The U. S. Supreme Court has issued its decision in United States Fish and Wildlife Service. v. Sierra Club (March 4, 2021), the Freedom of Information Act case we have discussed previously. The EPA changed its proposal for cooling water intake structures at power plants after receiving a draft biological opinion from the consulting agencies that found the proposal would jeopardize listed species. In a 7-2 decision, the Court reversed the lower court decisions and held that a draft biological opinion on the effects of the original proposal, which was shared informally between the EPA and the consulting agencies, was exempt from disclosure under FOIA as a predecisional and deliberative document. Specifically, “the determinative fact is not their level of polish—it is that the decisionmakers at the Services neither approved the drafts nor sent them to the EPA.” This shows that the consulting agencies did not “treat them as final,” which is consistent with the context of the consultation regulations.

The ESA consultation process makes this case more confusing than it needs to be. Normally, drafts circulated among members of a government team would qualify as deliberative, but here the team is comprised of multiple agencies following prescribed interagency consultation procedures. A “draft” biological opinion is specifically identified by consultation regulations, and it must be provided by the consulting agencies if requested by the action agency. In this case, the draft was provided by consulting agency staff without official signatures. Without those signatures, it was not the final position of the consulting agencies, even though it had the effect of EPA changing its proposal. With those signatures, apparently a draft biological opinion would have been “final” for the purpose of FOIA, and should have been disclosed. (This may or may not have been the result of good lawyering, but it would be good lawyering to so advise in the future.)

The Court doesn’t dig into the other aspects of this FOIA exemption, one of which is that factual material is not deliberative and must be released, or therefore the question I raised about the need to disclose the science on which the deliberations were based. Apparently, that would happen here on a remand to determine what is “segregable” non-exempt material. I wonder whether the scientific conclusions about the effects of the original EPA proposal are also considered deliberative because they were not yet “officially approved.”

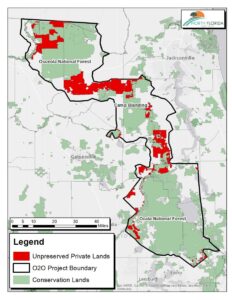

A more typical case, which does address this question, is this new one from the D. C. District Court involving Florida Key deer and its Species Status Assessment (Sierra Club v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Feb. 26. 2021).

On its face, a factual scientific report, produced “independently from any” regulatory or policy decisions, see FWS Letter Describing SSA, does not qualify as deliberative… Nothing in this description indicates that the report contains “advisory opinions, recommendations[, or] deliberations” regarding the agency process at issue.

Yet, while the privilege does not generally extend to mere factual recitations, (citation omitted) “the D.C. Circuit has cautioned against overuse of the factual/deliberative distinction.” Such hesitation stems from the recognition that the drafter’s selection of facts can itself reveal the decisionmaking process.

This case also addresses the need for agencies to demonstrate harm to their deliberative process that would result from disclosing these records, which the Supreme Court does not address in the EPA case. Public response to the case, including suggestions for congressional action, is discussed here. (This article includes a picture of the the power plant at issue.)