This is the town of Idyllwild (Inciweb had no photo links)

This is the town of Idyllwild (Inciweb had no photo links)

I thought, given our discussion here and elsewhere on the framing of the issue as “just move ’em out of the woods”, it was interesting to see, once again, exactly who and what is “in the woods.” Check out this article on the Idyllwild fire:

The communities of Idyllwild, Fern Valley and smaller surrounding communities in the mountains southwest of Palm Springs were under evacuation orders affecting some 2,200 homes and 6,000 residents and visitors, U.S. Forest Service spokeswoman Carol Jandrall.

People were being allowed home long enough to pick up essential items before evacuating as the flames crept over a peak just east of the towns, Jandrall said.

There were 4,100 residences threatened by the fire including homes, hotels, condominiums and cabins, Forest Service spokeswoman Melody Lardner said.

Coincidentally, there was this story on Southern Cal public radio.

I wonder if the Forest Service ever said the below specifically (new fire policy = function of climate change) or this was an interpretation..

Climate change is forcing the US Forest Service to rethink how it fights large wildfires. Global warming has increased the intensity of fires, forcing the USFS to spend more and more of its money fighting them. Now the agency has decided that it should be less aggressive in attacking big blazes, so long as they are not threatening property.

In 1991, the US Forest Service’s spent 13 percent of its budget on fire management. Today, because of climate change, that figure is more than 50 percent, officials say.

The change is visible at the top. Three years ago, the USFS added a chief climate advisor. Agency veteran Dave Cleaves holds the job; he’s been with the Forest Service for more than 20 years. He says forest managers used to consider global warming as a future problem, “but now we’re finding more and more it is an issue of the present and the future.”

Headwaters Economics, a Montana think tank, found that when the temperature is one degree warmer, fires burn on average three times as much terrain. Headwaters economist Roy Rasker said the cost of fighting larger fires could overwhelm local, state and even federal budgets.

The Forest Service already cuts underbrush and thins tree stands to minimize risks. But agency predictions of increasing fire intensity suggest that, even with these tactics, the amount of forestland vulnerable to burning will increase in the years to come, says U.S. Forest Service fire researcher Elizabeth Reinhart.

That reality is changing federal fire management. The Forest Service has been successful over the decades fighting fires with personnel-heavy attacks that aim to shut a blaze down right when it starts. Reinhart and other federal officials say sticking with that strategy is costly, and could overwhelm other necessary work in the forest.

“So in some cases, rather than direct aggressive suppression tactics, we’re able to monitor wildfires to stop its movement in one direction while letting it burn in another,” Reinhart says. “This sets up the landscape to be more resilient to the next wildfire.”

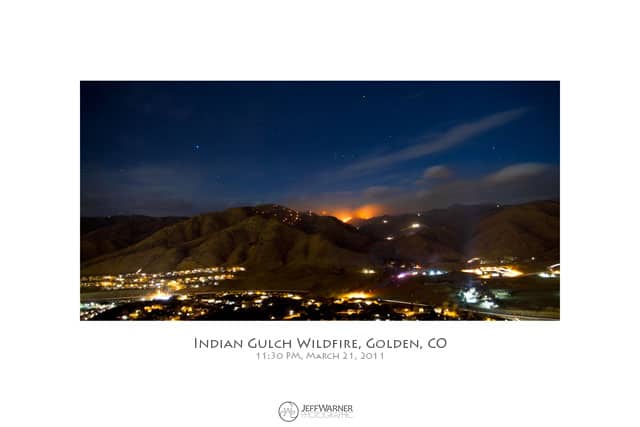

Picture supplied by Larry, below.