, while analysis and other technical issues are provided in geographic teams that handle multiple revisions. There will also be some national teams or other efforts to ensure consistency. The idea is to be able to get on a national planning rotation of 10-15 years with an expected timeframe of 3-4 years per plan.

Chris also made clear that this hybrid model was developed prior to the current discussions on the Reconciliation bill, which as you may remember calls for (in October 28 version):

$350,000,000 for National Forest System land management planning and monitoring, prioritized on the assessment of watershed, ecological, and carbon conditions on National Forest System land and the revision and amendment of older land management plans that present opportunities to protect, maintain, restore, and monitor ecological integrity, ecological conditions for at-risk species, and carbon storage.

Chris noted that that this funding would indeed be helpful in getting plans done.

So stay tuned, and more information will be forthcoming on the details of the model when the Forest Service has the complete package finalized.

*************************

My view: this approach sounds eminently sensible to me. After all, decentralization is a philosophy, not a commandment. Some regions do some versions of this already, as I understand.

It also reminds me of the BLM RMP approach in Nevada that we looked at here and their rationales. If you do something once every twenty to thirty years, it’s unlikely you will get very good at it compared to those who do it all the time. And in the case of the 2012 Rule, if you’ve never done it, you’re probably not as good at using it as someone who has.

As a wonk, I would have preferred a more formal open process with public involvement in “what is working and what isn’t” after ten years of experience, including the views of stakeholders, scientists, and so on, who actually have been involved in the guts of a revision process. It would include the possibility of tweaks to the Rule itself. Like an LMP, doing a new rule is opening Pandora’s box, whereas specific amendments can be very helpful based on the concept of a “need for change.”

Side note: If the FS chose to prioritize fire amendments instead of revisions (OK, which seems unlikely, still..), the bill language does include “amendment of older LMPs” which almost all are, the FS would have to argue they are protecting eco integrity, conditions for at-risk species and carbon storage. And fire amendments (managed wildfires, prescribed burning, POD delineation and analysis of specific treatments) would do that, IMHO.