Colorado’s plan to reintroduce lynx to the southern Rocky Mountains became one of our greatest challenges. At first, many Coloradans were angry about the plan, which came in response to the Fish and Wildlife Service listing the lynx as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. But after dozens of meetings and hundreds of letters, emails, and calls to the department, governor’s office, and the state legislature, an extraordinary picture emerged. None of the complaints were about the lynx. Many opposed the lynx reintroduction plan, but not one single message contained any complaint about the animal itself. The concerns were instead about the federal land management policies that accompany endangered species listings.

Colorado’s lynx recovery program represented a state-led effort to carry out the original intent of the Endangered Species Act: to recover species that we might otherwise lose. In the case of the lynx, those fears were understandable. The U.S. Forest Service had ordered all national forests in Colorado to rewrite their management plans based on potential habitat for lynx, even though there were none in the state. All land managers, communities, and other stakeholders affected by the listing had to determine what it, as well as the Forest Service’s order, meant to them. Discussions often centered on whether to close roads and trails, ban snowmobiles and off-road vehicles, discontinue logging and mining, stop oil and gas exploration, close campgrounds, limit ski area expansions, or eliminate grazing. In short, the debate was about everything but the lynx.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has always insisted that Colorado is not prime lynx habitat. Lynx had rarely been seen there. The last one was trapped in 1973, and only 18 had ever been documented in the history of the state. Yet the Forest Service remained determined to include lynx recovery as a key component of its management plans in the state. From the state’s perspective, the only clear answer was to establish a thriving population. So we did just that. Between 1999 and 2006, we imported 218 lynx to Colorado from Canada and Alaska, outfitted them with satellite collars, and studied their behavior. Today, their population is thriving and self-sustaining in the state and, along the way, has disproved many of the Forest Service’s initial assumptions about the species.

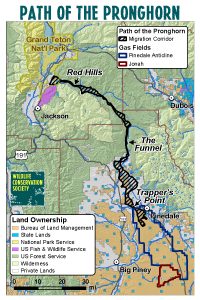

Federal documents said the San Juan Mountains were the southernmost limit where lynx could live, yet several migrated farther south, even into New Mexico. Forest Service officials said the lynx ate only snowshoe hares, yet Colorado lynx have eaten a much more varied diet, including squirrels, prairie dogs, and birds. One died from plague after eating a diseased prairie dog; one ate a dog in Durango. Some officials claimed lynx were threatened by ski areas, yet at least one was monitored living in a ski area during the crowded winter season.

The Forest Service also maintained that lynx would not cross open areas greater than 100 yards. Yet several lynx introduced in southwest Colorado crossed enormous areas of wide-open spaces on lengthy migration routes. One was trailed to Nebraska, several through the San Luis Valley, and still others beyond Interstate 70 more than 200 miles north of their release. In 2007, one lynx crossed five counties into Kansas before being recaptured south of Wakeeney, some 375 miles across the Great Plains. Others have roamed north as far as Montana. But the ultimate traveler was a lynx that, after four years in Colorado, headed home to Canada, 1,200 miles from his release site in Mineral County.

Colorado’s success with its lynx recovery program is instructive because it represented a state-led effort to carry out the original intent of the Endangered Species Act: recover species that we might otherwise lose. Like hundreds of other listed species, lynx were not threatened simply because of habitat loss; they live primarily at high altitudes where there are no towns and little other human activity. They were threatened largely because they have beautiful fur, and for many years our ancestors trapped them for it. For a time, the government tried to blame the species’ decline on shrinking snowshoe hare populations caused by timber harvest, fire suppression, and climate change. But in reality, as we discovered in Colorado, the high Rocky Mountain habitat remains mostly intact, so reintroducing the lynx was the simple answer, and it worked.

Despite its proposed land-use restrictions to benefit the lynx, the federal government had no plans to establish any lynx populations in the state. In fact, is it unlikely that the federal system would ever have done anything to recover the lynx. The Endangered Species Act focuses almost exclusively on regulating habitat, not on recovery. That’s precisely why state leadership is essential.