Are we headed for an abstraction knock-down with the 2012 Planning Rule requiring managing National Forests for “ecological integrity” and states like California promoting “resilience”? I bolded the FS goals below. Note that with regard to PB, CALFIRE, among other things, will “increase support for workforce development and training programs, and evaluate options to address liability issues for private landowners seeking to conduct prescribed burns for the private insurance market.” I just posted the summary below, so there may be other FS contributions in the main document.

****************************************

In January the State of California came out with:

The Wildfire and Forest Resilience Action Plan is designed to strategically accelerate efforts to:

» Restore the health and resilience of California forests, grasslands and natural places;

» Improve the fire safety of our communities; and

» Sustain the economic vitality of rural forested areas.

To meet these goals, the following will need to be achieved:

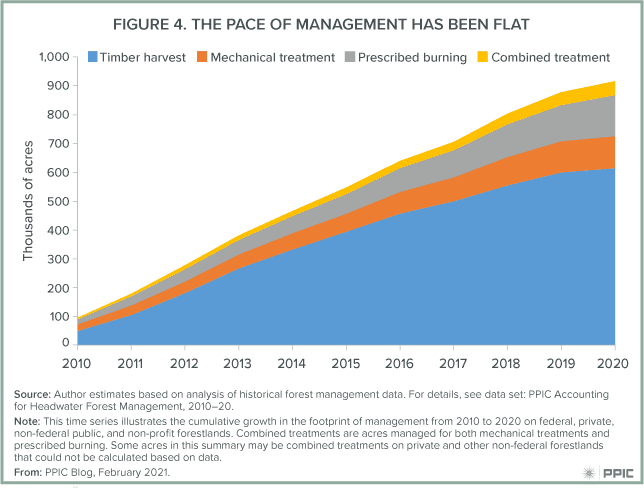

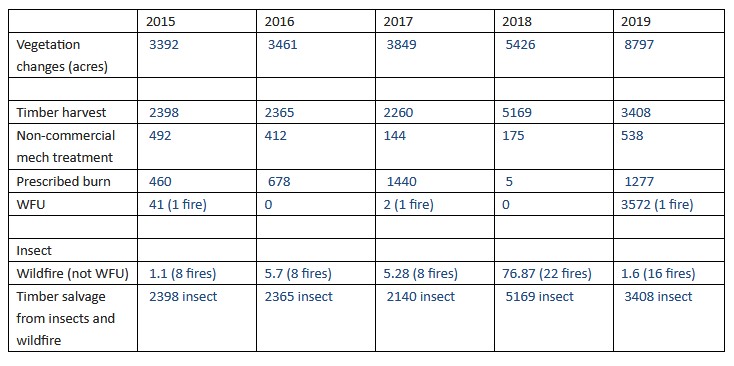

Scale-up forest management to meet the state and federal 1 million-acre annual restoration target by 2025.

» The Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) and other state entities will expand its fuels management crews, grant programs, and partnerships to scale up fuel treatments to 500,000 acres annually by 2025;

» California state agencies will lead by example by expanding forest management on state-owned lands to improve resilience against wildfires and other impacts of climate change; and

» The USFS will double its current forest treatment levels from 250,000 acres to 500,000 acres annually by 2025.

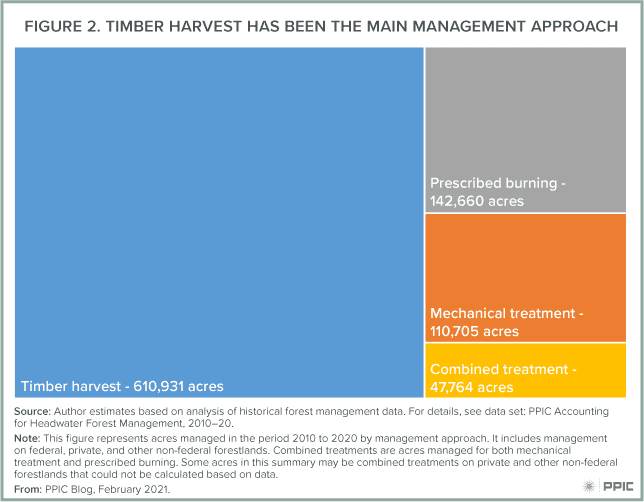

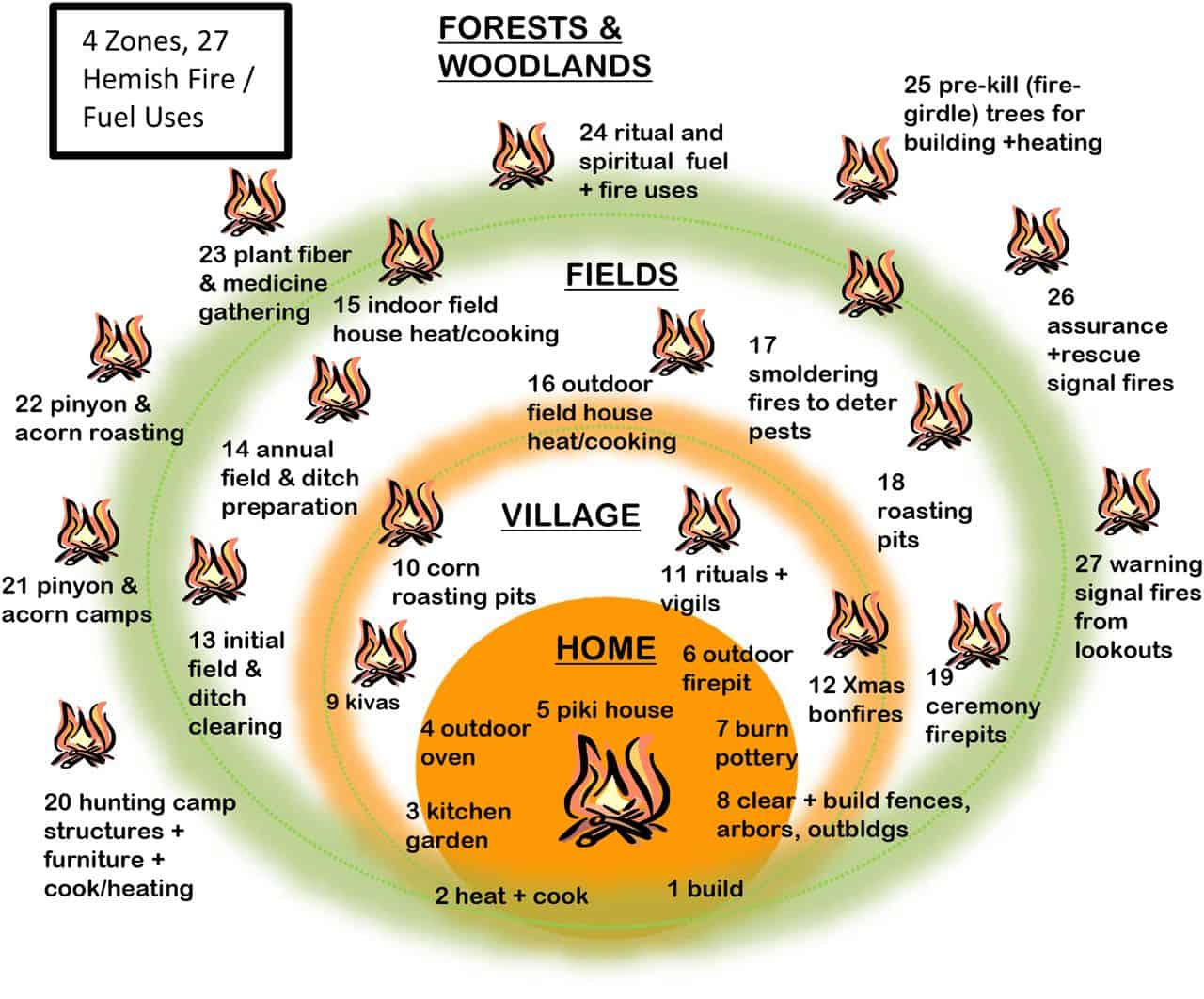

Significantly expand the use of prescribed fire across the state:

» CAL FIRE will expand its fuels reduction and prescribed fire programs to treat up to 100,000 acres by 2025, and the California Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks) and other state agencies will also increase the use of prescribed fire on high-risk state lands;

» The USFS, in partnership with CAL FIRE, tribal governments, and other agencies will seek to establish a Prescribed Fire Training Center to provide training opportunities for prescribed burn practitioners and focus training efforts on western ecosystems;

» CAL FIRE will also establish a new tribal grants program, increase support for workforce development and training programs, and evaluate options to address liability issues for private landowners seeking to conduct prescribed burns.” for the private insurance market;

» The USFS will significantly expand its prescribed fire program to attain its 500,000-acre target for forest treatments by 2025.

Reforest areas burned by catastrophic fire:

» The USFS will develop a restoration strategy for wildfire impacted federal lands and CAL FIRE will partner with the California Office 6 January 2021 of Emergency Services (Cal OES) and other federal, state, and local agencies to develop a coordinated strategy to prioritize and rehabilitate burned areas and affected communities. These ecologically-based strategies will focus on silvicultural practices that increase carbon storage, protect biodiversity, and build climate resilience.

Support communities, neighborhoods, and residents in increasing their resilience to wildfire:

» CAL FIRE will significantly expand its defensible space and home hardening programs and launch a new program building upon the Governor’s 35 Emergency Fuel Break Projects by developing a list of 500 high priority fuel breaks across the state. This list will be continuously updated.

» The California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) will expand its Regional Forest and Fire Capacity (RFFC) Program to all high-risk areas throughout the state and increase local and regional governments’ capacity to build and maintain a pipeline of forest health and fire prevention projects.

Develop a comprehensive program to assist private forest landowners, who own more than 40 percent of the state’s forested lands:

» CAL FIRE will coordinate the implementation of several grants and technical assistance programs for private landowners through a unified Wildfire Resilience and Forestry Assistance Program.

Create economic opportunities for the use of forest materials that store carbon, reduce emissions, and contribute to sustainable local economies.

» The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) is leading the development of a comprehensive framework to expand the wood products market in California and will partner with CAL FIRE, the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GoBiz), the USFS, and the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank (iBank) to draft a market development roadmap and catalyze private investment into this sector.

Improve and align forest management regulations:

» The Board of Forestry and Fire Protection (BOF) is leading the expansion of a new online permitting tool and permit synchronization initiative to provide a one-stop shop for permits from several agencies and will use the California Vegetation Treatment Program (CalVTP) to streamline project planning and environmental review.

Spur innovation and better measure progress:

» CAL FIRE and the USFS, in coordination with the USDA California Climate Hub, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), and other agencies, will seek to establish a Forest Data Hub to coordinate and integrate federal, state, and local reporting on forest management and carbon accounting programs, and serve as a clearinghouse for new and emerging technologies and data platforms.

This strategy will also be integrated into the state’s efforts to combat climate change through the following actions:

1. Scale-up forest thinning and prescribed fire efforts to reduce long-term greenhouse gas emissions and harmful air pollution from large and catastrophic wildfires;

2. Integrate science-based climate adaptation and resiliency strategies into the emerging state-wide network of regional forest and community fire resilience plans;

3. Drive forest management, conservation, reforestation and wood utilization strategies that stabilize and increase the carbon stored in forests while preserving biodiversity and revitalizing rural communities;

4. Improve electricity grid resilience; and

5. Promote sustainable land use.