Many interesting things about this paper.. (no paywall, yay!) but the fact that effects at different scales can be different and that real world phenomena may not be detectable at larger scales. So a danger if “the science” is only done at a larger scale. People and organisms tend to live at the local scale or landscape,, so one would imagine impacts at that scale are most important to study. So at least studies should be conscious (and explain in the text?) of their choice of scales, and relevance to the topic and local people and environment. Otherwise it may not only discount local observations and experiences, but give a veneer of “science” to those scale-dependent views.

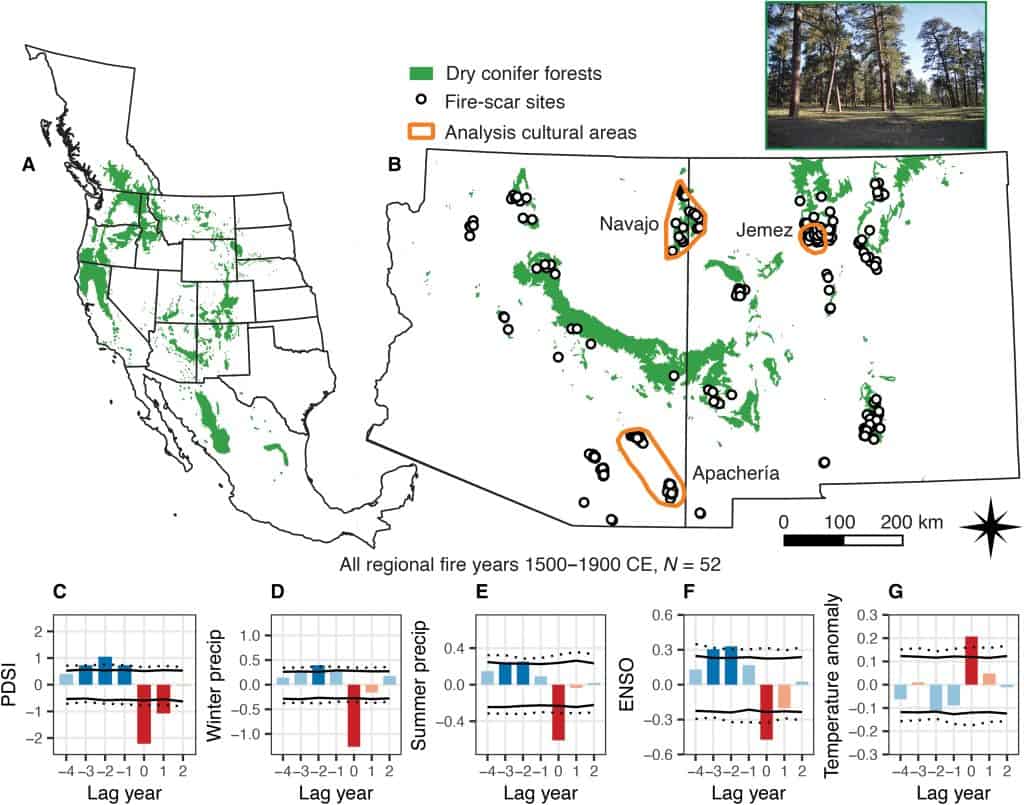

At the landscape scale, drought remained a potent driver of fire activity even during intensive use, suggesting that even in heterogeneous fuelscapes created by Indigenous patch burning, climate could overcome limitations in fuel continuity and promote spreading fires. These observations corroborate prior research that Indigenous patch burning can buffer—but not entirely eliminate—local- to landscape-scale climate influences on widespread fire activity (10). We show that this effect is scale dependent. Locally, the buffering of climate influences was strongest. At the landscape scale, climate impacts were moderated, but drought persisted as an important influence on fire activity. At the regional scale, the canonical climate pattern continued to be the primary driver of fire activity through time. The repetition of this cross-scale variation in fire-climate drivers across all cultural regions and periods hints at a common cause—human impacts on fire regimes were scale dependent, in space and time (13). This scale dependency means that paleofire records composited and assessed at regional scales can mask important, localized Indigenous influences on fire activity and the ecological and social influences of this management (13).

Here are the management implications:

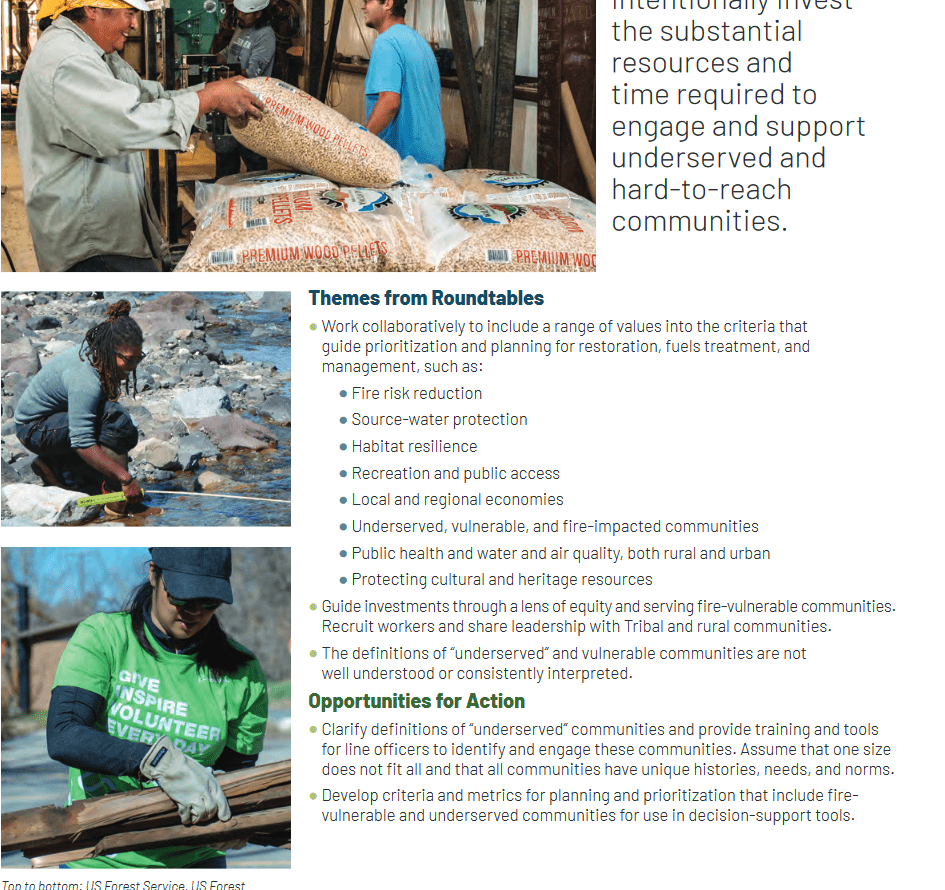

These results also have implications for modern fire management and policy. In the wake of recent wildfire disasters—fires that damages homes, infrastructure, water sources, and kill humans—there have been calls to restore traditional Indigenous burning practices in western North America (7, 65) and elsewhere (66). Indigenous-managed pyrodiversity offers the opportunity to reduce fire hazard (6), support fire-sensitive plant and animal species (8), reduce carbon emissions (67), and empower Indigenous people (7, 65, 68). Our results show that a further benefit of supporting, restoring, or emulating Indigenous burning practices, including modern prescribed burning efforts, would be the buffering of the impact of increasing fuel aridity on fire activity. To achieve landscape and regional scale fire-climate buffering, however, these applied burning practices would need to be conducted often and at the scales of interest or in strategic locations that have particularly important influence on landscape-scale fire behavior (69). Land managers have struggled to accomplish this goal (70), but future management aims for increasing prescribed burning by more than an order of magnitude (56, 71). As was the case in recent centuries, climate will continue to play a strong role in influencing fire activity even in the best-case management scenarios. However, Indigenous burning, prescribed burning, and managed wildfire at the appropriate scales (7, 65) can all contribute to undermine climate as a “force multiplier” in our wildfire challenges as we endeavor to get more “good fire” on the ground (22, 72).