Jun 20: In the U.S. Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit, Case No. 08-17565.Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of California. The Appeals Court indicates that, “This court’s opinion filed on February 3, 2012, and reported at 668 F.3d 609 (9th Cir. 2012), is withdrawn, and is replaced by the attached Opinion and Dissent. . . The full court has been advised of the petition for rehearing en banc and no judge of the court has requested a vote onwhether to rehear the matter en banc. . . The petition for rehearing and the petition for rehearing en banc, filed on April 18, 2012, are denied.”

According to the Appeals Court, Plaintiff-Appellant Pacific Rivers Council (Pacific Rivers) brought suit in Federal district court challenging the 2004 Framework for the Sierra Nevada Mountains (the Sierras) as inconsistent with the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The Appeals Court said, “The gravamen of Pacific Rivers’ complaint is that the 2004 EIS does not sufficiently analyze the environmental consequences of the 2004 Framework for fish and amphibians.” On cross-motions for summary judgment, the district court granted summary judgment to the Forest Service.

The Appeals Court rules, “Pacific Rivers timely appealed the grant of summary judgment. For the reasons that follow, we conclude that the Forest Service’s analysis of fish in the 2004 EIS does not comply with NEPA. However, we conclude that the Forest Service’s analysis of amphibians does comply with NEPA. We therefore reverse in part, affirm in part, and remand to the district court.”In a lengthy dissenting opinion, one Justice concludes, “. . .the majority makes two fundamental errors: First, it reinvents the arbitrary and capricious standard of review, transforming it from an appropriately deferential standard to one freely allowing courts to substitute their judgments for that of the agency. . . Second, the majority ignores the tiering framework created by NEPA. Because the majority ignores such framework, it fails to differentiate between a site-specific environmental impact statement (EIS) and a programmatic EIS that focuses on high-level policy decisions. . .”

21st Century Problems

Summer Arrives With a Vengeance

Spring ends with wildfires making people homeless. After the fires are contained and controlled, does it really matter if ignitions were man-caused or the result of “nature”? Actually, there seems to be a “natural component” of human-caused wildfires. We should not be welcoming this “natural” and inescapable component.

This view from an abandoned fire lookout on the Toiyabe National Forest shows a decreased snowpack compared to a “normal” June. The Colorado fires were expected but, the “whatever happens” strategy has once again failed us humans. There are MANY things we could have done to reduce or eliminate this tragedy but, it seems that some people prefer shade over safety. The Forest Service seems willing to reduce detection services, to save a few pennies.

http://maps.google.com/maps?hl=en&ll=39.014782,-104.692841&spn=0.114038,0.264187&t=h&z=13

This view of the Black Forest area shows how very little fuels work was done prior to this year. News footage seems to show that homeowners preserved the trees all around them. The aerial view shows why people wanted to build their homes there. They love their shade! It IS unfortunate that so many people’s homes burned but, there is ignored reality working here.

Similarly, are we really prepared to accept whatever damage or loss to our forest ecosystems? We do know that there will be big wildfires this year, due to weather conditions. Are we willing to let “whatever happens” (including arson, stupidity, auto accidents and any other human ignitions) determine the state of our National Forests? Remember, there ARE people out there who will sue to stop fuels projects that sell merchantable trees.

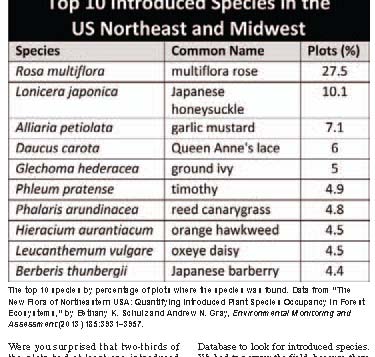

Introduced Species Found on Two-Thirds of FIA Plots in Northeast, Midwest

I think this is interesting; nice work by Steve Wilent in the Forestry Source so here goes:Introduced Species Forestry Source June 2013. Below is an excerpt.

I recently talked with Schulz to learn more about the inventories as well as her and Gray’s findings and what they tell us about introduced plant species. What follows is a portion of that conversation.

Were you surprised that two-thirds of the plots had at least one introduced species?

Yes, at first it was a big surprise. And then when we started looking at what species were coming out as introduced. When you’re dealing with thousands of plots and tens of thousands of species, you

need to go to a database to sort things out and find which species are introduced and which are native. We used the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Plants Database to look for introduced species.

We had to narrow the field, because there are many species that are natural in some areas and introduced in others. We tried to be conservative in determining which were the introduced species.

And there are many species that people aren’t aware are introduced, such as the grass timothy, which is easily recognized, and other benign species like common plantain. They are indeed introduced

species, but not every introduced species turns out to be a nasty ecosystem transformer.Many of the ones that do become transformers started off as introduced species, and sometimes they sit around in the environment for quite a while before something happens—some sort of disturbance—

that lets them start to gain ground and become more successful. It can be many years before they are recognized as being a species that may be of concern.

A couple of thoughts..I think she highlights that there are “bad” non-natives and “OK” non-natives. Non-natives are labelled “bad” for a reason. Which fits in with Lackey’s point in his paper here.

or example, in science, why is it that native species are almost always considered preferable to nonnative species? Nothing in science says one species is inherently better than another, that one species is inherently preferred, or that one species should be protected and another eradicated.

To illustrate, why do most people lament the sorry state of European honeybees in North America, a nonnative species that has outcompeted native bee species? Yes, our honeybees are nonnative, what many people would label as an invasive species, but people value their ecological role.

Conversely, zebra mussels, another common, but nonnative species are nearly universally regarded as a scourge. Where are the advocates of this species? Even with increased water clarity, no cheerleaders.

Or, what about North American feral horses — wild horses — mustangs! This is another nonnative species, but one that enjoys an exalted status by many. Would you want to be the land manager tasked with culling the ever-expanding population of this invasive, nonnative species?

Values drive these categorizations, not science.

But more pragmatically, there are many non-natives around. Any public money directed to their eradication (in my view) should be based on criteria including how “bad” they are specifically, to what; and (not inconsequentially) the likelihood of some kind of specific success.

Water, Climate Change, Thinning Trees and “Logging Without Use”

In the news clips this morning, I ran across this piece about Chief Tidwell’s recent testimony that:

America’s wildfire season lasts two months longer than it did 40 years ago and burns up twice as much land as it did in those earlier days because of the hotter, drier conditions produced by climate change, the country’s forest service chief told Congress on Tuesday.

“Hotter, drier, a longer fire season, and lot more homes that we have to deal with,” Tidwell told the Guardian following his appearance. “We are going to continue to have large wildfires.” …

Climate change was a key driver of those bigger, more explosive fires. Earlier snow-melt, higher temperatures and drought created optimum fire conditions. …

“This is a product of having a longer fire season, and having hotter, drier conditions so that the fuels dry out faster. So when we get a start that escapes initial attack, these fires become explosive in that they become so large so fast that it really limits our ability to do anything.” …

The above was from an article here (from the Guardian in the UK that also says Americans are increasingly building homes in “the wilderness”), that also says:

“It’s hard for the average member of the public to understand how things have changed,” Tidwell said.

“Ten years ago in New Mexico outside Los Alamos we had a fire get started. Over seven days, it burned 40,000 acres. In 2011, we had another fire. Las Conchas. It also burned 40,000 acres. It did it in 12 hours,” he went on.

Climate change was a key driver of those bigger, more explosive fires. Earlier snow-melt, higher temperatures and drought created optimum fire conditions.

Say it ain’t so, Tom.. tell us you were misquoted.

Really? In ten years we are seeing the difference? Due to climate change? Perhaps the weather was different between the two fires… or the status of the fuels.. or perhaps some fire suppression strategies were less effective.. Who is writing this stuff? Chief Tidwell is right… if quoted accurately..it is very hard for this member of the public to understand his points when they seem..not valid.

So I don’t understand the landscape of partisanship, but Hot Air appears to be a partisan blog. Nevertheless, they had a link to this article, which is of more interest. I looked up the authors and one had Yale F&ES credentials and the other D administration credentials.

I don’t know about the hydrology of it.. what I think is interesting is that the authors want to remove trees but kind of write off the timber industry as a way to do it.. because..

So how do we unlock the nexus to replenish the Earth? A century’s accumulation of dry fuel in public lands makes it too expensive and risky — for people, property, habitats or carbon emissions — to unleash prescribed fires throughout our 16-million-acre ponderosa tinderbox. Mechanical thinning generates popular distrust as long as timber industry chain saws try to cut “high grade” valuable mature growth to compensate for less profitable small-diameter “trash trees.”

Happily, a lumber mill’s trash has now become a water user’s treasure. Thirsty downstream interests could organize to restrict thinning to scrawny excess trees simply for the purpose of releasing the liquid assets they consume. Western water rights markets value an acre-foot at $450 to $650 and rising. So rather than compete with forests for rain and snow, private and public institutions could invest $1,000 per acre (average U.S. Forest Service price) to cut down fire-prone trash trees, yielding at least $1,100 to $1,500 worth of vital water. To reduce fuel loads and increase runoff, the water-fire nexus pays for itself.

It’s up to silviculture folks to say how many big trees need to go in a thinning. I don’t know why it’s OK to write off an entire industry who can help pay for this, and the authors seem to be assuming that all the trees that need to be thinned are “trash”. But as we see from Larry’s photos, in a stand of big trees, thinning smaller trees means that they are still big “enough” to be commercial. We could even call this attitude “logging without use” (remember “logging without laws”).. stands need thinning but using the trees is not good. Frankly, I just don’t get it.

Anyway, I think the op-ed is well worth reading in terms of making the case for treatment. I don’t know if their hydrologic statements are accurate, but I think it’s worth thinking about the idea that you could blame fire suppression, and dense stands and drought for some of the increase in fires, and not just climate change.

First, the past century of fire suppression has resulted in roughly 112 to 172 more trees per acre in high-elevation forests of the West. That’s a fivefold increase from the pre-settlement era.

Second, denser growth means that the thicker canopy of needles will intercept more rain and sSecond, denser growth means that the thicker canopy of needles will intercept more rain and snow, returning to the sky as vapor 20% to 30% of the moisture that had formerly soaked into the forest floor and fed tributaries as liquid. But let’s conservatively ignore potential vapor losses. Instead, assume that the lowest average daily sap flow rate is 70 liters per tree for an open forest acre of 112 new young trees. Even then, this over-forested acre transpires an additional 2.3 acre-feet of water per year, enough to meet the needs of four families.

Third, that pattern adds up. Applying low-end estimates to the more than 7.5 million acres of Sierra Nevada conifer forests suggests the water-fire nexus causes excess daily net water loss of 58 billion liters. So each year, post-fire afforestation means 17 million acre-feet of water can no longer seep in or trickle down from the Sierra to thirsty families, firms, farms or endangered fisheries.

SFI, FSC, CSA and LEED III

Yesterday I was out on an SAF field trip to Waldo Canyon..to look at the fire. Hope to get to share photos of that in the next few days. I would like to reiterate the question I posed in post II of this series…

Jay said:

In a state like WA or OR, you have to reforest after a regen harvest, but if you own 50,000+ acres and just cut 40% of your landbase over several years, how sustainable is that for local mills in the coming years (many now severed from a source of timber), ecological processes and organisms dependent on later seres or successional stages of forests? How is that sustainable for workers and communities when so many harvests were crammed into such a short period of time that labor/contractors had to be imported from outside of the community, only to leave when the cutting is done .

Now my read of any standard (SFI, CSA and FSC) is that cutting 40% of your landbase within several years would not meet the criteria. If we knew what company that was, maybe we could investigate how SFI treated it.

I am still curious and I think it might be interesting to run this one to ground.

Also, I tried to reply to Jason’s comment, but discovered that we had exhausted the number of comments. So here is his comment again and my reply.

Jason’s comment:

Superficially, SFI’s board mimics FSC’s 3 chamber system. From the SFI website:

“SFI Inc.’s 18-member multi-stakeholder Board of Directors comprises three chambers, representing environmental, economic and social interests equally… Board members include representatives of environmental, conservation, professional and academic groups, independent professional loggers, family forest owners, public officials, labor and the forest products industry”

http://www.sfiprogram.org/about-us/sfi-governance/sfi-board-members/

But look who is on their BoD in the environmental sector: The Conservation Fund, Bird Studies Canada, Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences, Ducks Unlimited Canada…not exactly a who’s who of the environmental community.

The social sector has two forestry academics, a state forester, a family forest owner and a guy from Habitat for Humanity Canada. Nothing wrong with that, but not notable for diversity or independence from the forest industry.

SFI appoints its directors from within. FSC’s BoD is elected in open elections by its membership — and membership in FSC is open to all. SFI has no membership.

Now to be fair, the conservation community has, by and large, spurned SFI, although there was a time when SFI tried reaching out to the major environmental groups to try to get them involved. Also, there was a period in the aughts when representatives from The Nature Conservancy and Conservation International served on the SFI BoD, which at that time was called the Sustainable Forestry Board or SFB. In the end, however, they left. I remember a key staffer from TNC saying that for a while they thought they could improve SFI from within sufficiently to justify their involvement, but that hope faded with time.

I think most of us hope that the forest certification wars won’t continue forever, and that at some point there will be some sort of rapprochement if not a merger. At the moment, though, that day seems a long way off.

I found Jason’s comment very interesting from a variety of perspectives. First of all, “the conservation groups listed are “not exactly a who’s who of the environmental community.””

1. Now, first of all, I think that we might all have our own roster of what environmental groups have the characteristics we prefer. It might be interesting for the folks on the blog to talk about their faves and why. There being a “who’s who” kind of implies that there is a generic feeling on the quality of environmental groups. I have read Bevington’s book on what some of the grassroots groups think of the big groups (not that the grassroots groups would like SFI any more than the bigs).

Now, I have been at the end of campaigns in which some of the groups said things which weren’t strictly speaking, true in my opinion. I acknowledge that culturally some groups throw things at an opponent, hoping some stick (that is how legal briefs are written). But do they really believe all the assertions? Do they go with the flow of their peers? Does the accuracy not matter in pursuit of “larger” goals?

As to the Sierra Club, I would be up for an open discussion with the public of certifying federal forests. I am not so much for behind the scenes working without giving the public the chance to talk about it ( a la NEPA-like process). If what I hear is true, of course.

2. It sounds as if some of the environmental groups may have withheld their support from SFI because they are aligned with FSC. I think we’re talking about chickens and eggs here. If these groups think they can do the best deal they can get with FSC, that’s fine. But then to say that it is a sign that SFI isn’t good enough because those groups don’t support it … SFI would have to allow even fewer things than FSC does, plus there would be even more drama.

3. I guess I am having a hard time with “The social sector has two forestry academics, a state forester, a family forest owner and a guy from Habitat for Humanity Canada. Nothing wrong with that, but not notable for diversity or independence from the forest industry.”

I guess I am having trouble with the idea that Habitat, forestry academics, and a state forester can’t be “diverse” or “independent from forest industry.” Jerry Franklin is a “forestry academic.” Most of the academics I know don’t get any money from the forest industry, so I don’t know what exactly you mean, unless it’s “growing up in an environment in which you know people who work for the forest industry.”

If I were TNC, I wouldn’t be on the SFI Board because the whole SFI vs. FSC thing generates more heat than light and TNC seems to be fairly good at prioritizing for practical conservation. Or the risks aren’t worth the rewards. Who knows? But it may or may not be based on any real problems with SFI as currently configured and managed.

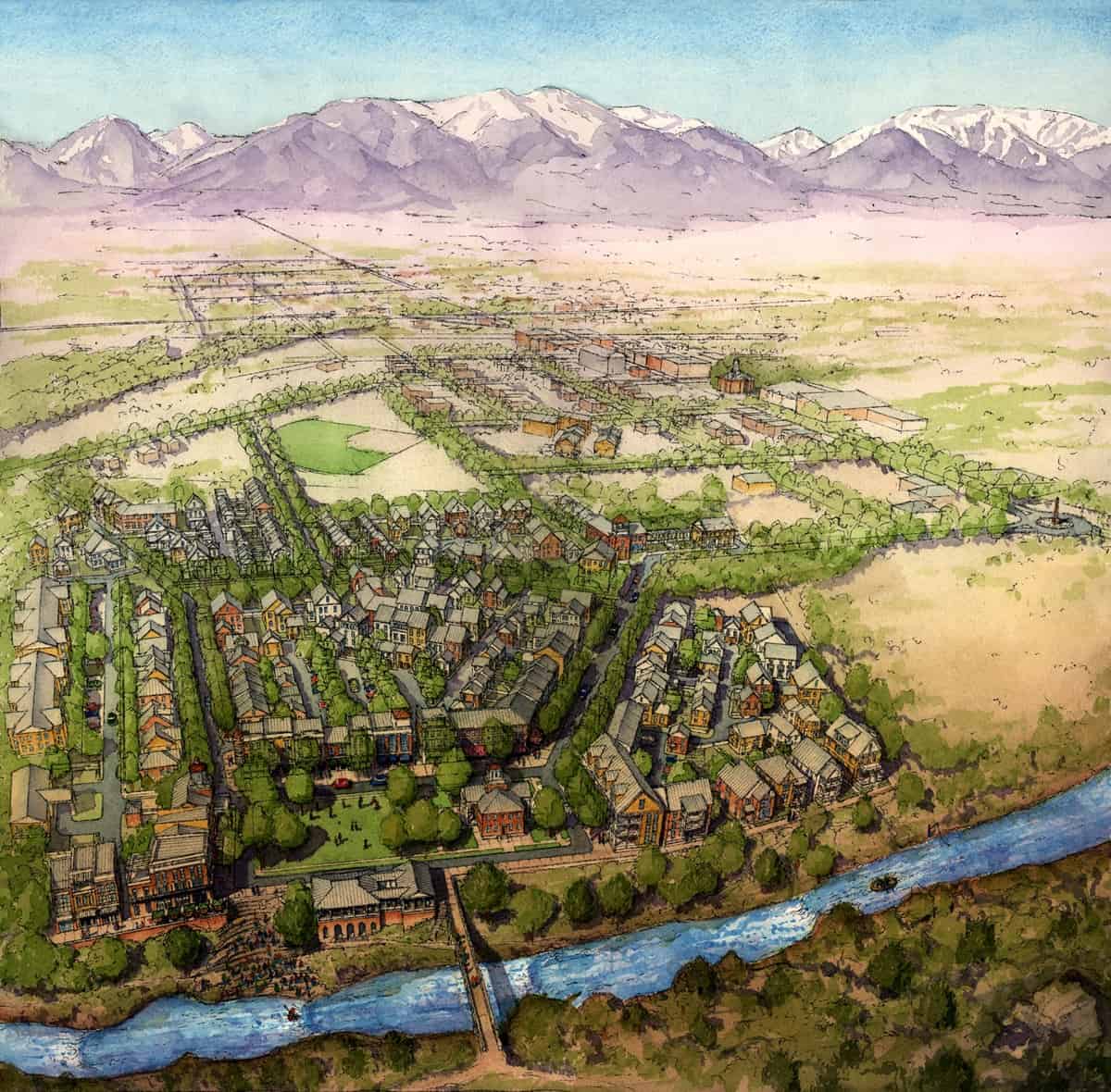

“Walkable” communities driving Western mountain housing market

Travis’s post reminds me of this story in the Denver Post business section a few weeks ago, which was deep in my pile of “to be posted.”

Here’s the link to the Post story.

Here’s an excerpt:

BUENA VISTA — Homes within walking distance to shops and restaurants are forecast to drive the housing markets and economies in mountain communities of the interior West as the recession’s effects wane.

That’s according to a recent study of high-country housing trends over the past decade by the Sonoran Institute, a nonprofit public-policy group that advocates for better management of growth in the West. The group’s 60-page study — “Reset, Assessing Future Housing Markets in the Rocky Mountain West” — shows that while homebuyers are willing to pay an average of 18.5 percent more for a house in a walkable mountain neighborhood in the Rocky Mountain West, the supply of homes in or near downtown commercial areas is too small.

“There is growing demand for walkable neighborhoods, and it’s an untapped market opportunity,” said Clark Anderson, director of the Sonoran Institute’s Western Colorado Program.

Looking at homebuying trends in six Western mountain communities from 2000 to 2010, including Eagle, Buena Vista and Carbondale, the group identified a number of trends driving demand for what it called “compact walkable neighborhoods.”

Younger residents are entering the homebuying market and able to work remotely from hamlets formerly occupied by agricultural or service-sector workers. Older people are retiring in the hills and often downsizing. Household incomes are getting smaller and so are household sizes. Limited land supply in recreational mountain valleys is fueling buyer and municipal interest in denser housing projects.

“These are trends that are happening in small communities, large communities, resorts, towns and cities across the Rocky Mountains. Consumer preferences and choices are creating a different-looking housing market from what we have known in the past,” Anderson said.

The Womb of Time: Bill Cronon, Teddy Roosevelt and a Sustainable American Future

The following is a guest post by Travis Mason-Bushman

During the first week of my tenure as an impressionable Student Conservation Association intern in the R10 Regional Office’s cube farm back in fall 2010, I was subjected to a mandatory screening of The Greatest Good, the Forest Service’s centennial documentary. In that film lies one of the reasons I ultimately chose to pursue a career with the agency – the summative words of William Cronon:

The work of the Forest Service can and should and must continue into the 21st century and beyond. Because in a way, the issues that this agency has been struggling with since its creation are at the very core of what it means to be a human being on the planet and what it means to build a sustainable human society. And it is the struggle, not just of the United States. It’s the struggle of humanity.

Maybe sappy – check that, combined with the rousing music and soaring visuals, definitely sappy. And yet Cronon’s words rang true. As Jack Ward Thomas noted earlier in the film, we are a species on this planet and like every species, we have to exploit our habitat to survive. We cannot have zero impact on the land. Sarah Gilman is right to point out the hypocrisy trap of NIMBYism, which has too often loomed in the background of environmental debates – “as long as you don’t drill next to my house, I don’t care.” Arguments that we shouldn’t log a single stick from the national forests run headlong into the fact that we do need lumber, we do use paper, we must utilize trees – and if we don’t produce what we use and instead export our environmental damage elsewhere, it is little but NIMBYism writ large. There is and must be a place for sensible, sensitive resource production.

But I was struck by the angry, dismissive responses to Matthew Koehler’s comment that “I, for one, don’t continue to insist on Americans continuing to live as we do now,” as if it is somehow an American birthright to profligately use and abuse the planet’s finite resources far out of proportion to our numbers. This is the true entitlement crisis: the belief that we are entitled to exploit and use up every resource we can possibly get our hands on or our drilling rigs into.

A growing number of Americans, and particularly those of my generation, are recognizing that what modern humans have been doing – “our way of life” – is entirely unsustainable. There is not oil enough on this planet, forest enough on this planet, carbon capacity enough on this planet, for humans to live exactly the way we lived for the last 100 years for the next 100 years. Infinite growth on a finite planet is, quite simply, impossible.

Does that mean we have to go back to the Stone Age? I don’t think so. But does that mean we might rethink decisions about our way of life that were made in the last 50-100 years, often without a full understanding of their impact on ecology and resources? Does that mean we should perhaps reconsider what we need and what we want? Does that mean we ought to view our activities as a species through a much longer frame of perspective? Yes, yes, and yes. (A rare acceptable use of the Oxford comma.)

As I have been fond of pointing out in interpretive talks at the Tongass National Forest’s rapidly-retreating Mendenhall Glacier – perhaps the Forest Service’s single most frying-pan-in-the-face obvious example of climate change – I don’t own a car. In fact, I’ve never even possessed a driver’s license. I biked to work every day, rain or shine (and if you know the Tongass, it was mostly the former.) That has been a conscious decision, that I will be one less internal combustion engine on the roads of the United States. And I am far from alone – studies have shown, time after time, that Millennials are driving 20% less than our parents did at similar ages. Cost, convenience, environmental sensibilities, culture – for all those reasons and more, my generation is car-sharing, using transit, walking, biking and generally using any number of forms of transportation that are far more energy-efficient and less carbon-dependent. We support high-speed rail, view climate change as a real threat and are eschewing suburban sprawl that has consumed precious land and energy.

Will these changes alone solve our collective human challenge? Of course not. But they are, unmistakably, a sign that my generation recognizes that challenge – the challenge of adapting a way of life left to us by a generation apparently unwilling to confront the limits of geology and ecology that we are rapidly approaching. We must be wise stewards of our natural resources, because these are all we have or will ever get. We must have concern for the planet’s ecosystem, because there is but one in the universe.

And yet this view of a planet with limits, a civilization built for the long run, is hardly new and ought not be controversial. After all, it found one of its most eloquent defenses nearly 100 years ago from one of the men responsible for creating the Forest Service in the first place:

The “greatest good for the greatest number” applies to the number within the womb of time, compared to which those now alive form but an insignificant fraction. Our duty to the whole, including the unborn generations, bids us restrain an unprincipled present-day minority from wasting the heritage of these unborn generations.

That man, of course, was Theodore Roosevelt. And it is to his view of the “greatest good” which I believe our future society must adhere – one that considers most important not profitability next quarter or GDP growth next year, but the ecosystem’s next decade and the climate of the next century.

Travis is a Tongass National Forest SCEP trainee/Pathways intern/whatever they’re calling us this week, and worked for the last two summers as a ranger-interpreter at the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center. He just completed a master’s degree in recreation at Indiana University, with his thesis being a study of visitor experiences and interpretive outcomes at Mendenhall Glacier Recreation Area.

Forest Red Zone Report.. Link to Bob Berwyn Post

Bob Berwyn has a nice post on the new Red Zone Report.

Here is a link to his post.

Below is an excerpt.

Here is a link to the report. It is a GTR from the Rocky Mountain Research Station.

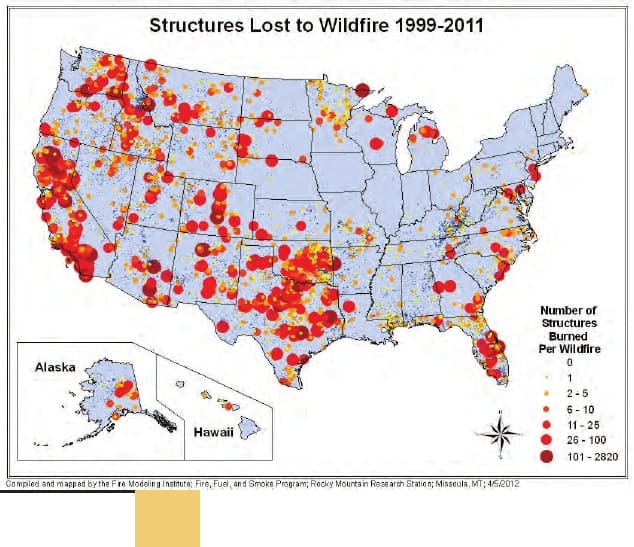

According to the report, about 32 percent of U.S. housing units and 10 percent of all land with housing are the wildland-urban interface. The growth of residential zones around fire-prone forests has resulted in huge budget challenges for the Forest Service. Between 2001 and 2010, fire suppression costs doubled to about $1.2 billion. Read the full report here.

Other costs include restoration, lost tax and business revenues, property damage and costs to human health and lives. As and example, the report cites the 1996 Buffalo Creek Fire, which resulted in more than $2 million in flood damage and $20 million in damage to Denver Water’s supply system.

From the report:

In 2000, nearly a third of U.S. homes (37 million) were located in the WUI.

More than two-thirds of all land in Connecticut is identified as WUI.

California has more homes in WUI than any other State—3.8 million.

Between 1990 and 2000, more than 1 million homes were added to WUI in California, Oregon, and Washington combined.

WUI is especially prevalent in areas with natural amenities, such as the northern Great Lakes, the Missouri Ozarks, and northern Georgia.

In the Rocky Mountains and the Southwest, virtually every urban area has a large ring of WUI, as a result of persistent population growth in the region that has generated medium and low-density housing in low- elevation forested areas.“The Wildfire, Wildlands and People report reminds us that people can and should take steps to protect their homes from wildfires,” said U.S. Forest Service Chief Tom Tidwell. “Communities with robust wildfire prevention programs are likely to have fewer human-caused wildfires. In addition, fire intensity is dramatically reduced in areas where restoration work has occurred.”

Between 2006 and 2011, some 600 assessments were completed on wildfires that burned into areas where restoration work had taken place. In most of these cases, fire intensity was reduced dramatically in treated areas. Residents can reduce excess vegetation within and around a community to reduce the intensity and growth of future fires and create a relatively safe place for firefighters to work to contain a wildfire, should one occur.

If not at Maroon Bells, Then Where? Or Predicting Poopy Trailheads

s

As I go about my outdoor recreation, I go to Jefferson County Open Space (free bathrooms). when it gets warmer I go up to the local State Park ($7 per day or Park Pass for $70 a year). When it gets hotter, I may have to go to Brainerd Lake (host program, mildly ratty,pay to enter the site on National Forest) or to Rocky Mountain National Park (first class, good bathrooms but no dogs).

I’ve been to the Bells many times with out of town guests. Like Mt. Evans, I’ve never heard “we shouldn’t pay ” from folks. Both places have a nice (not second-class recreation) feel to them. I bet many folks (social scientists, want to do a survey?) don’t even know they’re in a National Forest and not a National Park.

And if it was a National Park, we would probably pay more, but not be able to take our dogs..less desirable on both counts.

But this bathroom stuff is quite silly, in my opinion. See this article from the Aspen Times

Benzar and the Forest Service have different interpretations about the application of the fee at Maroon Lake, 10 miles southwest of Aspen. The No-Fee Coalition contends that those who want to hike Buckskin Pass or West Maroon Pass and want to park a vehicle at Maroon Lake shouldn’t have to pay the $10 fee if they have no intention of hitting the bathroom before they hit the trail. Likewise, sightseers in cars shouldn’t have to pay the fee if they don’t use the bathroom or other facilities at any of the six developed recreation sites, she said.

Here’s the deal to me..yes, folks could install “pay to poop” card readers at the outhouses, but that contributes to the Forest Service “ratty second-class recreation” vibe. Not to speak of all the folks who won’t pay $10 and leave the nearby forest looking and smelling like a giant outhouse (not to speak of the ecosystem integrity when all that extra nitrogen is applied!)

Which is part of the reason people want to transfer FS land to the Park Service- because somehow the Parkies appear to not allow rattiness. It seems like that is the obvious trail we’re going down, any area with lots of folks gets transferred because then there can be money to take care of them. Try “I am just driving through and not using Park facilities” at a National Park.

Since we’re all about following the law, and the recreation fee legislation is up before Congress, let’s see how many different ideas there are about alterations to the legislation to make it more common-sensical.

Here are some other excerpts from the story:

Officials at the Aspen Ranger District and the White River National Forest Supervisor’s Office have countered over the years that collecting the fee is vital to operating the necessary facilities at Maroon Lake. Without the fee, the Maroon Bells would soak up all the recreation funds available through the regular budget process. Instead, funds collected don’t go back to the treasury. They are used at Maroon Bells for operations and maintenance.

The Forest Service and the predecessor to the Roaring Fork Transportation Authority started bus service to the Maroon Bells 35 years ago. The federal agency also worked with Pitkin County to limit traffic on Maroon Creek Road, a county route. When the fee was adopted formally through federal legislation, cyclists fought the Forest Service for an exemption. Bikes and pedestrians get free passage past the entrance station.

The federal agency’s total collection from Maroon Valley visitors was $231,364 last year. That is a 50 percent increase from the collections in 2008, according to Forest Service figures.

Without the fee, Maroon Creek Road would be overwhelmed with traffic and the agency wouldn’t have adequate funds for operations, officials have said.

“Having that fee collection keeps it world-class,” said Martha Moran, a longtime veteran of the Aspen-Sopris Ranger District who helps oversee recreation programs. “If you want trash picked up and toilets cleaned, you can’t use volunteers.”

Maybe with the current legislation, this recreation is “unsustainable” based on the planning directives definition of within budget. I wonder what Aspen folks would think of the FS shutting it down when their plan is revised?

Tongass Futures Roundtable Collaborative Group Shutting Down

Thank you to David Bebee for passing along this news report by Ed Schoenfeld, CoastAlaska News. The Tongass Futures Roundtable has been discussed here on this blog a number of times in regards to the management of the Tongass, America’s largest National Forest.

Thank you to David Bebee for passing along this news report by Ed Schoenfeld, CoastAlaska News. The Tongass Futures Roundtable has been discussed here on this blog a number of times in regards to the management of the Tongass, America’s largest National Forest.

The Tongass Futures Roundtable is shutting down. The organization tried to resolve Southeast Alaska forest-issue conflicts. It formed about seven years ago.

Organizers hoped to bring together all parties involved in the forest to craft compromises on land-use issues, such as logging and habitat protection.

“The roundtable brought people together who had never had to sit across from each other at a table. The normal environment was a courtroom,” says Bruce Botelho, the group’s facilitator and moderator.

The former attorney general and Juneau mayor says roundtable members decided to end their work during a meeting earlier this month.

“One of the benefits for us to dissolve right now is to create the opportunity for people to come together and perhaps learn from our experience, but also build on it. And one would hope that any assembly of stakeholders would truly bring back the whole range of participants,” he says.

Membership originally included industry, government, tribal and environmental leaders. But about two years ago, the state, timber representatives, four towns and some conservation groups pulled out.

“We didn’t have enough movement in the direction we felt needed to occur,” says State Forester Chris Maisch, one of the original roundtable members.

“So the governor decided it would be best to put state energy and time and resources into a task force, which he established through an administration order,” he says.

Maisch chaired that task force, which released its final report a few months ago.

It recommended a number of actions meant to increase logging. One was expanding state forests. Another was revising state rules to help small timber operators.

Yet another called for the federal government to turn two million acres of the Tongass over to the state to be managed for harvest.

Maisch says the timber task force has since shut down.

Botelho says the roundtable eventually decided it couldn’t fully do its work without the groups that left. It will cease operations July 1st. But he says it achieved some of its goals.

“We devoted a great deal of time to examining the proposed mental health land exchange between the state and the trust and ended up endorsing a process, which is underway. And I think that, absent the support of the roundtable, would have been more difficult,” Botelho says.

He says some of the roundtable’s working groups will also continue meeting. One focuses on Alaska Native issues, another on sustainable forests.

The Tongass Futures Roundtable had about 35 members and tried to reach decisions by consensus. State Forester Maisch says that just didn’t work.

“It was a well-intentioned effort. And a lot of people spent a lot of time in trying to make that process work. And unfortunately, it just wasn’t the right time and the right place. So it’s too bad that it didn’t come to a better conclusion,” he says.

The roundtable had funding support from the Rasmuson Foundation and other donors. The Juneau office of the Nature Conservancy, an international conservation organization, staffed the group.

Roundtable Coordinator Norm Cohen says money was not the reason the group decided to dissolve.